Mr Gray succeeded Edward Tallent as medical officer to the workhouse in July 1851.

His birthplace given in the censuses is alleged to be in Devon in a parish called Maker or Nakes. A Family search transcribed record, however, leads to the baptism in Maker, Cornwall,[1] on 5 June 1803 of Thomas Nathaniel Gray, born on 27 December 1793, the son of Thomas and Jenny. He was aged 9 at the time, which is consistent with his age on death and in the censuses.

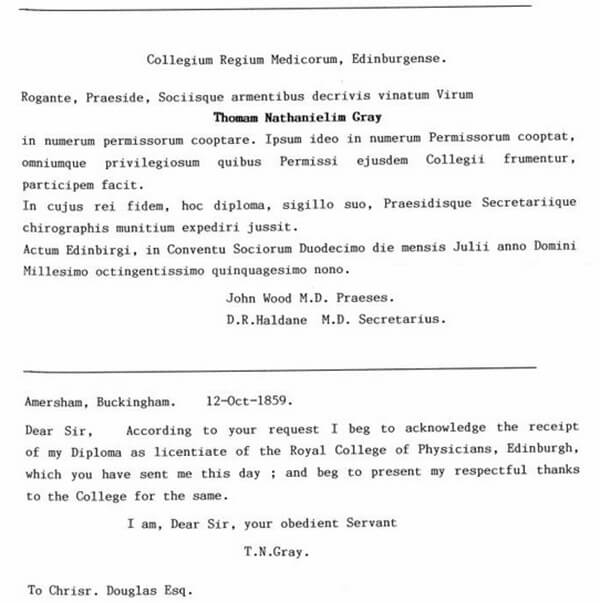

He became a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries in 1816 and an MRCS the following year according to the 1859 Medical Directory. He added to this LRCP Edinburgh 1859 and this appeared in the Directories of 1860 and 1863. The entry is expanded in 1860 by stating that he had been Apothecary at St George’s Hospital and was an Honorary Member of the Medical Society of London.

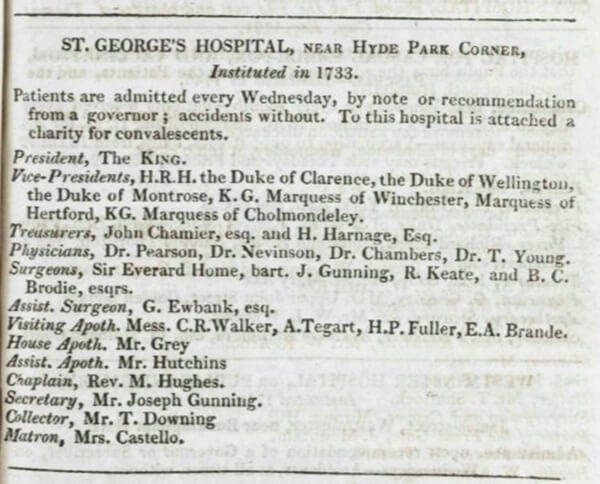

Issues of the Imperial Calendar show that a Mr ‘Grey’ had been first assistant Apothecary and then by 1824 House Apothecary at St George’s Hospital in London.[2]

He was still in Amersham as late as October 1859 when he acknowledged receipt of the LRCP certificate from Edinburgh.[3]

His wife Elizabeth was born in Monkwearmouth, County Durham: records show that he married Elizabeth Myers there by licence on 20 August 1825. The register entry gives his abode as ‘the parish of Amersham’, five years before Pigot’s Directory for 1830 shows listed him there with Thomas Brickwell and Edward Tallent.[4]

He appears in the electoral rolls for Amersham for 1837 and 1838 as an occupier of house and land in the High Street worth over £50 a year and the tithe apportionment maps dated 26 October 1837 show that he was living in a house on plot no 534 and renting Arbor Field (no 582) and an orchard (no 535), so he seems fairly prosperous. Research published on the Amersham history website indicates that he is likely to have lived at Apsley House while his fellow-surgeon, Thomas Brickwell, who had previously occupied no 28 had moved across the road to The Gables.

Directory entries from 1842 and the census of 1841 and 1851 confirm that he remained in the High Street.

One of his apprentices was Charles West (1816-1898) who would go on to become Britain’s first paediatric specialist and who founded Great Ormond Street Hospital. Charles was the second son of the Baptist minister Ebenezer West who ran a very successful boarding school with high academic standards in Amersham for many years before moving to Caversham in 1861 for larger premises and better rail links. The school continued there as Amersham Hall.

As a nonconformist West would have been unable to go on to study medicine at Oxford or Cambridge but he enrolled in 1833 at St Bartholomew’s Hospital where he was awarded prizes for medicine, forensic medicine and midwifery. He seems to have retained very good memories of his two years with Mr Gray and to have spoken about him often enough for his words to be quoted in his obituary:

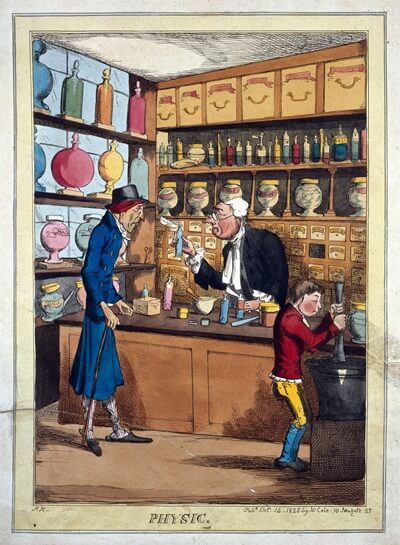

‘He has left it on record that the two things which he learnt while with Mr Gray were to compound medicines — a knowledge which he afterwards found of great service when prescribing for children —and a familiar acquaintance with Shakespeare, which doubtless fostered, if it did not create, the literary taste afterwards so conspicuous in his writings. In his later years he often said that the dying out of country surgeries and the enormous increase of the Pharmacopoeia were the cause of serious ignorance among practitioners as to the nature of their prescriptions.’[5]

The obituary also confirms that Mr Gray had been the Apothecary at St George’s Hospital in London.

A glimpse of the Grays’ domestic life is contained in the reminiscences of a nephew, Theophilus Woolmer. Invited to stay as a boy he remembered:

‘My reception at Amersham was of a formal character, but kind. Mrs Gray, in a very quiet way, expressed pleasure in seeing me. But she was exceedingly reserved and contented herself with saying that she hoped I would make myself comfortable. Mr Gray at first was grave and reticent; but when we sat round the tea table, he became very lively and humorous. My brother Thomas was his assistant. He was a dear, good-tempered fellow, and was a general favourite with patients, as well as with friends. But he was very closely confined to the dispensary — the practice being large and there being no other assistant at this time — and had not much opportunity of taking me about. I had daily rides, however, with my uncle, whose practice extended for several miles in every direction. And as he was very full of information and of anecdotes he made a most agreeable companion.[6]

Theophilus Woolmer (1815-1896) went on to become a Wesleyan Minister, as his father had been. Joseph Benson Woolmer was named as an executor in his uncle’s Will. They were both sons of Thomas Nathaniel Gray’s sister Jane who had married Samuel Woolmer in Maker in 1801. She died and was buried in Amersham on 29 April 1834, aged 52.

They were both buried in the churchyard at Amersham and the inscriptions read ‘Sacred to the memory of Jane Myers/ third daughter of the late Mr Myers of Monk Wearmouth Durham/ She died at Amersham December 13 1832 aged 29 years’ and ‘Sacred to the memory of/ Mrs Jane Woolmer/ relict of the late Rev Samuel Woolmer/ of Budleigh Salterton/ and daughter of the late Mr Thomas Gray of Kingsand/ both in the County of Devon/ she died at Amersham April 21 1824/ aged 52 years.’[7]

Mr Gray was also a nonconformist who held meetings for the town’s small group of Methodists in his home, Apsley House. As Steward he reported the attendance figures for the Wesleyan Methodists at a house in Bury End for the Religious Census of 1851. 23 attended the morning service and 28 came in the afternoon. After Mr Gray’s move to London the Methodists met in the Friends’ Meeting House before having their own chapel built in 1899.[8]

The Medical Officer could be drawn into conflicts taking place within the workhouse. In March 1853, after seven years’ service the nurse, Mrs Woodrow, asked the Guardians for an increase in salary. This was refused. 8 months later the Guardians had to adjudicate in a dispute between the Matron (Mrs Driscoll) and the nurse. Mr Gray spoke highly of the nurse’s conduct but also revealed that ill-feeling between the two women had long existed. The dispute centred on diets ordered for patients in the infirmary. The Guardians, to avoid future problems, ruled clearly that the Medical Officer was to decide on diets and could not be overruled by Master or Matron. The nurse was to have access to the diet book and was not to make enquiries about them in the kitchen. Mrs Driscoll perhaps saw this as her territory. According to the Minutes after ‘strong admonition’ the parties ‘agreed in future cheerfully to co-operate in their respective duties.’

As medical officer of the Union he was called to an inquest on a child who had suddenly deteriorated and died. Mr Gray had been attending the mother, Mrs John Saunders of Amersham Common, for a month and on his most recent visit had played with the child who seemed extremely healthy. When a severe cough developed a family member went to his house twice. Cough medicine was prescribed and the same medicine made up again by his assistant, Charles Searle Bailiff, who did not realise the gravity of the case. The jury felt that there was no negligence because neither Gray nor his assistant had been aware of the severity of the illness.[9]

When testifying as an expert witness during an inquest at Beaconsfield on a child who was thought to have died of croup he stated [in] ‘every case of croup, strong or weak [apparently referring to the constitution of the child], I should give tartar emetics to create sickness, and calomel to counteract the inflammation and to procure the removal of what that inflammation would deposit. But in a child of sufficiently strong constitution, I should bleed by leech or lancet in the beginning of the attack, but on no account afterwards.’[10] This is an interesting glimpse of contemporary treatments.

Once again he was called as an expert witness to an inquest at Chalfont St Peter in May 1858 where a child had died before being seen by the Medical Officer, the child sent with the printed order during a busy surgery having been incapable of giving any account of the urgency of the case.[11]

In December 1858 he and Thomas Brickwell both decided that it was time to hand on their duties as medical officer to a younger man. Mr Gray stated that he had been a Parish surgeon and Medical Officer for 27 years and strongly recommended as his successor ‘my nephew Mr Prowse, my partner since April last’. William Prowse had 9 months’ acquaintance with the duties and with the House and had previously been Medical Officer for the St Germans Union but had been in partnership with his uncle in Amersham since April 1858.

By 1861 Mr Gray had moved to 22 Cumberland Terrace, Bayswater, with his wife Elizabeth and it was at this address that he died on 25 October 1864. Another surgeon, his nephew Joseph Benson Woolmer proved the Will, and he left under £2,000. He was buried in All Souls Cemetery, Kensal Green, on 28 October, aged 71. Relying solely on such records it would be easy to assume that he had simply moved elsewhere on retirement. His nephew Theophilus Woolmer described what led Mr Gray, a highly respected doctor with a flourishing practice, to quit the neighbourhood. The account reveals much about Amersham society at the time, its religious divisions and the delicate understanding of etiquette which allowed people of different beliefs and social standing to coexist in at least superficial harmony.

‘He [Mr Gray] attended, for many years, all the principal families in the neighbourhood, until the unfortunate action of his wife deprived him of their patronage, and led to the introduction of another medical man into the town. He had married a lady of Sunderland, who was a very hearty Methodist and was exceedingly prim in her person and her manners.

Mr Gray had never hesitated to avow himself a Methodist; although Dr Rumsey — whose practice he had taken[12] — was a staunch Churchman. But as he never obtruded his religious opinions in company, and was not only a skilful doctor but a well-behaved gentleman also, his Methodism was no hindrance to his practice. He had established a small cause in the lower part of the town; and the Superintendent of the High Wycombe circuit had placed Amersham on his plan. But the service, at first, was only in non-church hours; and Mr Drake, the rector of the parish and one of his patients, though not liking the introduction of Methodism, made no objection; as Mr Gray always attended church on Sunday mornings and was one of the rector’s most thoughtful and attentive hearers. It used to be said that he – the rector – was not responsible for his sermons, which were obtained for him by some London bookseller, who was instructed to “let them be sound and brief, with a touch of the pathetic, and written in a good round hand, which could easily be read.” These instructions were, for the most part, well carried out; and the “touch of the pathetic,” when it came upon the rector in the pulpit unawares – for he did not always read his sermons before delivering them – sometimes made him pause and give ample vent to his feelings. He was a kind-hearted man, good to the sick and to the poor, and was much respected in the town and the neighbourhood. But he could not be called a spiritually-minded man, or a model clergyman. For he was a keen sportsman, and sometimes brought out his hounds on a Sunday, to be ready for a “meet” on the following day – a great contrast, in many respects, to Lord Wriothesley Russell, the rector of Chenies, whom Mr Gray frequently heard on a Sunday afternoon – when patients in that neighbourhood required his services.

The brother of the rector, who was lord of the manor, and owned, I believe, nearly the whole of Amersham, lived at Shardeloes, where the family he represented had resided for many generations. He was a lineal descendant of Sir Francis Drake and was a man of large means. Among other customs of long standing at Shardeloes, was one of inviting all the gentry in and about the town to an annual ball – which, by all accounts, was of a very first class character. No one was obliged to go; and no offence was taken with any who did not appear. Mr Gray received the invitation regularly up to the time of his marriage, but had always respectfully declined it. When he married, the invitation came as usual for himself and for Mrs Gray also; but was declined as before. Still it was repeated in following years, until Mrs Gray, whose righteous soul was indignant that such practices should go on without a word of reproof from any quarter, sat down to reply to one invitation, and lectured Mr. and Mrs. Drake so elaborately on the folly of dancing, and of parties being got together to indulge in that exercise, that they were hugely offended, and showed the letter, which contained Mrs. Gray’s denunciations, to the guests who had assembled at Shardeloes in response to their invitation. The result may be imagined. It was a kind of deathblow to Mr. Gray’s practice. And he, poor man! was entirely ignorant of what his wife intended to do, and heard nothing of it when done, until she told him after having struck the blow. He was deeply mortified and humbled – especially when he found that prompt measures were being taken to introduce another doctor into town, who should be a Churchman, and who had nothing to do with the Methodists. Yet although his practice greatly suffered by this most untoward circumstance, his principles were not shaken; and he continued to cherish and support the Methodism, on whose account he was now dishonoured and dismissed from many homes. Indeed, if possible, he was more diligent and devoted in promoting its interests than before. And by the introduction of a small organ – of which he took charge himself – and by increasing the accommodation of the preaching room, which rendered it more attractive and serviceable, he greatly benefited the cause. He also obtained better supplies for the pulpit than the circuit was able to provide – cheerfully paying out of his own pocket the expenses of students and others, who came from a distance to take the Sunday services.’[13]

[1] Part of the parish lay in Cornwall, part in Devon. See genuki.org for further details.

[2] The British Imperial Calendar for the Year of Our Lord 1824, London, p 339

[3] I am most grateful to Helen Watt for sending me a transcript of the above and to Estela Dukan, Assistant Librarian at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh for confirming that there are no records of TN Gray ever having been a student there.

[4] Many thanks to Helen Watt for showing me a copy of the register entry.

[5] British Medical Journal, 2 April 1898, p 921. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.1944.921.

See also The Lancet also 2 April 1898, pp 968-70 and https://www.hharp.org/library/gosh/doctors/charles-west.html

[6] Theophilus Woolmer, My Way and My Work; Some Reminiscences of My Earlier Life, 1892, pp 90-91. Thanks are due to Helen Watt for this extract.

[7] See for Monumental Inscriptions in St Mary’s Churchyard, Amersham,

https://amershammuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Monumental-Inscriptions-pdf.pdf

[8] Buckinghamshire Returns of the Census of Religious Worship, ed E Legg, Buckinghamshire Record Society Vol 27, 1991, no 13, pp 3-4 and Julian Hunt, A History of Amersham, 2001, pp 77-78

[9] Windsor and Eton Express, 29 March 1856, p 3

[10] Bucks Chronicle, 19 August 1857, p 2

[11] Bucks Herald, 15 May 1858, p 6

[12] This may be an error. Gray was in Amersham before his marriage in 1825. Rumsey died in 1824 but seems to have been succeeded in practice by his son, also named James Rumsey.

[13] Theophilus Woolmer, My Way and My Work, Vol 1, privately printed 1892, pp 90-93