By Alison Bailey

This article relates to the temporary exhibition in the museum, Sickness and Health, exploring how you might have been treated if you fell ill or were injured in the past.

Tudor Herb Garden

Plants were the first line of defence, and Tudor gardens, like the one at Amersham Museum, would have contained medicinal herbs. The more plants in the garden that could be used for several purposes, the better. Rosemary, a popular herb in cooking, also formed the basis of astringent medicines and lotions. Most householders would have been familiar with a plant’s medicinal properties. For example, the Apothecary’s Rose could be used for coughs and eye infections, Evening Primrose as a sedative and to treat whooping cough and the wonderfully named Sneezewort (wort indicates medicinal use), to relieve toothache.

The Plague

Amersham seems to have escaped the worst plague years of the 17th century. Parish records don’t show a huge increase in deaths, or recordings of “pest” for “pestilence” against names in the registers. In 1665, the year of the Great Plague in London, there were only 11 burials in total recorded here, with 19 the following year. In contrast, for the same years, High Wycombe recorded 96 plague deaths out of a total of 149, and 101 out of 144.

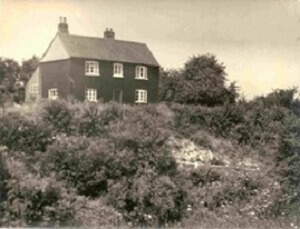

In 1622 a pest house, with its own plague pit, was established at Gore Hill House on the road to Beaconsfield. Parish Accounts show a payment of £2 16s 11d “for the relief of such as were suspected dangerous to the parish in time of infection.” Strangers were isolated there with any townspeople suspected of having the plague. Having a pest house outside the town probably saved many townsfolk. In the 18th century Gore Hill House was used to isolate cases of smallpox.

The Workhouse

Before Henry VIII’s Reformation, Amersham’s poor and sick would have been cared for by the Fraternity of St Katherine and other charitable organisations. Amersham’s first workhouse opened in 1617 in Church House in Market Square and later moved to different locations around the town.

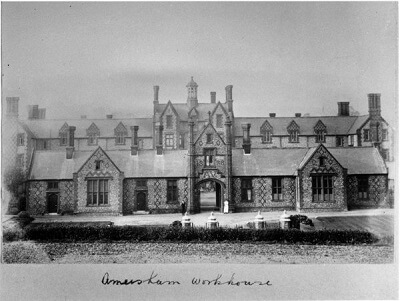

After the new Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, a decision was taken to build a new workhouse in Whielden Street. The Amersham Union Workhouse covered the parishes of Chesham, Great Missenden, the Chalfonts and Beaconsfield; 111 square miles, and around 18,000 people. The new building could house 330 inmates with separate wards for men, women, children, and vagrants.

A master and matron, usually a married couple, were in charge. The matron’s role was as housekeeper with a nurse also employed to care for the sick. The nurse, who would have had little training, was assisted by ‘pauper nurses’ who were women inmates. No formal nursing qualifications were available until the 1870s although the Medical Officer would have provided some training to ensure good care for his patients.

Each time the Amersham Board of Guardians advertised for the role, the main requirement was that the nurse was able to read and write (so that they could read the doctors instructions on the medicine bottles), be over 30 and “without encumbrances”. In addition to caring for the sick, the nurse also had to act as the midwife. The Medical Officer was only called in for the most complex births, when his fee was one guinea, plus the cost price of bandages and trusses!

Maria Woodrow

Maria Woodrow, a widow from Dorking, was employed as a nurse in 1846 at a salary of £20. Unusually an “encumbrance”, her daughter Maria, then aged 16, was allowed to live with her mother as she was helping in the school. In March 1853, after seven years’ service, Mrs Woodrow asked the Guardians for an increase in salary. This was refused. In November the Guardians had to adjudicate in a dispute between the Matron, (Mrs Driscoll) and the nurse. The Medical Officer spoke highly of the nurse’s conduct but also revealed that ill-feeling between the two women had long existed. The dispute centred on diets ordered for patients in the infirmary. The Guardians, to avoid future problems, ruled clearly that the Medical Officer was to decide on diets and could not be overruled. The nurse was to have access to the diet book and was not to make enquiries about them in the kitchen. Mrs Driscoll perhaps saw this as her territory. According to the Minutes after “strong admonition” the parties “agreed in future cheerfully to co-operate in their respective duties.” Only a few months later, Maria Woodrow resigned, having been appointed to the Lambeth Union Workhouse. As the salary stayed at £20 until 1886, when the job was advertised at £25, it is no wonder that the turnover was high, and the Guardians struggled to retain nurses!

The foundations of Amersham hospital

In 1868 the sick were separated from the able-bodied inmates and the infirmary wards improved. The coconut fibre workhouse mattresses were replaced by ones filled with feathers. Stone hot-water bottles were purchased, as were new bedside lockers. Proper sanitary facilities were installed, and each patient was provided with a comb and towel. An elaborate bell system enabled a patient to summon the nurse. By the end of the 19th century the infirmary nurse had usually been hospital trained and two of the matrons, Hettie Dean Waters and Alice Richards, were fully qualified nurses. Their role must have been more like that of a hospital matron than the workhouse matron of earlier times.

In 1903 a new infirmary was built on the site, followed soon after by a separate Isolation Block to replace the Pest House. By 1924 the infirmary was known as St Mary’s Hospital, and used by the local population, although the wealthy still went to High Wycombe, Aylesbury or London.

With thanks to Gwyneth Wilkie for additional research.

To find out more, do visit the exhibition, Sickness and Health at Amersham Museum and our website for details of our Up Close and Personal Session on Haddon’s Medicine Chest, 22 February, and other events.