VJ Day 75 Years Anniversary

On 15th August this year (2020) we will mark 75 years since VJ Day, the day when Japan surrendered, effectively signalling the end of WWII. Covid-19 will prevent some of the planned remembrance events from going ahead, just it did for VE Day earlier this year. At the museum we had hoped to run an event; since that’s not possible we have delved into local newspaper archives to find out how Amersham responded to the news 75 years ago.

There was mixed reactions on 15th August and the Bucks Examiner noted that Amersham’s response was a mixture of “jollity, thankfulness, lackadaisicalness and boredom.” This was in part due to the fact that many people had not heard the midnight bulletin declaring a two day public holiday on the 15th and 16th August, so many turned up for work only to find that few buses were running. Despite it being a wet day people rushed to put up decorations and formed long queues outside shops to buy fireworks and groceries for their celebrations.

On 2nd September 1945 Japan signed the surrender document and this date is also known as VJ Day. In Amersham a victory party was organised for the children living at Piggotts Orchard. Over 30 children enjoyed a special tea with an entertainer in the Nags Head and each child was also given a shilling.

A month later on 6th October a victory dance was organised in the Scout Hut at the top of Rectory Hill. 150 Polish men, who were given a home in disused army huts in Hodgemoor Woods were invited as well as women who had been helping at the Sycamore Canteen Club. A military band played and the hall was decorated with flowers.

A month later on 6th October a victory dance was organised in the Scout Hut at the top of Rectory Hill. 150 Polish men, who were given a home in disused army huts in Hodgemoor Woods were invited as well as women who had been helping at the Sycamore Canteen Club. A military band played and the hall was decorated with flowers.

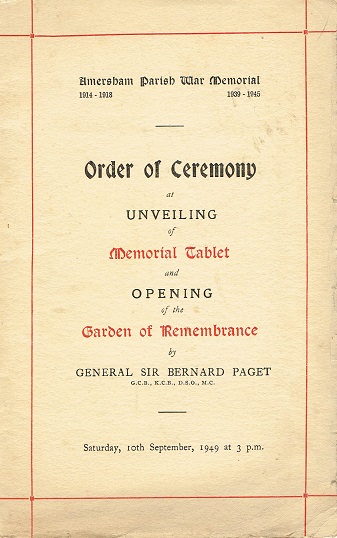

In September 1949 the Memorial Gardens in Amersham were opened. The WWI memorial was relocated from the churchyard into the newly created gardens, which now included a memorial to those who lost their lives in WWII.

You can find out more about the camp at Hodgemoor Woods here: https://amershammuseum.org/history/chesham-bois/beech-barn-camp/

You can find out more about some of the people who came to Amersham during and directly after the war here: https://amershammuseum.org/history/research/ve-day/

A Personal Story

Marian Borrows (one of our volunteers) has written up her father’s story as it relates to VJ Day, many families up and down the country will have witnessed similar experiences.

75 years Memories during a pandemic We celebrated VE Day, the end of the war in Europe, on the 8th May 2020, despite being in lockdown. It seemed important that we put aside our fears of the spread of the Covid virus and remembered those who sacrificed so much. Whielden Street managed to hold a (socially-distanced) party – bunting was strung along the street, family groups sat outside their front doors, eating cake and drinking tea (and stronger!). Vera Lynn’s voice floated down the street, couples danced and children played in the road.

75 years ago, I was three. Unlike my husband, who is 6 months younger, which is more important when you are 3 than when you are 78, I have no memories of celebrating back in 1945. This may have been because the war continued in the Far East. VJ Day, victory over Japan, was not celebrated until 15th August when Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender. This mattered to me because my father was still a prisoner of war of the Japanese.

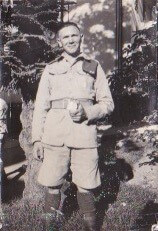

My father enlisted in 1941 and served as a crane driver in the Royal Engineers. I was born in November 1941 and he was granted compassionate leave to see me when I was a week old … and then not until late 1945. My Dad was a soldier in a picture, surrounded by jungle, eating an orange. It was only during lockdown that I have come to reflect that this early experience had a profound effect on my relations with my parents. Don’t get me wrong – I had a happy and loving childhood. My Dad was very good at making wooden toys and a whizz with car engines. So we often visited interesting places in Derbyshire and my love of history came from both my parents but emotionally we were never really close. I was an only child and my grandad (William Grose) was my rock and he certainly fostered my love of gardening. Fortunately, my parents’ relationship became closer despite their long separation.

My father enlisted in 1941 and served as a crane driver in the Royal Engineers. I was born in November 1941 and he was granted compassionate leave to see me when I was a week old … and then not until late 1945. My Dad was a soldier in a picture, surrounded by jungle, eating an orange. It was only during lockdown that I have come to reflect that this early experience had a profound effect on my relations with my parents. Don’t get me wrong – I had a happy and loving childhood. My Dad was very good at making wooden toys and a whizz with car engines. So we often visited interesting places in Derbyshire and my love of history came from both my parents but emotionally we were never really close. I was an only child and my grandad (William Grose) was my rock and he certainly fostered my love of gardening. Fortunately, my parents’ relationship became closer despite their long separation.

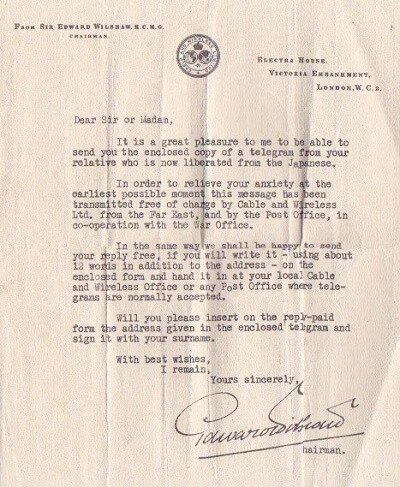

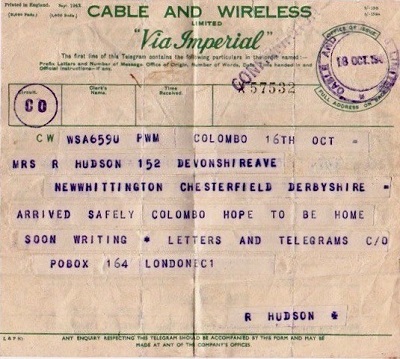

August 12th 1945 would have been my father’s 28th birthday. My mother had no idea of his whereabouts. Then a telegram (and accompanying letter) arrived on the 18th October.

My father arrived home in time to take me to see Father Christmas. I can remember being afraid, but whether it was of Father Christmas tears must have been very upsetting.

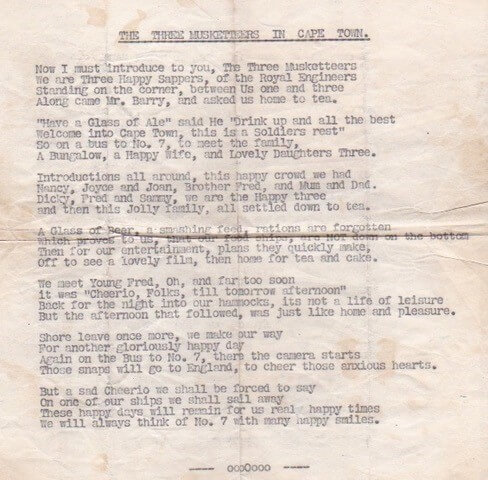

I have no letters or diaries of his war experiences and he talked little. Through his service record and one scrap of paper I have managed to construct a partial time line. In January 1942 he sailed on the Llangibby Castle, a Union Castle liner. The ship was torpedoed at 8.30 am on 16th January. His eardrum was burst and he became deaf in one ear. The damaged troop carrier limped to Free Town. Sierra Leone via the Azores. (The Daily Mail ran a story, because, by chance, it had a correspondent on board – I have the original newspaper and, bizarrely, the breakfast menu, these are now deposited in the Museum). He and his mates were befriended by a family in South Africa which they celebrated in a poem. This was then reported in a radio broadcast in Bombay where he arrived

on 10th April 1942.

From a few scribbled notes we followed his journey.

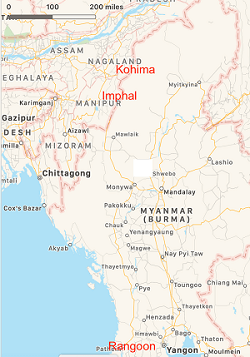

Chindwin to Dimapur

road impossible (Kalewa)

14th in out naga . Imphal 88 Plain

Kabaw D(?) (TAMU)

Kohima 50 days Battle

Bloodiest turning point

Crack nip troops

assam Chittagong Cox’s

Bazar nips retreat

(Manipur State)

Then we lose his whereabouts until the telegram. He did not talk of his experiences, just referring to the terrible things he had seen and the bloody fighting at Kohima. All his life he suffered from nightmares and bouts of malaria.

He was awarded 4 medals, (the 1939- 45 Star, the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939-45 and the Burma Star). The latter was awarded to those who served in the Burma Campaign from 1941 to 1945, but he only applied for them so that he could give them to his grandchildren.

Ironically, he only went abroad once more in his life and that was to deliver the crane he had worked on before the war when it was sold to Germany.

We have approached various sources to find out in which PoW camp he was held – the Army Record Office and the International Red Cross – and looked at the Japanese card index and the liberated prisoner of war interrogation questionnaires held in the National Archives at Kew. By a process of elimination we think it was probably Yangon (Rangoon) Jail. but there is still a mystery as to why his wife was not informed of his liberation until 4 months later. Hopefully, we may yet find the answer.

My parents died in 1996/7 within a year of each other. I think they thought, despite many hard times, their sacrifices in the war had been worth it. Their children and grandchildren did live in peace, had educational opportunities and benefitted from the NHS. If nothing else, lockdown gives me time to record this.

Marian Borrows

The Sumatra Death Railway and William Corlett

by Alison Bailey

Leading Aircraftsman William Charles Corlett from Amersham, who was also a Japanese Prisoner of War, did not come home. He was captured 8 March 1942 shortly after his RAF squadron (242) arrived in Palembang, Sumatra having fled Singapore just ahead of the Japanese invasion. The following year, after surviving as a PoW on meagre rations and hard labour he was forced to work on the Sumatra Railway, one of 4 so-called ‘Death Railways’.

Running 200 kilometres between the towns of Pekanbaru and Muaro, the Sumatra railway was built through thick jungle, swamps and marshes, through mountains and across rivers. The 5,000 PoWs and 100,000 romushas (Javanese slave labourers) working on the line used only manual tools while wearing little more than a loin-cloth. Bamboo huts along the line provided the only shelter and daily rations for the PoWs consisted of 200 grams of rice or tapioca per man. This was typically boiled with jungle vegetables, flavoured with sambal and, occasionally, a scrap of meat. Survivors told how additional protein was added to these rations by trapping rats and cooking maggots!

Cruelty, accidents, malnutrition and the chronically unsanitary conditions led to the deaths of 80% of the romusha workforce and 693 allied deaths. With no medicines or antibiotics most died from tropical sores, malaria or dysentery. William Corlett died 1st September 1944. He was 28 years old.

His family would have received a telegram telling them of his death some weeks or even months later. William had married Kathleen Macken in 1941 and lived with his in-laws at Formacs (c 30 -46), Green Lane, Amersham. His widowed mother, (Clara) May Corlett was the Sub-postmistress at 3 Anne’s Corner Chesham Bois (now 5 Bois Lane).

William Corlett was born in Portsmouth in 1916 but by 1933 he was living with his widowed mother at the Post Office in Anne’s Corner. His father, William Henry Corlett was a butcher in Portsmouth and had two daughters, Kathleen (11) and Doris, known as Dorrie (9) when he married May in 1911 after the death of his first wife the previous year. William Henry died in 1930 and May followed her step-daughter, Dorrie, to Amersham in 1933. Dorrie had married a soldier in the Royal Artillery, Horace Merwood, in Amersham in 1932. After living in married quarters in Woolwich for a number of years, in 1939 Dorrie was living with her step-mother and brother in Anne’s Corner. After May’s retirement in 1959 Dorrie (who had been widowed in 1950) took over as Subpostmistress until her own retirement in 1973. In 1963, May’s father, Charles Hutchings, died at the post office at the grand age of 100.

In the 1939 Register William Charles Corlett was listed as a grocer’s assistant. His future wife, Kathleen Macken, was listed in the Register as draper’s assistant. Her father was a builders’ merchant. In 1951 Kathleen married Franciszek Horaczek a German Jewish refugee. They stayed in Amersham. Kathleen died in 1993 and Franciszek in 2003 at the age of 104!

William is buried in the Jakarta War Cemetery and is commemorated on the Chesham Bois War Memorial.