This history of the Manor and Parish of Chesham Bois was written by Anne Paton and is reproduced here with permission

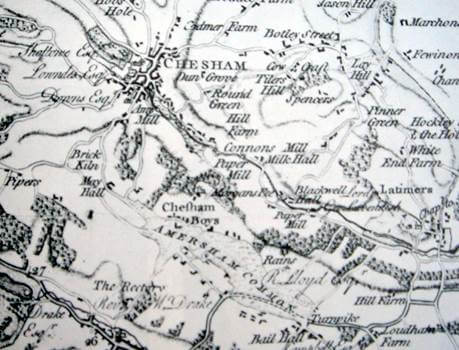

The Parish of Chesham Bois (pronounced ‘boys’) covers approximately 1 square mile and lies between the towns of Amersham and Chesham in the Chiltern District of South Buckinghamshire. (See here the current parish map.)

It is believed that the name derives from the Norman ‘de Bois’ family who were early Lords of the Manor. The original parish boundary which corresponds to the ecclesiastical boundary of the parish church of St Leonard’s extended down to the river Chess including Bois Moor (now Chesham Moor).

Chesham Bois has a history going back over a thousand years, but early archaeological evidence has so far been elusive. According to L Elgar Pike’s 1976 ‘A History of Chesham Bois’ “a prehistoric trade route came down over Ley Hill, across the River Chess and up the significantly named Hollow Way Lane and Bois Lane, to carry on across the then extensive commons to Amersham, up to Penn and on towards the South Coast. These ancient tracks were through largely uninhabited and often wild country. To guide those who used them, they were marked at frequent intervals by stone boulders of a distinctive type, called conglomerate or pudding stones. Many of them line the sides of the drive up from Bois Lane to The Warren and Chesham Bois House.”

The first definite evidence that a community of people was living here is in the Domesday Book, the great survey of his kingdom produced for William the Conqueror in 1086.

Domesday records a very small manor here of about 180 acres with 2 free men holding the land at the time of Edward the Confessor. Grouped with other manors in a wide area known as Cestreham (Chesham) it was then part of the Buckinghamshire estates of Leofwin, brother of King Harold who was killed with him at the battle of Hastings in 1066. These estates were given by the Conqueror to his half-brother, Odo, the warrior bishop of Bayeux. This little manor is not named in Domesday Book, but through Odo, it is possible to trace it in later documents to the manor, which was known as Chesham Bois by the early fourteenth century.

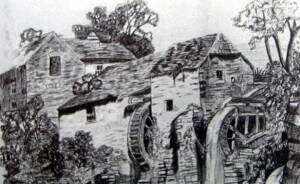

In 1086, seven men laboured here to get a living from difficult ground. Two-thirds of the land was farmed for the bishop’s benefit, probably visited at times by one of his men. Domesday lists their essential equipment, three ploughs, and their valuable asset of meadowland to feed their oxen. The ploughland may have been on the hilltop; the meadows would have been on the moor down by the Chess, where there were also two mills. The whole community may not have amounted to more than forty people: there is no evidence of where they lived.

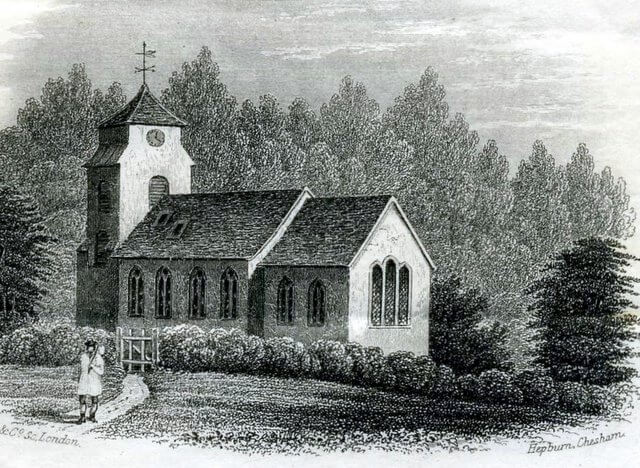

The history of Chesham Bois has been largely the history of the manor, its owners, and the farms and mills on the estate. The manor re-appears in the records in the early thirteenth century. In 1213, a legal document recorded the right of William de Bois and his successors to appoint a chaplain for his chapel, outside the bishop’s jurisdiction. That chapel is still in use today as the chancel of St Leonard’s Church and William’s house must have been nearby. Why the church is dedicated to St Leonard, (the patron saint of prisoners-of-war and women in labour), is unknown.

William of Risborough, the first known priest, arrived in 1216; by which time William de Bois may have granted the glebe land near the common for him to live on. A large ditch and bank surrounded it, sections of which can still be found. The present old and new rectories and The Parish Centre all stand within it.

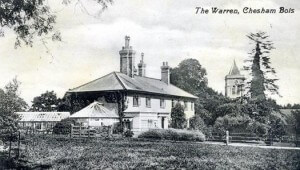

The de Bois family had gone by the beginning of the fourteenth century, leaving their name and their chapel. A succession of families held the manor after them including a grocer from London, a tax collector from Essex and Sir Bartholomew Brianzon who created a warren near today’s burial ground for rabbits and other small game to supply the manor house. A park for deer or cattle, remembered in the name ‘Long Park’, the road which runs through it, may have also been made in this period. According to the Time Team programme of 2006 the house closest to the church, which is called The Warren, may well have been on the site of the original manor house. The Time Team thought that the central part of the current house could date from the fifteenth century with further additions in Tudor, Georgian and Victorian periods.

More land was gradually brought under cultivation and the population slightly increased, possibly reflected in an extension to the Chapel where a small nave was added in the fourteenth century. By the fifteenth century, Chesham Bois had acquired the right to bury its dead and was being described as a parish. The people seem to have been living in small, scattered groups. It was thought that there might have been a village settlement near the church but Time Team did not find one.

The common, which was used to graze animals, and Bois Lane, may both date back to the little Saxon manor that was here before 1066. The origins of these things cannot usually be found in written record. As late as the nineteenth century, Bois Lane was described as ‘the main road from Chesham to London’. The lane the other side of the parish was used to connect Chesham and Amersham.

Until well into the twentieth century, when Amersham-on-the-Hill developed, Chesham Bois was much more strongly connected to Chesham and its fairs and market than to Amersham. In the medieval period there seems to have been rivalry between Amersham and Chesham which came to a head in the fifteenth century when the bishop agreed to end the long-standing Church tradition that the people of Chesham, Chesham Bois and Latimer should march in procession round the mother church of the area, St Mary’s in Amersham, at Whitsuntide. The event seems to have become a sort of local derby ending in brawling and serious rioting.

Disorder and lawlessness were familiar to Thomas Cheyne, who acquired Chesham Bois in the early fourteen thirties (at that time he had been living at Grove Farm across the Chess Valley). He spent a brief spell in the Tower of London in 1431 accused of heresy with a colourful reputation for violence, disorderly behaviour, torture and intimidation including threats to murder, an original ‘robber baron’. He had already been in the Tower in 1414, with his elder brother Sir John Cheyne of Drayton Beauchamp as supporters of a Lollard rebellion. For the next hundred years the Cheynes were known sympathisers with the Lollards, who denounced the pope and the church hierarchy and demanded that they should be able to read the Bible in English. The origins of the Low Church tradition of St Leonard’s may go back beyond the Reformation to the fifteenth century Cheynes.

For a brief period Chesham Bois and Chenies Manor were linked. In 1445 Thomas bought Chenies – confusingly from another family called Cheyney who had been there for more than two hundred years. He sold it to his brother, Sir John, who began to build a new brick house there, part of which survives. What Thomas did at Chesham Bois is less certain. CVAHS and Time Team excavated an important hearth on the manor house site, which may be connected with him. When Sir John died, Chenies passed through his widow to the Russells, later Earls and Duke of Bedford. Their ambition and court connections brought the royal visits from Henry VIII and Elizabeth in the sixteenth century.

The Cheynes of Chesham Bois didn’t have the same royal connections. Nevertheless in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they emerged as an important county family, several times serving as Court Sheriff, the chief royal representative in Buckinghamshire, bringing the business of the courts to Chesham Bois. Time Team found brick fragments of their manor house in Chesham Bois House and its gardens and evidence of considerable rebuilding. They developed a well-organised agricultural estate, with brick and timber buildings for four tenanted farms – Mayhall Farm and Bois Farm were on the road between Amersham and Chesham, Ivy House Farm in the Chess Valley, and Manor Farm near the common which supplied the Manor House. Large flocks of Cheyne sheep were run on the hilltop at Grove Farm, where Cheyne sheep bells have been found. (Click here and here for more information.)

There were several substantial mills on the river Chess, part of a chain of mills from the Bury to Sarratt Mill, near Rickmansworth. The other mills were Amy Mill (later known as Rose Mill), Lord’s Mill (later Bois Saw Mill and Canada Works), Cannon’s Mill (also known as Middle Mill), Weirhouse Mill, Blackwell Hall Mill and Bois Mill (also known as Chesham Bois Mill). At different times these worked as corn mills, fulling mills (for processing cloth), paper mills and even a saw mill (Canada Works) and were important employers in the parish although only Amy Mill and Bois Mill were actually within the parish boundary. The men who worked there and on the farms seem to have lived in scattered groups around the parish, as again no evidence of a village has appeared until the current village grew with the arrival of the railway in the late nineteenth century. Brick making, watercress growing, woodturning, straw-plaiting and lace making were also local industries.

The centre of the life of Chesham Bois was the Manor House and the Church, particularly busy in the early seventeenth century. In 1620 Francis Cheyne found a bride from the Fleetwoods of Missenden Abbey, the local ‘new money’. By 1630 they had three small boys and in the spring of that year Anne Cheyne kept a little notebook of ‘a list of victuals consumed over several weeks.’ There were large quantities of meat and poultry, custards and milk puddings, and apple pies using up last season’s fruit. Pigs’ trotters were popular, fish and vegetables scarcely mentioned. Bread was baked for the whole household and for the poor – 67 loaves in one day – perhaps in the large brick range excavated by Time Team dated to that time. The day after Anne’s last entry, she gave birth to a fourth son: within a week she was dead. The parish registers record that she was buried the day her son was baptized. Someone kept her little notebook, recording after her last entry that it was ‘in her own hand’. It now lies thousands of miles away in the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, with a collection of miscellaneous Cheyne papers in the Ellesmere Papers purchased for the library in 1917.

What happened in the following years and the early years of the Civil War remains to be discovered. Francis Cheyne’s son Charles, who was just eighteen, succeeded him in 1644. Obviously a supporter of the King, he appears as Captain Cheyne in the Royalist Army, achieving notice by winning the heart of a famous Royalist heroine and heiress, Jane Cavendish, daughter of the Marquis of Newcastle. Her father thought Cheyne not good enough, but she would have no one else. Chesham Bois may have been under the influence of Parliament for a time as Charles Cheyne, like many Royalist, spent several years abroad. ‘Mr. Whitby’ recorded in the list of rectors may have been a Puritan minister at St Leonard’s.

Chesham Bois may not have seen much of the couple as, with Jane’s fortune, Charles purchased the manor of Chelsea (where their name lives on in Cheyne Walk), which was convenient for Charles II’s court after the Restoration, and in 1681 he was created Viscount Newhaven. Great gardens were made at Chelsea, and it is possible that the considerable formal gardens laid out round the Manor House at Chesham Bois (then usually referred to as the ‘Mansion House’) were made for him. Gardens are hard to date, and some of these, including a bowling green, may have been created for his father, Francis, or even earlier.

William, Charles Cheyne’s only son, was an ambitious and forceful man, and deeply involved in County politics, engaging in the early campaigns by the Tories to keep the Whigs out of Parliament. He arrived at the mansion house in Chesham Bois with Sir Roger Hill of Denham and a band of supporters and held a three-day party for voters soon after he inherited from his father in 1698. Those who refused to promise their votes (then made in public) were thrown out of the house. The next year Lord Cheyne challenged the Lord-lieutenant of the County over the right to lead the Quarter Sessions procession through Chesham. They fought a duel on Town Field; Cheyne lost and was ‘given his life’. He continued electioneering for many years. In 1715 he wrote urging Lord Verney of Claydon to come in support and stay with him ‘Boys and myself shall be at your service with a warm bedd and a hearty welcome’.

Whether Lord Cheyne was interested in the agricultural improvements then being introduced is uncertain. It was in his time that the Park was divided up and Long Park field created. Buckinghamshire Record Office holds a map made for William Lord Cheyne in 1716 showing ‘The Park’. The survey and map ordered by the Duke of Bedford when he bought Chesham Bois in 1735 shows ‘The Old Park’ with the new fields. That map deposited in the Russell papers in the Bedfordshire and Luton County Record Archives in Bedford, gives a most detailed picture of the land use in the parish, with information on the tenancies in the Field Book that accompanies it. It also shows the footprint of the mansion house, used by Time Team when parts of the walls were excavated. There is no picture of the house.

Lord Cheyne was the last of his line. When he died in 1728, Chesham Bois passed through his wife’s family to the Duke of Bedford, who had no interest in the mansion house. Described in the Field Book as ‘only fit to be pulled down’ it was nevertheless let to two respectable tenants; but it was finally demolished and the materials sold. A corner of it survives with a massive chimney, inside the structure of Chesham Bois House. The Duke of Bedford at the end of the eighteenth century sold off the land in Chesham Bois in several separate lots, keeping the lordship of the manor, later sold to Mr. John William Garrett-Pegge in 1903, who then re-named his house Chesham Bois Manor and assumed the role of Lord of the Manor.

During the period without a resident lord of the manor, the Rector emerged as the leader of the community. In the eighteenth century, Thomas Clarke ran a school from The Parsonage, as it was then called, for local boys and young gentleman intending to enter the Church. The memorial they erected to him is in the Church. He tended the parish with care, as did his successors in the nineteenth century. The population began slowly to increase, from 135 in the 1801 census to 351 in 1881. In the early 1880s, just before the railway arrived, the church building was renovated and extended and the

tower was added. The chancel arch, which was the doorway of the De Bois chapel, was removed and used as the gateway to the Churchyard until it crumbled. Only the bottom stones remain.

There were other changes in the nineteenth century. The Duke of Bedford erected a new rectory in the Russell style in 1833, and gave permission for a school on the edge of the common, replaced in 1894 by a new building nearer the Church. The ‘New Road’ was built around 1827, diverting part of the old lane between Amersham and Chesham. This drew traffic away from Bois Lane and later attracted building development when the Bois Farm estate was sold early in the twentieth century.

The site of the old mansion house was cleared, some of the materials sold to the local brewer, Mr. Weller, for his new house ‘The Plantation’. A gentleman’s villa, Chesham Bois House, which includes an exquisite staircase, was built around a remaining fragment. The Tithe map of 1838 shows the house with a small garden and next door the house, which is now called The Warren, had become a dairy farm. The avenue to the old house and the meadow survive. All are now in a conservation area.

The last Lord of the Manor, William George Garrett-Pegge died in 1979, the year that the Parish Council finally bought Chesham Bois Common from him, having rented it for a peppercorn rent since 1953. The Common consists of some 40 acres of amenity woodlands, including bridle, footpaths, and dells as well as two large open areas. One of the open areas contains the pond and the other the cricket pitch, which has been used by the village cricket club for over 100 years. In 1992, Chiltern District Council included a large part of the Common in the formally designated Chesham Bois Conservation area, defined as “an area of special architectural or historical interest, the character of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”.

Common towards South Road around 1905

The arrival of the Metropolitan Railway at Chesham in 1889 and Amersham in 1892 encouraged a steady growth in population in the twentieth century, with many people commuting to work elsewhere. “Metroland” arrived next door to Chesham Bois and the thriving, busy community soon had a vigorous new neighbour in Amersham-on-the-Hill.

After the sale of the Manor Farm Estate in 1896, Chesham Bois gained a new focal point. A cluster of houses and small shops developed, rapidly becoming known as ‘the village’. It was there, on the common near Anne’s Corner, that the Parish Council created by the Local Government Amendment Act in 1894, decided to put the War Memorial after the First World War.

In 1934 more re-organisation of local government changed Chesham Bois. The Victorian terraces and little shops which had grown up on the Moor from the nineteenth century, the council houses and watercress beds were assigned to Chesham, where many of the people who lived on the Moor worked. The ancient ecclesiastical parish was unaffected and Bois Moor remained part of the parish of St Leonard’s, Chesham Bois. The community of the Moor kept a strong identity of its own. This boundary change meant that Chesham Bois lost its only public house. The Unicorn Pub in Bois Moor Lane, which was first recorded in 1770, had been rebuilt in 1889 and was to have been renamed the Railway Hotel (the Chesham branch line originally stopped here on the Moor). It was unusual in that the front rooms were in Chesham Bois and the back rooms in Chesham! See “Pubs and Inns of Chesham and Villages” by Ray East, Keith Fletcher and Peter Hawkes.

A re-organisation of postal districts came after the Second World War. The Post Office stipulated that Amersham was their required postal address for houses in Chesham Bois: Chesham Bois was redundant, a decree vigorously contested by many of its inhabitants who claimed correctly that it was not, and never had been, part of Amersham.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, with a population of over 3000, Chesham Bois keeps its distinct identity, most formally expressed in the annual Remembrance Day Service at the War Memorial. An active Parish Council, thriving biennial fete on the Common, vigorous organisations, schools and churches with the most recent development of Carols in the Village at Christmas are all signs of a living community.

In recent times excavation of the manor house site by CVAHS and Time Team’s visit has helped to remind people that Chesham Bois has existed for many centuries but the story is not complete; further documentary research, archaeological investigation and local enquiry will produce more information and may change interpretation of what is now known.

Further Information:

Chesham Bois: A Celebration of the Village and its History

Produced by Chesham Bois Parish Map Group, this contains much interesting information, some of it based on the recollections of long-term residents. It contains a brief list of sources. Copies are available in the Chesham Bois Parish Office.

Chesham Bois Manor, Home of the Cheyne Family for 350 years: Historical and Archaeological Investigation

The work of the Chess Valley Archaeological and Historical Society (CVAHS) and Time Team is fully written up and illustrated with historical background and full references. Published in Records of Buckinghamshire Vol 50 2010.

Time Team: Channel 4’s team who followed up CVAHS work with further excavations in 2006, causing considerable local excitement. The programme they made was shown with the title “The Cheyne Gang”.

1925 A History of The County of Buckingham: Volume 3

“Pubs and Inns of Chesham and Villages” by Ray East, Keith Fletcher and Peter Hawkes.