The Suburbs before Metroland

Today, we take the suburbs around our cities for granted but, as recently as the early 1900’s, you didn’t need to venture far out of London to find open fields. Areas like Wembley and Harrow were undeveloped. Familiar names on the Tube Map today, were small isolated towns or villages.

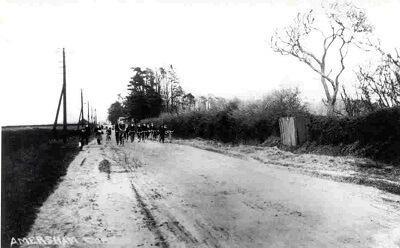

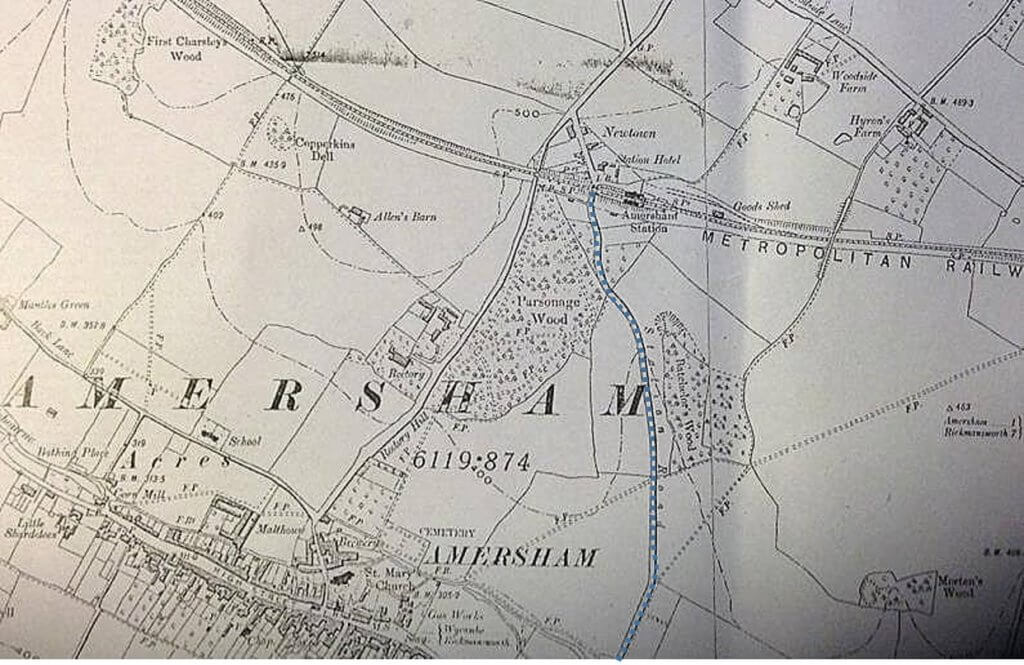

What we now know as Old Amersham is long established having been mentioned as Agmodesham in the Domesday Book. But, prior to the railways arrival, there were only a scattering of buildings in what is now Amersham-on-the-Hill, Chesham Bois and Amersham Common, with even less at Little Chalfont. Their development came about due to an early twentieth century phenomenon, Metro-land or as we now know it Metroland.

The Start of Commuting

London’s population was around a million at the time of the 1801 Census, by 1850 it had doubled and by 1900 it was around six million. Overcrowding and insanitary living conditions were rife, particularly in the east of the capital, as clearly demonstrated by the excellent work of social reform campaigner Charles Booth.

To accommodate London’s population growth, the city needed to grow outwards. However this was easier said than done, road conditions were poor, often impassable in bad weather. Horse drawn buses were the only public transport option. Up until the mid-eighteenth century, the norm for both the working and middle classes was walking to work, limiting where they could live.

Although the coming of the Railways made commuting possible, it wasn’t a priority for the railway companies. The revenue from long distance goods and passenger traffic was more important than picking up passengers from stations in sparsely populated areas.

Despite this lack of interest, commuting grew especially for the better-off, anxious to leave London’s congestion and pollution behind. Grand houses were built conveniently for the station in areas now considered suburbs.

Commuting by other classes increased following William Gladstone’s 1844 Railway Act. This mandated that every line must provide:

- At least one train each way, each day with seated and covered provision for 3rd class passengers

- The fare was capped at one old penny per mile (not cheap then)

- The minimum average speed was 12 miles per hour

Known as Parliamentary Trains, they were often timed inconveniently. Despite this more and more Londoners opted to commute, such was the desire for a better life away from the city. Gradually some railways such as The Great Eastern based at London’s Liverpool Street saw the potential of commuting.

The Metropolitan Railway

London has no Grand Central Station like New York’s. Instead, each line radiates out from the capital from its own station. Each station was built on what was then the periphery of the city, having been barred from entering it by the authorities. For a city already struggling to cope with the increasing population, this made congestion in the central area even worse as people and goods used the streets to get from station to station and station to city centre.

Something had to be done!

The Metropolitan Line can be credited to Charles Pearson, a solicitor at the Corporation of London. He proposed building an underground line from Paddington in the West to the City of London, with links to other main line railways along the way. The Great Western Railway, being the most remote, was a key supporter of plan.

Raising capital and overcoming obstacles both political and physical was not easy (nobody had ever done this before!). From Pearson’s initial proposal in 1846, it took until 1863 before the Metropolitan Railway linked Paddington to Farringdon Road in the City of London. This was the world’s first underground railway. Unlike the later “tube” lines tunnelled deep underground, the Mets construction involved digging up the road, and then bridging the railways path with a brick arch before relaying the road, so called “Cut and Cover,” an expensive and disruptive process. Regular vents, still evident today allowed steam from the locomotives to escape.

Carrying both goods and passengers, it was an instant success despite the unpleasant polluted travelling conditions. Although now only a passenger only line, freight traffic was equally important. Below London’s Smithfield meat market there was a network of rail sidings, now used for parking. It connected with the Great Western at Paddington, the Great Northern Line at Kings Cross, the Midland Railway at St Pancras and with the Great Eastern at Liverpool Street. Normal size trains could pass under London from West to East, something which will only be possible again when Crossrail finally opens. Such was the success, additional tracks known as the Widened Lines, now used by Thameslink services were constructed at the Eastern end of the line.

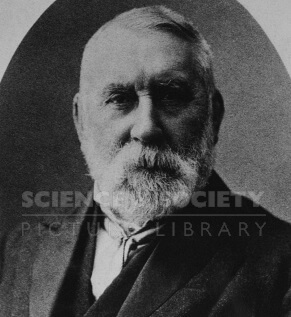

Sir Edward Watkin

Manchester born Edward Watkin was a giant figure in the development of Victorian railways, at the peak of his power he was a director or chair of railways in the UK, North America and France. Having become chairman of The Metropolitan in 1872 he was the driving force behind expansion and in linking routes with other companies.

Expansion

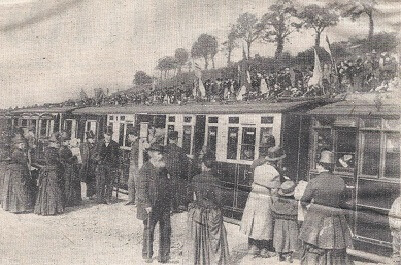

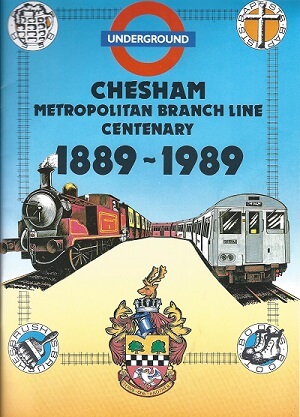

Under his chairmanship, the company had ambition beyond its pioneering line, so it set about extending modestly eastward (Moorgate) and westward (Hammersmith) and more ambitiously to the north-west. Harrow was reached in 1880, Chesham in 1889 and Amersham in 1892 when the extension to Aylesbury opened. It eventually reached Verney Junction about 50 miles from London. Later branches were built to Uxbridge, Stanmore (now on the Jubilee line) and Watford.

Chesham is served by a single track branch line terminating in the town at the well preserved Metropolitan Railway Station still complete with an old signal box and water tower. A planned but never built extension would have joined the Met to the LNWR (today’s West Coast route out of London Euston) between Berkhamsted and Tring, providing a through route to the North. Chesham was a small industrial town; the site of its once extensive goods yards are now used for the station and Waitrose supermarket car parks.

National and International

The Great Central Railway was completed in 1899, connecting the existing Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway to London Marylebone. Again his vision is evident, it was built for high speeds and to suit the larger European loading gauge (BERNE) allowing for larger freight and double deck trains. The Metropolitan tracks were used between Quainton Road and Harrow-on-the-Hill; until the line was closed by Dr Beeching, Great Central expresses could be seen at Amersham. The northern destinations for the proposed HS2 line bear close similarity to his line, prompting the question, whether it should have ever closed.

Sir Edward Watkin was a visionary and without doubt his most ambitious scheme was his Channel Tunnel. The plan was to link Manchester to Paris using tracks all under his influence or control, The Great Central, The Metropolitan, The South Eastern Railway and France’s Chemin de Fer du Nord. Construction of his Channel Tunnel began in 1880, it reached over a mile under the Channel before politics and military concern stopped further digging.

To relieve congestion additional “fast” tracks were laid South of Harrow on the Hill to the Great Central Railway’s Marylebone Station. From Amersham and some other stations, travellers still have the choice of taking the Met to the city, or the Chiltern Line to Marylebone. On the Met itself, additional tracks allow for some peak hour trains to run “fast” not stopping at all stations, unique on the London Underground.

The Challenge of Growing Traffic – The Answer, Metroland or Metro-Land

Under Watkin the Metropolitan had expanded considerably. Whilst other railway companies gladly used it tracks, its own services in the expansion areas under performed. Most of the towns and villages served were small with agricultural economies. Chesham with less than 10,000 residents was the most significant industrial town. The earlier main lines had taken the prime routes and reached further to the Midland and Northern industrial cities.

In 1904 Sir Charles McLaren Bart took over as Chairman, an important time. The railway was being modernised to use electricity for its passenger services through its underground tunnels. This was a costly undertaking so revenue improvement was crucial. Robert Selbie joined as general manager in 1908, it was under this management team that the fortunes of the company were turned around.

Their plan to boost revenue was simple (and revolutionary) if the traffic wasn’t there, they would create it!

The Creation of Metroland

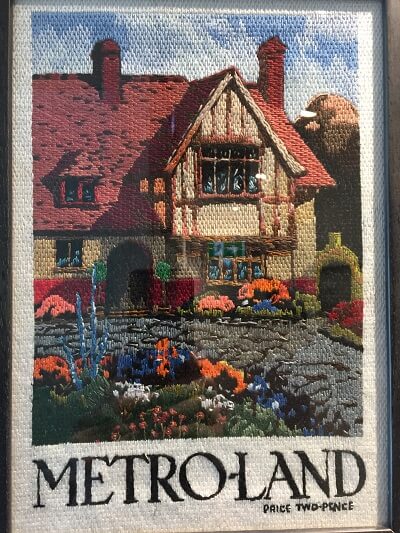

Marketing as we know it now was in its infancy one hundred years ago. The Metropolitan Railway was an early adopter, its goal to generate traffic. In 1915 its marketing department is credited with renaming a booklet “The Guide to the Extension Line” to The Metro-Land Guide,” then with a hyphen. The annual Metroland guides promoted the countryside the line served as a place to visit for recreation but most importantly as a place to live.

Unlike other railway companies, the Metropolitan had an advantage, whereas others had to sell surplus land, they were allowed to retain theirs. So, through a nominally independent company, “Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Limited,” acres of land along their tracks were available to sell and then to house future customers.

Marketing went into full gear with annual Metro-land magazines, promoting an idyllic country lifestyle with beautiful homes within easy reach of London. From the end of World War One through to the 1920s, Metroland boomed, as London’s new middle class taking advantage of affordable mortgages fell for the companies advertising. The “Live in Metro-land” slogan was even engraved on the carriage door plates!

Metro-Land architecture was typically conservative rather than revolutionary with a strong leaning to so called Tudorbethan styling for housing and shops. Towns such as Harrow, Pinner and Wembley are all Metroland developments though now greatly expanded.

An exception is “High and Over”a Grade II* modernist building in Amersham, it was started in 1929 and completed in 1931 by Amyas D Connell (1901-1980) for Bernard Ashmole (1898-1988).

The Success of Metroland

Such was the popularity of commuting that the new towns along the Metropolitan expanded rapidly during the inter war property boom. Other lines out of London were quick to copy the Metropolitan’s lead, creating new suburbs and their own commuter traffic. But Metro-land stood out, and it was unashamedly aimed at the middle class (and above) Commuter and, for a while, luxury Pullman carriages were provided. This encouraged many successful London businessmen to build homes , sometimes weekend homes at the Metro-land extremities within the Chiltern countryside.

Such was the popularity of commuting that the new towns along the Metropolitan expanded rapidly during the inter war property boom. Other lines out of London were quick to copy the Metropolitan’s lead, creating new suburbs and their own commuter traffic. But Metro-land stood out, and it was unashamedly aimed at the middle class (and above) Commuter and, for a while, luxury Pullman carriages were provided. This encouraged many successful London businessmen to build homes , sometimes weekend homes at the Metro-land extremities within the Chiltern countryside.

As a result London moved outwards rather than upwards. The population density of central London is still a fraction of that of Paris, although both regions have similar overall populations.

Londoners are more likely to commute further and live in a house with a garden than their French counterparts.

London Underground A60 Stock

Until 1961, the Metropolitan Line operated as far as Aylesbury. Trains were steam hauled between Rickmansworth and Aylesbury involving a rapid changeover of locomotives at Rickmansworth. As a decision was made to only electrify as far as Amersham, from 1961, services to Aylesbury were operated exclusively by British Railways diesel services, as is still the case for today’s Chiltern Railways.

Until 1961, the Metropolitan Line operated as far as Aylesbury. Trains were steam hauled between Rickmansworth and Aylesbury involving a rapid changeover of locomotives at Rickmansworth. As a decision was made to only electrify as far as Amersham, from 1961, services to Aylesbury were operated exclusively by British Railways diesel services, as is still the case for today’s Chiltern Railways.

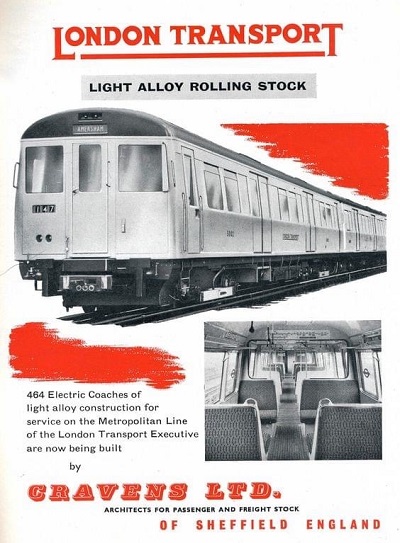

For their newly upgraded Metropolitan Line, London Transport ordered new rolling stock from Cravens of Sheffield. Unlike the stock on other London Underground lines, the new A Stock trains, (A stands for Amersham) were much more spacious and included luggage racks (now sold in the London Transport Museum) and umbrella storage. Rated at 70 MPH, they were also the fastest.

From their introduction in 1961, the A Stock trains remained in daily service for over fifty years, being finally withdrawn in 2012. Sadly, today’s S8 stock, lacks the comfort and number of seats of their predecessor.

From their introduction in 1961, the A Stock trains remained in daily service for over fifty years, being finally withdrawn in 2012. Sadly, today’s S8 stock, lacks the comfort and number of seats of their predecessor.

Amersham – Living the Metroland Dream

Within the M25, London’s massive growth means that the open fields, the Metro-Land magazine promoted are now less easy to find. Infill and redevelopment have played their part to erase the Metroland image.

Outside the M25, the Metroland ideal is still alive at Amersham-on-the-Hill, the last of the original Metroland towns. The town enjoyed protection from over development by former land owners, and more recently from the green belt and by being part of “The Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.”

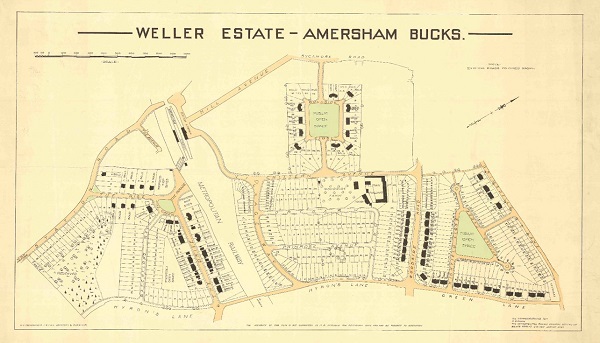

Amersham’s Weller Estate was the last and furthest from London of the Metro-land estates. The Weller Estate was launched in 1930. It consisted of 78 acres of land north and south of the station between Grimsdell’s Lane and Stanley Hill Avenue, bought from the estate of George Weller for £18,000. The plans included 535 houses and 51 shops, not all were built.

Four types of houses were proposed, ranging in price from £875 to £1,200. They can be found today around the station; Woodside Close, The Drive and The Rise.

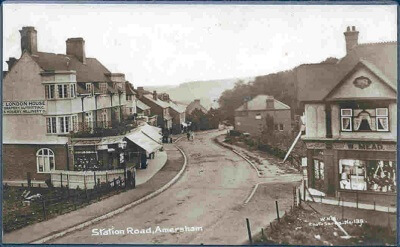

Amersham-on-the-Hill was a creation of the railway, there was little there before it arrived. It’s Metroland background is still clear to see many of the houses and shops still retain elements of the “Tudorbethan” architectural style.

Chesham Bois, just north of Amersham on the Hill features many buildings in the Arts and Craft style, many designed by J. H. Kennard.

Old Amersham by comparison is recorded in the Domesday Book. Its historic main street owes its survival to the local landowner refusing the railway permission to cross his land forcing it further up the hill. The Old Town is where Amersham Museum is situated, housed in the towns oldest surviving medieval house. Old Amersham is a delightful place to visit with many historic buildings, hotels, restaurants and its award winning Memorial Gardens.

Ralph Hilsdon