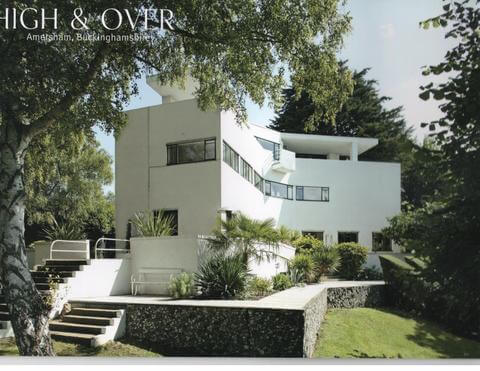

This Grade II* modernist building was started in 1929 and completed in 1931 by Amyas D Connell (1901-1980) for Bernard Ashmole (1898-1988) Professor of Classical Archaeology at London University and head of classical sculpture at the British Museum, who was an adviser in ancient sculpture to Getty and helped in the creation of that collection. The building caused considerable local concern when it was built. It has a concrete frame, externally of brick and with concrete blocks internally. It is Y-shaped, designed to catch the sun and views across the Misbourne valley, with a hexagonal centrepiece incorporating the main and garden entrances and a projecting staircase. It was known locally as the “aeroplane house”, either because of the propellor Y shape or because the two canopies looked like a bi-plane. (See an aerial photo.) High and Over was the first Modernist “International Style’ country house. Connell and Ashmole had met at the British School in Rome .

Ashmole was looking for a hill top site overlooking a bowl and valley to create a Modernist Roman Villa. The site in Amersham was purchased from the Tyrwhitt-Drake Estate for its topography and the amphitheatre was a chalk working that was further landscaped to create ‘the velvet hollow’.

The north wing of house originally housed the kitchen and servants’ quarters. The upper floor has two concrete canopies over a rooftop garden, incorporating hooks for hammocks and swing, and a sandpit. The central hexagonal hallway retains the original polished limestone floor inset with glass and the central fountain has now been restored. The central circular opening to first floor has a solid balustrade, the first floor being reached via a spiral staircase with a similar balustrade.

The building is described by English Heritage as “of outstanding importance as the first truly convincing essay in the international style in England……….. It is the first work by Connell, who with Basil Ward and Colin Lucas formed the most important architectural practice designing modern movement houses in the inter-war period.” It was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art NY in 1937 in an exhibition titled Modern ‘Architecture in England’. Connell was influenced by Le Corbusier. For many years the ownership of the house was split in two, but both parts have recently been bought by one owner, the house is being restored and the original floor plans have been reinstated.

The 16 acre estate (now called Highover Park) included the Lodge for the housekeeper and gardener and bachelor guests would stay there, cared for by the housekeeper. Connell and Ashmole also designed the Sun Houses on the approach road to the estate, probably to offset the high cost of building High & Over. The water tower and fives court have been demolished but a sad loss is one of the world’s largest and most elaborate Modernist gardens based on Guevrekian’s Garden of Water and Light at the Villa Noailles, but never fully completed. This comprised terraces, walks, a gallop, fish ponds, water gardens, fruit orchards, flower gardens and a tennis court all in Modernist style. It was largely built by Ashmole and George Marlow, the gardener who lived in the cottage with his wife May. The house although designed as a Modernist building also had a relationship to ancient Roman villas and the garden designs of Pliny as well as Renaissance villas. The house and gardens formed an elaborate geometric and metaphysical star shaped scheme that radiated out from the hexagonal hallway with a circular fountain at the centre. The Modernist garden has been obliterated by a 60s housing development but part of the Roman garden with its swimming pool survives as the setting for the Grade II* listed building. When built, steps lined with cypress trees went down opposite the main entrance to the house down to the pool, showing the Italian influence. The garden was originally planted with Corsican pines, Monterey Cedars and Black Poplar. The interior of the house was to have been designed by Syrie Maugham in her characteristic white on white style, however Dorothy Ashmole put her foot down and introduced an extraordinary scheme of metallic silver and bronze interiors.

There is a British Pathé news clip showing the house in 1931 shortly after it was built. See also an article on the Amersham.org.uk site and more detail and plans in an extensive and informative 2010 article.

The family moved out of High & Over in the 1950s and it was then bought by D L Mays, the Punch cartoonist. In 1962 or 1963 it was bought by Frank Briggs, an architect, who split the house to accommodate two families. It was not then a listed building. Because the original plans had been lost in the blitz in London, Michael Thomas (then an architectural student) made new measured plans in 1962 which he has kindly presented to Amersham Museum and to the current owners together with some photographs. A selection is shown in the “gallery” below. There is also a photo of a model showing the possible development of surrounding houses, designed by Werner Rosenthal (an Amersham architect), which was given outline planning permission in 1962. The development changed hands and what was actually built was very different with rather more houses.

Although High & Over was first listed Grade II in 1971, it is only more recently that it was listed Grade II*, recognising its high status. The house had been divided into two dwellings in the 1960s, but was returned to a single unit a few years ago when the then owners of one part of the house, the Halleys, acquired the other part. The current owners, an artist and an art historian/interior designer, are continuing to carefully restore the house.

The “Sun Houses”

There are four reinforced concrete houses built against the hillside by the same architect as High & Over and listed grade II.

Click on any of the photographs below to enlarge it and to see the description. Then click on forward or back arrows at the foot of each photograph. To close the pictures, just click on one.

High & Over and Bernard Ashmole

This article was written by George Worrall for the Amersham Society/Museum newsletter in 2007 and is reproduced with permission.

All those who are interested in local history are likely to be aware of the ‘aeroplane’ house. The controversial design of High and Over with its three elongated elements set at 120 degree intervals apart must indeed provide a plan view akin to the three bladed propeller of one of the many piston-engined aircraft to be seen in the skies in the first half of the last century. That much I knew of it from an early date of our moving to Amersham in the early 1990s.

By then I was already engaged in quite a different area of study. I little realised how Amersham would come to play a part in it. One of my uncles, my father’s brother-in-law, had died in Japanese captivity in February 1945. Little was known of Uncle Charlie’s war years and of his final months, except that he was then serving as an MT driver on 84 Squadron. I was determined to discover more. One document which I acquired early on in this research project was a detailed account of 84 Squadron’s history during the early months of 1942, focusing particularly on a period in the middle of February when the Squadron was holding out against Japanese advances southwards through Java which followed the capitulation of Singapore. It makes intense reading and one wondered at the calm of the person on the spot who wrote it – the then Squadron Adjutant, a Flight Lieutenant B. Ashmole.

I went on to meet survivors of that time and hear of others, many of whom, including Ashmole himself as I later learned, were evacuated by sea to India. Some, including my uncle, were not so lucky. When he learned that I was from Amersham, Wing Commander Arthur Gill, the man who inherited the command of the squadron when it was reformed in India, from where it continued to battle on, asked me if I knew of a house called High and Over which had been first built and owned by his good friend Professor Bernard Ashmole who had served with him as Adjutant on 84 Squadron during the war. To say I was flabbergasted is an understatement. Arthur went on to tell me more about his friend and how he himself had visited High and Over more than once. Quite fortuitously part of the house was for sale at the time and I was able to send Arthur a set of the estate agent’s literature about the house ‘for old times sake.’

As I continued my research about my uncle to completion, interest in High and Over was in abeyance. Then later, again quite fortuitously, my wife, Jo, came across a book in Great Missenden library entitled “Bernard Ashmole – ‘One Man in his Time’ – An Autobiography”. It was quite a find and I was delighted to learn that copies were still available; advice which I passed on to several other parties whom I thought might be interested. The book, which was published posthumously in 1994, is an absorbing goldmine of information – about the house – about its first owners and occupants – and about the life and times of a man who deserves some mention in the chronicles of our town, Bernard Ashmole himself. The book also furnished such information as enabled me to establish contact with first his son, Philip, and then his two daughters, Stella and Silvia all of whom added to my stock of knowledge. His son, Philip, is a distinguished zoologist specialising in the field of ornithology, his elder daughter, Stella, became a child psychiatrist, his younger daughter, Silvia became a professional ballet dancer.

My final stroke of luck was in late 2005 when I had a phone call from a friend in the south of France, himself a competent local historian, to tell me that he had just read an article about High and Over in the Marseilles edition of The Times. I found it in the UK issue. It was prompted by the fact that part of the house was again for sale and gave a potted history of the house as well as detail of the present vendors, whose interest in restoring the house to what it was is well evidenced in the article. I wrote to them straightway explaining my interest and its origins and asked if Jo and I might have the privilege of seeing the interior before it changed hands again. We were most grateful that Mr Halley acquiesced to our request and I am pleased to say that we have now enjoyed the spectacular view of the Misbourne valley from the canopied upper level of High and Over.

But to the detail…..Professor Bernard Ashmole’s distinguished life is encapsulated in no less an authority than “Who Was Who”. He was born in 1894. He served in WW1 being severely wounded during the battle of the Somme and was awarded the MC. After that war he graduated in classical archaeology from Oxford and went on to several appointments including positions in Greece and Rome from whence he returned in 1928 having accepted the post at the University College of London. In 1939 he became Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum which was timely because, at the outbreak of WW2 and before joining the Royal Air Force, he provided for the safe keeping of such treasures as the Elgin Marbles. During the conflict he served in the Middle and Far East where he just managed to avoid being taken by the Japanese. Later, during the period of the attacks from V1 and V2 rockets, he contributed to staffing the Air Defence of Great Britain. He rose to the rank of Wing Commander. After the war he added to the accolade of academic distinctions and was awarded the CBE. He died in 1988 leaving his wife, Dorothy, a son and two daughters.

It was his move to a position in London in the late 1920s which prompted the purchase of land in Amersham on which to build his future home. His wife bought the site when the Shardeloes estate was sold off in 1928. I was later informed that it was Dorothy who also christened it “High and Over”, the name of a hill near Alfriston in Sussex where her family would go for walks. His architect had been a student of his in Rome and who shared Ashmole’s delight in Mediterranean style architecture. So unlike was its plan from anything else on the landscape at that time that both the public and the district planners were heatedly opposed to it. When one recalls that the site was otherwise then isolated and questions of interference with the interests of other property owners did not arise, one realises how the bases for objection have changed. But Ashmole’s determination prevailed even to overcoming a refusal to pipe sufficient water to fill his intended outdoor circular swimming pool. He sank an artesian well and had his own water tower. The tower has not survived but the pool has remained in use to the present day.

Even disregarding the partition of the house into two separate dwellings (they have since been reunited into one ownership), which has of course had enormous consequences, the property is much more modestly proportioned than photographs of its exterior elevations suggest, an illusion no doubt created by its bold perpendicular and longer horizontal lines. The exterior of the house seems in extremely good order, its pure white gleaming as cheerfully as it had in its early years. Inside, smaller rooms have been spawned from their larger originals and the partitions between the two halves have altered the natural lighting considerably. But the owners of the part we visited had done much to re-create the interior of the house as it once must have been, demonstrating comprehensive knowledge of its history. The gold leaf of the walls of the dining room is spectacular whilst the extensive array of their collection of original art deco furnishings and artefacts adds to the appeal of the interior as a whole. The views from the open canopied upper third floor are, despite the height attained by the trees which now surround the site, dramatic, embracing Shardeloes, St Mary’s Church and the water tower at Coleshill in one fell swoop. It has perhaps become a pity as well as a paradox that the reverse view towards the house from the valley is now obscure, for what was once seen as an intrusion would surely now be something to draw the eye. We have to be indebted to Mr Halley for promoting English Heritage’s greater concern to protect the house from further ravages and investing their own resources, energy and knowledge into re-creating that spirit of place which both it and its creators deserve.

It has also been in the house’s interests that it earned favourable comment from Pevsner and that its bold reminders of the glories of the moderne style and art deco have attracted media interest. Monsieur Hercule Poirot has visited there, as has the TV presenter, Dan Cruikshank. So too did it invite John Betjeman’s melodramatic support…… ‘I am the home of a twentieth-century family, it proclaimed, ‘that loves air and sunlight and open country’.

It started a style called Moderne – perhaps rather old fashioned today. And one day, poor thing, it woke up and found developers in its back garden. Good-bye, High hopes and Over confidence — In fact, it’s probably good-bye England. But, as we now know, ‘High and Over’ is a survivor.

In the first part of this article you were introduced to the house and Professor Bernard Ashmole, the man who had it built. But what of the survivors of the beginnings of High and Over and its early years? When the house was built between 1929 and 1931 the eldest child, Stella, would have been only six or so but it took several years more to give pattern to the garden which was worked on, as we are told, by the Professor himself together with one paid gardener and the help of several friends.

Although others have questioned the story, Stella has confirmed that during the war the authorities required the house to be camouflaged. Either its shape or its bold white surfaces were perhaps thought to be a useful navigation aid to enemy bombers. It seems that the much smaller Coombe Hill monument was also camouflaged, no doubt for similar explanation But I cannot resist the temptation to include here a reference to the finding of a German parachute in a field ‘near Amersham’ in October 1940 and which was thought to have been that of a German agent of Dutch origin who was tracked down in Cambridge and, aware of his discovery, took his own life before he could do much mischief. One wonders if the camouflaging of useful aids marking possible dropping zones was the reason.

Readers may be interested in what Professor Ashmole’s children remember of their time at High and Over. First we hear from Philip……“I went to a kindergarten in Amersham Old Town, probably from late 1937 until late 1939, but then went to Gayhurst School in Gerrards Cross from late 1939 (I think) until 1947, where the joint headmaster was one of my parents’ close friends from first war times, Pat Campbell. I lodged with his family (wife Camilla and three boys around my age) during the week and came back to High and Over for weekends. I’m pretty sure that High and Over was never camouflaged, though it got pretty shabby. But the plate glass (later Perspex) windows, and especially the glass spiral staircase, presented major problems for blackout, and we had elaborate plywood screens to put up every night. My mother had a house-full during much of the war, not only with family but sometimes also assorted relatives and friends from London.“

“My wife Myrtle and I visited H & O several years ago and had a look around part of the house with one of the then owners. It is sad in some ways, but still retains a lot of character. Yes, I suppose that “moderne” look does look a bit old-fashioned now. But I guess this is because it never really took hold in Britain, perhaps because it really is more suited to Mediterranean bright light and sunshine than to our subtler climate. I don’t think H & O would look old-fashioned in the Med, even now. Our house here, which is a stone cottage extended in Norwegian log, echoes the Y-shape of H & O, which is a lovely and underused house plan well suited to generating sun-traps on the south aspect.“

“You ask about family events at St Mary’s in Amersham. I am almost certain that Stella (Ring) was married there, although my memory is clearer of the reception at H & O; this was to a fellow medical student and happened while my father was still abroad. They had four children.“

Stella recalls………“High and Over was indeed camouflaged during the war. Professor Ashmole objected saying it was the shape of the house rather than its colour which would make it easily identifiable. In its shroud of conventional green and brown camouflage colouring it looked hideous.”

“During the early construction of the house the family stayed at the Crown. They moved in before it was finished and with scaffolding still in place. The family with ‘volunteer’ friends spent a long time clearing the land of flint by hand. The garden was very slow to develop.

The children lived virtually a separate existence in the upstairs nursery, coming downstairs just for tea or special occasions. The facilities included a small room for the governess. The patio area had a sand pit and little gardens were created at the foot of the columns. Sometimes the family would sleep out on the patio. Their father had acquired some bunk beds which had been used in an airship and sheets and blankets bought as hotel surpluses. The Professor was a genius at ‘finding‘ things.” “The servants quarters accessed by back stairs were minute. Life was very much to the upstairs/downstairs model of Victorian England, with complete homage to the class structure. There was a large kitchen equipped with what were then state of the art accessories – such as a refrigerator. There was also a Hoover vacuum. Central heating was coke fired.”

“Local friends were limited to professionals and others of high distinction Drs Strang, Johns and Rolt were acquaintances. Rev. Briggs was at St Mary’s but it was thought that he and Prof. Ashmole did not get on too well. During the war several people came to stay at H & O. The mothers of both parents and Sir George Hill were amongst them. So too were there two schoolgirls aged 10-11 and two secretaries, girls of 18-20 who were relocated to Amersham with their firm which had some wartime role or other. For a while the top flat was occupied by a woman from the East End with her five children. They were obviously very uncomfortable with being removed from their normal social environment – miserable, lonely and unhappy.”

Though Stella at first went to a school in Chesham Bois all three children were eventually educated at home and Stella remembers having a eurhythmic dance teacher. She adds… “Philip was born at home and because the midwife lived 20 some miles away and was out at a dinner party at the time he was delivered by his own father in the bedroom. He was referred to as the wolfling because he was always hungry.”

No one died at the house but there were two wedding receptions – one for Stella herself and one for her uncle. The ceremonies took place in St Mary’s. Silvia takes up the story….. “Our telephone number was Amersham 27”. Silvia particularly remembers this because Amersham 26 was the number of the emergency wartime Maternity Unit set up at Shardeloes. Mis-dialling would often lead to members of the Ashmole family being at the receiving end of calls from anxious expectant parents.”

Of her father, Silvia advises that despite his experiences, courage and professional standing he was overbearingly modest and unquestionably kind. With his children he was inventively playful and great fun. She recalls how during WW2 the water tower which her father had had installed was used as a look-outpost by the Home Guard who would solemnly appear on duty suitably camouflaged with vegetation for their vigil. She too recalls the finding of a parachute in nearby fields which for a while reinforced the local gossips’ notion that this strange family at High and Over were somehow in league with the enemy. She also recalls concerns at a different time that a German parachutist had found refuge in their garage. It was she herself who with some trepidation went to find it quite deserted.

Oddly enough the family did not have a car. One consequence of this and the fact of Professor Ashmole’s voluntary estrangement from the then Rector of St Mary’s meant that the children had to walk or cycle everywhere, including to Chesham Bois for Sunday services.

Silvia is among those who remain very dubious that the house was ever camouflaged and was there often enough to be positive of her conviction. So on that topic at least we must declare at best an open verdict until the case one way or the other is better proven. What happened to the children in their adult lives is another story but it seems that in their chosen professions they inherited the tireless application and dedication of their father and not a little of his extra-ordinary memory and skill in his use of good, concise, and clear English which is redolent of a time when such an asset was as entertaining as it was widely respected.

It would be rewarding to think that this article prompts some readers to learn more about High and Over and its first occupants. I can do no better than refer them to “Bernard Ashmole (1894 – 1988) An Autobiography”. It’s a gem of a book, beautifully written of course, and on lovely paper (235 pp). One chapter (of 14) is entirely dedicated to High and Over and the Thirties. There are several photographs of the house and of its first owners. Additionally the book includes a full reproduction of the article on High and Over from the Sep 1931 issue of Country Life. There are also good accounts of WW2 experiences which include that of an epic escape in an open boat from Java to Australia by members of 84 Squadron who evaded capture by the Japanese. Bernard Ashmole was not on board but it is included in the book as an entirely fitting tribute to those of his comrades who made the voyage.