This report of a talk to the Amersham Society by Janet Dineen was written by Shirley Sherlock and is reproduced here by permission.

Records show that in 1589 there was dyeing and fulling at Chesham Bois Mill. From the 1640s until 1798 spinners and weavers were mentioned and in 1789 Thomas Bailey built a cotton mill, employing many local inhabitants until 1809, sited where Tesco’s car park is now. Thereafter it was bought by William Jennings to make silk crepe until the mill closed in 1851.

The first craft explained by Janet was lace making. To be skilled in the making of lace meant that an income was assured for life, and the girl or later in marriage, woman, would not be a drain on the local community. Started by the Huguenots, the lace schools taught the young children very little other than lace making and tiny children paid a fee of about 3d. a week for training. No numeracy was included, only Bible studies and only a few could sign their names.

The first craft explained by Janet was lace making. To be skilled in the making of lace meant that an income was assured for life, and the girl or later in marriage, woman, would not be a drain on the local community. Started by the Huguenots, the lace schools taught the young children very little other than lace making and tiny children paid a fee of about 3d. a week for training. No numeracy was included, only Bible studies and only a few could sign their names.  The need for light to see the crossing threads was imperative so a special stool holding flasks filled with clear water around a single candle was used. Tiny patches of light, refracted through the flask lense, were all the lace makers had to see by on dark days. The lace makers were not allowed to have a fire because the threads had to be kept clean, untainted by soot. Instead, embers from the bakery were placed in chaddy or dicky pots beneath the lace makers ‘ stools with the added risk of setting petticoats alight.

The need for light to see the crossing threads was imperative so a special stool holding flasks filled with clear water around a single candle was used. Tiny patches of light, refracted through the flask lense, were all the lace makers had to see by on dark days. The lace makers were not allowed to have a fire because the threads had to be kept clean, untainted by soot. Instead, embers from the bakery were placed in chaddy or dicky pots beneath the lace makers ‘ stools with the added risk of setting petticoats alight.

Lace is made on a pillow with bobbins marking each thread. We saw bobbins made by the local bodgers called thumpers which were used in Amersham. Small off-cuts were used to make solid, bulky bobbins each identifiable by their different woods. There were spotted, striped and ringed bobbins. The finer bone bobbins from further north in Buckinghamshire had decorative squared-off beads at the end and are now collectors’ items for the lace makers. The lace patterns are pricked out onto thick paper. The outline edges of the lace, made from shiny threads or gimps are marked on the patterns in Indian ink. Collars, cuffs, lace edging patterns and made up lace were passed round the audience for inspection. Mrs Dineen explained that, in Victorian times, ladies often wore, pinned on their hair, a lightweight strip of lace called a lappet.

Buckinghamshire lace was fine and expensive. The makers were tied to one dealer who supplied the thread and the patterns and then sold the product. When the dealers fees had been paid the lace makers had very little from the London trade. Noted dealers in Amersham were William Stalham, 1653, Daniel Anderson, 1690, Henry Hopper, 1721, Giles Child, 1757, William Morten, 1792, James Brickwell, 1823, and Isabella Brickwell who dealt until 1830.

Black lace, known as Amersham Veil, is recorded in 1792. Making black lace really strained the eyes because the threads did not cast a contrasting shadow as they crossed over each other. Fine black lace was exported to Paris for naughty underwear. Blond lace was made in the almshouses in Amersham and sent to London for Queen Victoria’ s trousseau.

Janet Dineen explained the difference between Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire lace. This is an historical rather than a regional difference. Fine lace, called Buckinghamshire lace, could be copied by machine in Nottingham. The prices dropped and the dealers went out of business. But, by going to Malta, dealers from Bedfordshire picked up new designs that could not be copied by machine. These designs became known as Bedfordshire lace and extended traditional lace making, in both counties by fifty years.

Lace making declined when compulsory education started. By 1880 children were making very little lace and so were not acquiring the skills of fine work. The thread was thicker, the work poorer, the designs coarser and the lace did not sell, even at 6d. a yard.

By the late 1700s, at the Plait Schools the children learnt a rhyme: “Over one, under two, pull it tight and that will do.” This was the pattern for straw plaiting and it became a source of income. The straw plaiters were less well educated; few could write their own names but they were taught to count up to twenty, a score. The straw plaits were sold in twenty-yard lengths. A yard was marked on the cottage mantelpiece and the plaits were measured ready for market. Straw plaiters were not tied to one agent but sold to any agent who worked as a go-between for the hat makers of Luton. The nearer to Luton, the more popular was this cottage industry .

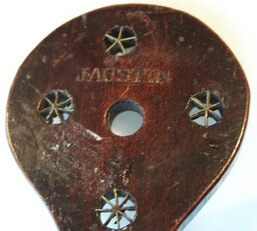

The sellers could walk to the agents at the market but this meant that they had no time for domestic work which often became a co-operative effort between neighbours. The girls making the plaits ran the straw through their mouths to dampen it and thus got sores from the sharp edges or the sulphur or urine used in treating the straw. Straw was imported from Italy so the work was not seasonal, restricted to our own harvests. It was said that lace makers had sweet lips and straw plaiters had sore lips. Whole stems of straw made thick, chunky hats when sewn together. To make finer plaits a straw splitter was invented, in Chalfont St Giles. The straws, split into six strips made a much finer plait and we were given a sharp pointed splitter and a fine hat to examine.

Straw in the Aylesbusry Vale was coloured using local Aylesbury prune juice, urine and alum. Black straw was fashionable and it was sometimes used to make patterns around the brim. Piping edging, an Amersham speciality, was made by winding straw round a whalebone mould. Purl edged plait was another local speciality and Mrs. Shrimpton, a local straw and lace bonnet maker, could copy the London bonnets of the ladies from Shardeloes. The men who had learned to plait as children made simple rustic plait. They were not as skilled as their wives but they could still supplement their low agricultural wages. This cottage industry died out when competition from China and Japan started about 1900. This cheap plait was imported to Luton and the more expensive local plaiting could not compete.

Amongst the huge display of crafts that Janet brought with her were two small chairs. One seat was woven rushes and the other was cane. The rushes were prepared by soaking them in the village’ s dirty horse pond. The rush seats for the chairs, mainly for the church, were made by the men because the work was so dirty. The women did the caning, often sitting on the doorstep because of the better light. The more complex the pattern the higher the piece rate. The children were also involved, they collected the chair seats and delivered the finished articles. There were chair makers in Whielden Street in the 1820s and the Hatch family worked there from 1845 until the 1920s.

Finally we looked at embroidery, which included decorative beading. Holmer Green became a centre for this work through the encouragement of Mrs King from Little Missenden. She walked from her home to Holmer Green and acted as the agent for the village. The beading went to London’s East End. Norman Hartnell bought beading for the Queen Mother’s dresses. When debutantes “came out” their ball gowns were adorned with this beading but that market has now been replaced by the demand for beaded wedding gowns in Greece.

Over the last 80 years Holmer Green’s skilled workers have gone through several phases of embroidery work, and Janet had learned much from their historic craftwork. Originally they made “frogging” to hold the necks of cloaks together. This was embroidery with cord which was symmetrical about a button and a loop, again fashionable on the cocktail jackets of the 1950s. Beading work followed by “tambour beading” became the next skills. Fine beads are threaded onto the work in a pattern. I have never seen such a fine sharp pointed needle which incorporated a tiny hook near the point. We all looked at it with some respect and care. During WWII, when resources were limited, “roulé” work was done. Thin strips of fabric were stitched, an easy job, and then more skilled workers linked the strips together with open work embroidery. This was used to decorate the fronts of blouses.