In 2014 Amersham Museum had an exhibition about the history of the Goya business:

You can also read an account of a visit to Goya’s in the 1950s at the bottom of this page.

Click on this link for a new article by Alison Bailey written for Bucks Free Press, December 2021.

This article was written by John Clutterbuck in 2013 and is published here with permission

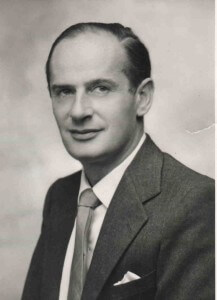

Amersham Museum has a large number of items connected with Goya, a cosmetics company which occupied Badminton Court, on the old Wellers’ brewery site in Church Street, from 1946 to 1985. Among the more comprehensive of the collections of papers, perfumes, photographs and other background material on Goya are those relating to Ernest (Ernie) Joyner, chief chemist, and Peter Meade, head of sales. Their memorabilia, together with Douglas Collins’ autobiography, provide insights into the growth and eventual decline of a company that was in many ways quintessentially British. Goya played an important part in Amersham’s Post War employment and commercial history.

In 1932, Douglas Collins, then aged 19, founded a company to make brilliantine and hair cream in Kentish Town. Four years later, after various jobs and changes of fortune, Collins decided to concentrate on making perfume. His autobiography “A Nose for Money – How to Make a Million”, was published in 1963. In it, he stated: “During 1936 I made fifteen different perfumes and began to learn something about my trade. I learned that the success of a perfume depends much more on the fragrance than on its name or the package. The best known houses with big advertising and beautiful packaging cannot sustain sales of a new perfume for more than a year or two unless enough women like it and buy it regularly.”

Collins’ company’s name was changed from Lafontaine to Goya in 1937. Collins recalled that an advertising show-card was prepared to introduce the name, showing a reclining nude. “When it was printed, no chemist would show it in his window in case his customers objected to it. I had to overprint a sort of nightdress before I could use it. I had never heard of Goya when I chose the name for my perfumes, but, oddly, this first Goya perfume colour drawing repeated the artist’s experience with his naked and clothed Maja portraits.”

The Times reported that, in 1938, Collins was discovered by beauty editors. The breakthrough … “came with an order from Woman’s Journal for 200,000 tiny samples to be given away as a circulation booster with the magazine. From then on the firm, founded on the idea of a small amount of something very good, hardly looked back.” Douglas Collins was … “an extremely successful perfumer – along with his business flair he had that rare olfactory genius which enabled him to create new scents.” The Times stated that: “nearly all the great perfumers have been French, so it was extraordinary to find this gift in a young Englishman.”

The firm continued to operate throughout the Second World War, when Collins served with the Royal Navy. An advertisement appeared in The Times for 17 October 1941: “Goodbye Paris But Goya is a luxury that is still in perfect taste”, advertising Coté face powder, Goya lipstick, and five famous perfumes: Gardenia, Studio, No. 5, English Rose and Heather. Paris had fallen in June 1940. The Times of 31 May 1945 carried an advertisement for Goya perfumes, powders and lipsticks with 151 Bond Street as Goya’s address. Somewhat to Collins’ surprise, the company not only continued in production but managed to do well in the war without him.

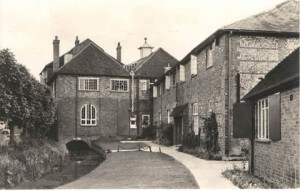

Goya initially had offices in Whitehorse Street, near Piccadilly, and a factory at Brook Mews, also in W 1. In 1940, Whitehorse Street had been bombed. The offices were moved to Brook Mews. Concern over bombing remained, and a factory employing 14 people was established over an ironmonger’s warehouse in Buckingham. As soon as Collins was discharged from the Navy in July 1945 he looked for a larger factory. He found it in Amersham in 1946, bought the freehold of the former Wellers’ brewery in Church Street, and named it Badminton Court “because it sounded aristocratic and because the main floor area had been used for badminton courts before the war.”

There was rapid expansion after the war. Collins stated “We started in 1946 with boom conditions, a seller’s market abroad and an unlimited demand for any kind of perfumery or cosmetics at home.” Within six months of Collins leaving the Navy, sales increased from £53,000 to £222,000. Sales rose to £351,000 in the following year and to £661,000 in 1951. In 1949, Goya’s main offices were moved to Amersham.

Douglas Collins and his family moved from Royal Hospital Road in Chelsea to Mill Meadow in Amersham in 1947, which is in Mill Lane near the Misbourne. The Collins family moved again in 1953 to Hawthorn Farm in Hyde Heath, near Great Missenden, which Collins bought, together with other properties and land, for £10,500. There were responsibilities for renovation of tenants’ houses on the farm. Collins put in electricity, water and sanitation. One elderly tenant said “I used to have to go out into the rain to the privy; now I ask God to bless you every time I pull the flush.”

In his book, Douglas Collins spoke of the process of making a perfume: “Perfume is comparatively simple to make and the skill lies in ability to select and reject than any knowledge in science or chemistry. At its simplest, a perfume is a mixture of a perfume compound and alcohol. Perfume compounds can be bought from essential oil distillers and blenders and from aromatic chemical manufacturers, or you can make your own by using essential oils.”

Although this version of how to create a perfume laid stress on the simplicity of the process, Douglas Collins elaborated on the skill needed to create a successful perfume by saying that it was “like a tune in the imagination… results are not achieved by long periods of scientific research – they are achieved by long periods of confused trial and error, or by occasional pieces of luck”.

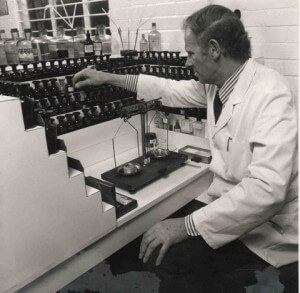

Collins described the shortest time spent making a perfume as three weeks. For this reason it was not a very good one. One of Goya’s most famous perfumes, the Black Rose, took four and a half years to produce. Black Rose was a very sophisticated perfume described as “very long lasting, but with a French rose top-note.”The perfume was formulated in the “organ” room, in which there was an array of massed ranks of ingredients known as essential oils from which new fragrance blends would be painstakingly developed. Once established, the formula was scaled up for manufacturing by Ernest Joyner in the specially built compounding laboratories, which were situated in the garden behind Badminton Court. Here the concentrated perfumes, known as compounds, were prepared for shipment to the factories.

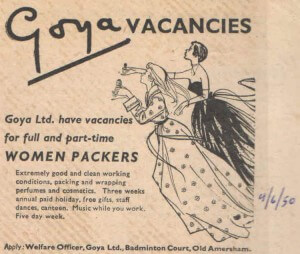

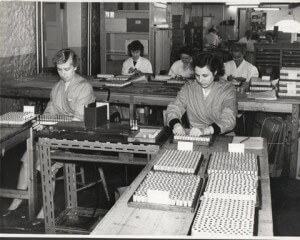

Goya perfumes were packed entirely by hand. This is said to give the best possible finish. The company employed many women in the packing department, and had an advanced employment and benefits package.

Production at the Raans Road site, Amersham, started in 1952. One of the volunteers at the Museum reports: “When I was at school, Wycombe RGS, the holiday job of choice in the early 1950s was at Goya’s at Raans Road. With luck you could get on the night shift to earn more money by working in the ladies’ powder section. The powder was so fine that it had the potential to explode, so you got danger money too. It never exploded to my knowledge.”

In October 1955, the magazine Buckinghamshire Interest carried an article entitled “Amersham Perfumes Go Around the World” – exports were important to Goya. Agents had been appointed in many countries, some of them during the war in anticipation of later supplies. For the first twenty years of Goya’s existence, its brand range was led by perfumes in tiny size bottles, together with powder, bath cubes and hand lotions.

Collins was appointed director of the National Film Corporation in 1955. He was Chairman of the film company British Lion from 1958 to 1961, when he resigned after putting it back on a sound footing. Douglas Collins’ hard work and long hours with British Lion and the National Film Corporation were unpaid. Collins was the author of the Mr Mole series of children’s books which were published from 1947 to 1951. He wrote “Sailing in Helen”. “Helen” was one of a number of boats that he owned – he had a passion for sailing.

Douglas Collins sold Goya for £1.5 million to Reckitt and Colman in 1960, buying it back for £0.8mn in 1968, without rights to trade marks outside UK, Common Market, USA and Canada. In 1965, Collins joined Sutton and Sons Ltd., the Reading based seed merchants, and took control the following year.

On 14 April 1968, the Bucks Examiner reported that, following the re-purchase, three quarters of Goya’s shares were owned by Sutton and Sons Ltd, which in turn was 75% owned by Douglas Collins and family. One quarter of Goya’s shares were held by Douglas Collins’ son Christopher. The high point for Goya traditional perfumes and cosmetics seems to have been the late 1960s and early 1970s. Production at the two Amersham sites – Badminton Court and Raans Road – was supplemented by a new factory at Rotherham.

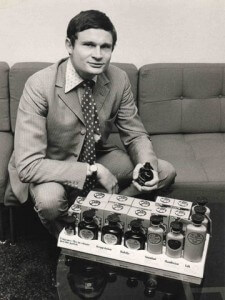

There was glamour, as shown by a photograph of Ernie Joyner with “Debbie, Miss ATV”. There was hard work as well. Among Ernie Joyner’s papers in the Museum are many pages of perfumery recipes which were developed in the Goya laboratory. There is a picture of him at work in the “organ” room, where the new fragrances were blended. Ernie Joyner’s predecessor was Monsieur Millon.

On Saturday 4 March 1972, four years after the re-purchase from Reckitts, Douglas Collins died at the age of 59. Obituaries appeared in the national press, including The Times and the Financial Times.

In 1975, Goya was sold to Imperial Chemical Industries. The Times of 5 July 1975 reported that: “ICI is to take over the Goya perfumes and toiletries range by buying the owner of the brand, D. R. Collins, for an undisclosed sum. The plan is to merge Collins and ICI’s subsidiary Avlex, which makes the Savlon range of medical products. Mr Christopher Collins will continue as managing director.” In 1976, it was reported in the Daily Mail that Christopher Collins, a leading National Hunt jockey, married in a society wedding attended by Princess Anne.

Christopher Collins was Managing Director of Goya Ltd from 1968 to 1975, and was a Director of Goya from 1975 to 1980. He represented Great Britain in 3-day equestrian events 1974-80, was a steward of the Jockey Club 1980-81, a member Horse Race Betting Levy Board 1982-84; chairman of Britain’s 3-Day Equestrian Team Selection Committee 1981-84. Christopher Collins was on the Board of Aintree Racecourse Ltd 1983-88, and of the National Stud 1986-88. He has also held directorships in major UK companies, including the Hanson Group.

There is a document in Ernie Joyner’s papers headed “Message to Employees” from C V Syms, Goya’s Chief Executive in 1982. Mr Syms reported that 1981 had been “a very difficult year”. The number of employees had been reduced from 179 in 1980 to 151 in 1981. Sales of fragrances – the company’s traditional lines – fell from £2.1 million in 1980 to £1.6 million in 1981. Sales of Savlon Liquid were over £4 million in both 1980 and 1981. Exports of all products were nearly a tenth of total sales.

In 1979, Savlon accounted for two thirds of Goya’s sales, and fragrances for the remaining third. By 1981, Savlon provided 72% of sales, with fragrances accounting for only 28%. Savlon became part of the Goya production range in 1975, at the time of the ICI takeover. In six years. Goya’s traditional fragrances had fallen from 100% of sales to little more than a quarter. By 1981, as reported by Mr Syms, Goya was barely profitable. Following the sale in 1984 of Goya to Beauty International by ICI, the company closed down. By 1988, Badminton Court had been converted to apartments and offices.

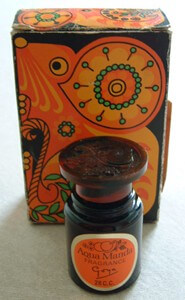

Nearly thirty years after Goya’s closure, the Aqua Manda brand still has resonance. Since 2008 there has been a campaign on facebook, backed by “thousands of messages”, to bring back Aqua Manda, a Goya perfume launched in the 1960s. According to one of the contributors to the facebook campaign, “Aqua Manda sold 20,000 bottles of perfume per year between 1965 and 1973”. The following entry has appeared on facebook:

Nearly thirty years after Goya’s closure, the Aqua Manda brand still has resonance. Since 2008 there has been a campaign on facebook, backed by “thousands of messages”, to bring back Aqua Manda, a Goya perfume launched in the 1960s. According to one of the contributors to the facebook campaign, “Aqua Manda sold 20,000 bottles of perfume per year between 1965 and 1973”. The following entry has appeared on facebook:

“Beauty Brand Development (Westex) are bringing back a famous 70s iconic perfume Aqua Manda. The original scent of mandarin and spice will be back in department stores and online by the end of 2013; we are also launching a fragranced talc and soap.”

This article was written by Eustace Alliott about a visit in the 1950s

Goya had very kindly given me permission to take some colour photographs in their cosmetics factory and on arrival I was met by Mr. Timothy Collins and Mr. Barnes, the Works Manager. Their Badminton Court Factory is housed in the 17th and 18th century buildings which once formed Wellers’ Brewery – the name Badminton Court comes from the fact that after brewing ceased the large Brew House was used by a Badminton Club. The firm came to Amersham from Buckingham soon after the end of the war in order to secure larger premises. The old Brew House has now been divided into a ground floor and upper floor but the old roof timbers can still be seen. It was to this upper portion that Mr.Barnes took me to show me what they were doing.

Our first call was at the lipstick moulding section in a corner of the great upper room. Here several girls in colourful red overalls were attending to the Moulding machines. The colourful overalls, by the by, were not worn for effect, but as a precaution against lipstick stains and expensive laundering.

The process was that the lipstick material was manufactured in their Raans Road Works and brought down to Badminton Court. Here it was warmed and melted in water-jacketed vessels and brought to a pre-determined temperature for a pre-determined time. It was then poured into the moulds which appeared to form six dozen or so lipsticks at a time. These moulds also were water-jacketed and when the moulds were full, cooling water was run through the jackets in order to set the sticks. The lids were then traversed from side to side to remove the “flashing” and after that magazines of lipstick cases were fixed on the moulds and the sticks were forced up mechanically into them and collected. They were taken to a nearby table where two more girls looked them over and removed any remaining “flash” and put them into carrying boxes containing some dozens.

At this stage the sticks were in their cases but were still uncapped. They were now taken to another department where a number of girls working at a wide table with plenty of north light, capped them and checked them, removing any further “flash” that might occur. The cases were now returned to the large room and were placed at the top of a long slowly moving conveyor, while girls on either side now in white overalls, packed them into cartons containing one or three lipsticks. The packed cartons were returned to the conveyor and as they came towards the end, were packed into bulk cartons.

At another conveyor a number of girls, still in white, were packaging “Gift Cologne”. An automatic vacuum machine at the head of the line, appropriately supplied with scent and bottles, filled the latter and they passed on to the moving conveyor. As before, the girls packed them into cartons singly and then in boxes for storage purposes. This upper floor in this ancient but modernised building was brightly lit both by daylight and by neon lighting and the working conditions seemed both healthy and pleasant.

From viewing the bottling and packaging of the “Gift Cologne” we passed outside the building to enter another much smaller one in the grounds, where we found the river Misbourne flowing quietly between walls, with the Church precincts on the other side. Entering the perfume house we were met by the Perfumer, who explained briefly what was done there. They have a store of over 200 different kinds of essential oils, which provide the perfume. A selection of these, according to the perfume required, is mixed and added to a fixative, such as ambergris, which has the property of holding the perfume, increasing its durability. This mixture is left for some time at full strength, in order to mature, and then is diluted to the required extent with spirit. This again is left for a time to mature, and then is cooled by refrigeration in order to cause the various waxes to condense out of the liquid scent so that they may be filtered out. The reason for this is that failing this operation, these substances would later condense when the scent is in the bottle and would cause it to become cloudy, or might form a deposit. The scent is filtered by gravity through batteries of asbestos disks, and is run into a carboy from which at a later stage it will be dispensed into bottling machines.

Later in the afternoon I was able to visit Goya’s Factory at Raans Road, on the “Hill”. The manager, Mr.Cole, commenced at the powder mixing department. Here, in a dusty atmosphere, a number of great machines were mixing talcum or face powder. They worked mainly automatically and required comparatively little labour, though a man in dusty overalls was in attendance – suitable grades of talcum powder are mixed with perfume, deodorants and colour to suit the market. In an adjoining small department, still rather dusty, two girls in overalls were attending an automatic vacuum machine which they supplied with empty containers, which it filled and passed on to the next department for packing.

We now went upstairs, where the departmental manager was a little nervous lest some interesting experimental apparatus in process of development might be photographed. After reassuring him on this point I was taken to the shampoo packing line. Here on a sloping conveyor lay a long polythene tube filled with liquid shampoo. This passed to an automatic machine which sealed the tube at appropriate lengths so as to form separate transparent containers filled with liquid. These being electronically sealed at both ends, were then cut apart and went elsewhere for packaging. The excess liquid was forced up into the tube, the slope of which ensured that the part being sealed was always filled with liquid. A little further on, a girl sat at another machine which was feeding “Beauty all Day” into polythene tubes. One of the most interesting lines began with a very modern automatic tube filler – a girl kept it supplied with tubes which were filled with hand cream and sealed by crimping the bottom. These tubes again dropped on to a long conveyor and were packaged by lines of white-overalled girls.

In a nearby corner of this large department were a number of mixing machines, somewhat like those used by bakers, which were mixing cream and bringing it to the right consistency. At short intervals a girl ran out from the Laboratory to take samples for testing. On a lower floor bath cubes were being made by a rotating machine having a large round hood and a number of pistons on the pattern of the tablet machines used by manufacturing chemists. This took the powder and presses it into firm cubes which it fed on to a short conveyor belt. Here another automatic machine, fed with white labels and brightly tinted foil, wrapped and labelled the cubes, which then passed on for final packaging. In the last department I visited a long line of girls were packaging “Beauty Puff” a compressed powder for compacts, which as explained to me, needs no foundation.

I think Amersham is happy to have an industry of this kind in its midst, which provides both full and part-time employment of an interesting and pleasant nature for a large number of young women, as well as for men. There seems to be a happy spirit about the place and the whole layout is a credit to the firm.