This article was written by Wendy Tibbitts for the Amersham Society/Amersham Museum newsletter and is reproduced here with permission.

During the Second World War Amersham received an influx of refugees, evacuees and displaced Londoners. Among the residents and incomers were artists, authors, musicians, and academics who seem to have formed a cultural group of enquiring minds centred on the Music Studio in Chestnut Close.

During the Second World War Amersham received an influx of refugees, evacuees and displaced Londoners. Among the residents and incomers were artists, authors, musicians, and academics who seem to have formed a cultural group of enquiring minds centred on the Music Studio in Chestnut Close.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact position of The Music Studio, because house names have been changed and new houses built. From the Kelly’s directory of 1935 we know there were six houses in Chestnut Close, but by 1939 there were eleven, this number rising to 22 by 1941. The Music Studio appears to be one of the houses built between 1935 and 1939. The actual Music room might have been a single-storey building next to the house because Mabel Brailsford describes it as having French windows and its own loft.

In 1939 Mrs Giorgia Pearce was resident at The Music Studio, and is described as a teacher of music. She was born Georgiana Wilkie Marie Hoby in 1870, in London, the daughter of a Publisher and a descendant of the Elizabethen Hobys of Bisham Abbey. She was a writer and concert pianist who also taught piano. Her only child was Stella Mary Newton OBE, who was an actress, dress historian, lecturer, and writer. Stella Newton frequently attended the Music Studio concerts and on at least one occasion gave a recitation. It is not known when Giorgia Pearce left Amersham but she was known to have been living with her daughter and son-in-law in Islington from 1954, where she died in 1963.

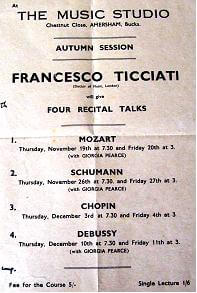

Mrs Pearce’s lodger at the Music Studio was Dr Francesco Ticciati, a composer, concert pianist, lecturer, and piano teacher. He was born in Italy in 1894 and came to London as a music student. He lived in Maida Vale until 1939 and moved to Amersham where he was billeted with Mr Darvill at Flint House, Woodside Road, until moving into the Music Studio around 1941. He died there in 1949. Francesco Ticciati had a brief obituary in the Musical Times. [See below for more information about Francesco Ticciati.]

Dr Ticciati’s great-grandson is Robin Ticciati, the Glyndebourne conductor who made his Proms conducting debut on 31st August 2010 at the age of 27.

The Museum’s research into the Music Studio has been prompted by leaflets found inside Mabel Brailsford’s wartime diaries which are in the Amersham Museum archives. The following information about the Music Studio between 1941 and 1943 is extracted from these diaries. (The diary was published by Amersham Museum in 2016.)

The Music Studio, as well as being a centre for teaching music, also organised classical concerts, and musical talks. Around March 1942 Dr Ticciati gave a series of recital talks on Beethoven. On the last Sunday of each month there was what Mabel Brailsford calls, a “literary-philosophical-religious” meeting, and she said that “the discussions following are generally the best part”.

On the 31 August 1942 Mabel recalls there being “a tiny group of friends assembled in the evening to read ‘As You Like It’”, and in September 1942 her own brother, H.N. Brailsford, a noted writer, journalist and broadcaster, came from London to talk on “Gerrard Winstanley: The Light shining in Buckinghamshire”.

Other talks were given by the Rev. R. Gordon Milburn, MA, who lived at Durris, Stubbs Wood. He was an authority on Indian Scriptures, but his talk, in March 1942, was on his ideas of how religion should help to build the new world after the War. In July 1942 the Rev. Milburn gave a similar talk called “Reconstruction”, in which he set out a proposal for a super-Church after the war, to unite all God-fearing people irrespective of creed. At this talk was an evacuee who was billeted with Rev. Milburn. His name was Elias Canetti who went on to win the Nobel prize for Literature in 1981. Canetti wrote about his four-year stay in Amersham in his book ‘Party in the Blitz’. In 1943 at least two of the speakers were non-local friends of Ticciati’s. Dr Victor Grove gave a talk on China, and Mr Kenning, a parson in the Church of England, gave an address which Mabel Brailsford said “could in part have come from a Methodist pulpit”

Some the singers and musicians who took part in the concerts were students or friends of Mrs Pearce and Dr Ticciati. Frieda Danziger was a classical singer who was billeted at Flint House, Woodside Road; and the Spanish violinist Angel Grande visited from London. Hendra Porges-Lilienfeld, a mezzo-soprano, frequently performed in the concerts.

Mabel Brailsford, a pianist herself, describes the Music Studio as “changing her whole world”. She would make the journey from London Road, Old Amersham, to Chestnut Close; pushing her bicycle up Station Road and riding back in the black-out. When there wasn’t a concert or a talk she had an Italian lesson from Ticciati, or just generally helped out when either Ticciati or Mrs Pearce were unwell. Not only did she describe Ticciati’s music as “never in my life at any concert have I heard such playing”, but appears to have found the cross-section of people she met there stimulating and fascinating.

Does any one have any memories of the Music Studio? The Museum is collecting stories of life in war-time Amersham and would be glad to receive any memories of people or events to add to the collection.

In response to that request, we received this from Leo Black in 2013:

“I spent the war years in Amersham and was very interested to come across your feature on the Music Studio in Chestnut Close, since it was somewhere I visited a lot, and where I and my elder brother received a few singing lessons from Mrs. Pearce.

If it would interest your readers to have extra information about the pianist Francesco Ticciati: as well as his concerts and lectures at the studio he used every Sunday night to play at the house of my parents, Charles and Phyllis Black, who lived it 53 Woodside Road. His Bechstein pianos, formerly the property of the great Artur Schnabel, found a home there. I was too young to stay up for the recitals but my father would always make a list of the pieces Francesco had played and leave it on my bed for me to find in the morning. (Of course I listened until I fell asleep!). In my opinion, apart from being a major influence in my development into a musician whose career took me up to Executive Producer, BBC Radio Music, he was in his own right a major pianist who reflected the wonderful influence of his great teacher Busoni. At 80 I am still proud to have been inducted into music by this extraordinary musician, Italian patriot and stout opponent of Mussolini’s fascism. (That was the basis of my parents’ friendship with him, that and a shared love of music).

I remember Francesco (always known to us as ‘Uncle Francesco’, or simply Uncle) as the kindest of men, who would practise the piano regardless of the fact that our black-and-white cat Sooty was seated on his lap – and also regardless of the fact that our neighbour Mrs. East might have been banging on the wall in protest at the noise. He may not even have been aware, since my parents did a good job of keeping the peace. Once, in a ‘rudiments’ lesson, he told me “If you get that wrong I shall have to punish you”, but even at the time I didn’t believe it.

Another visitor to 53 Woodside Road was the singing teacher Manlio di Veroli, who a few years later became famous for his training of Harry Secombe’s natural tenor voice. He and Francesco had stentorian sessions in our front room, but I’ve no idea what the repertoire was.

My early fascination with music came from predominantly from overhearing Francesco. By the age of six I was showing enough interest in the piano for my parents to decide it was time I learned to play. The chosen teacher, Constance Dupré, was a pupil of Francesco. And here there was a fateful surprise. For some reason I imagined a piano teacher as a grey, severe elderly lady; on the Sunday morning in question I was told that Miss Dupré had arrived, and made a tremulous entry into the sitting-room. There at the piano sat a definitely young person, whom even my six-year-old eye could diagnose as distinctly pretty. The light of a fine summer morning added to the effect, nor did her manner put me off. Who knows what lifelong precedents and norms established themselves in that brief moment of epiphany during the summer of 1938?”

Another comment came from Nicky Sowell:

“My grandmother’s cousin was Constance Dupré who lived at Roslea, 23 Parkfield Avenue with her parents, Frank Dupré and Florence Daniels. She was an accomplished concert musician and had studied piano and violin. Apparently Francesco wanted to marry Connie but her strict father Frank (a bowler-hatted city gent) forbade it as Francesco was Italian and it was wartime. Connie never married but died a spinster. I have in my possession many beautifully bound classical piano music books given to her each year by her parents for Christmas in the years around 1929-32. Even more interesting: I have a special Bechstein Picture Book limited published in 1927, dedicated to Francesco Ticciati and given to Connie by the pianist. It contains the photo of him shown here.”