By Alison Bailey

In March 1824 Captain Thomas Tyrwhitt Drake, MP, presented parliament with a petition for the abolition of colonial slavery from his Amersham constituency. This was an unusual occurrence as Squire Drake was not known for challenging the status quo. He had a poor attendance record in the House of Commons. When he turned up to vote, he invariably voted with the traditional Tory establishment, against Catholic relief in 1821, and against Irish enfranchisement in 1825.

The British government had abolished the slave trade in 1807, however over 700,000 slaves remained in horrendous conditions in the colonies. Mass petitions were a key strategy of the rejuvenated anti-slavery movement. 777 petitions were presented to parliament in 1823, but between 1828 and 1830, 5000 petitions were presented including another one from Amersham.

The Amersham petitions are important evidence of our local anti-slavery movement. This was a grass roots organization particularly strong amongst the Quaker community and other non-conformist church groups. Women’s societies would have held tea parties and sewing circles to fundraise and discuss slavery. This same model was adopted years later by suffrage groups in the campaign for Women’s enfranchisement. The anti-slavery network played a vital role in the moral crusade to inform people of the realities of slavery and to counteract the powerful pro-slavery lobby. The Literary Committee of the West Indies Interest (the powerful pro-slavery group) had an annual budget of £20,000 (about £1.2 million in modern money) to spend on influential articles, cartoons, and pamphlets. Cartoons depicted abolitionists as mad fanatics; a strategy later copied by anti-suffrage campaigners. This propaganda presented a rose-tinted vision of life in the colonies of well-fed slaves working cheerfully for benevolent Plantation owners. An early example of fake news!

Inspiring women were particularly important in the abolitionist movement. Elizabeth Heyrick, a Quaker from Leicester initiated a boycott of West Indian sugar and wrote influential pamphlets which sold thousands of copies in Britain and the USA. At a time when women had no voice in politics, she threatened to withdraw funding for the Anti-Slavery Society if the leadership, particularly William Wilberforce, did not drop its gradualist approach and demand immediate abolition. This was a serious threat as the network of ladies’ associations supplied over a fifth of all donations to central funds.

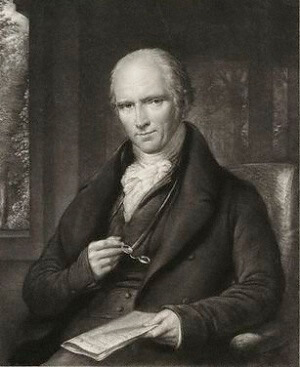

William Wilberforce’s sister, Sarah, was married to his friend, James Stephen (1758-1832), a successful barrister, and passionate abolitionist. At the age of 61, after his wife’s death, and his resignation as an MP, Stephen bought a house in Great Missenden. The name ‘Wilberforce’s walk’ was given to the terrace here to commemorate the visits of his brother-in-law.

Stephen, originally from Poole, had become committed to the cause after witnessing the brutality and injustice of slavery whilst working as a lawyer in the Caribbean. On first arriving, he witnessed the unfair trial of two slaves who were then burnt alive. He swore to devote his life to abolition. He was able to provide Wilberforce with eye-witness accounts of events in Barbados and St Kitts before returning to London with his young family to continue the campaign there. He wrote many texts including an important two volume history of the law and its practice in the British West Indies.

James’ eldest son, William, was the vicar of Bledlow for nearly 60 years. Two other sons became active campaigners. James Jnr was a civil servant in the Colonial Office and helped draft the abolition bills. He was later knighted. George took over his father’s position as solicitor to the Society. He also inherited his father’s temper and passionate nature and was opposed to the older generation’s strategy of gradualism and of persuading parliamentarians. Inspired by Elizabeth Heyrick, he campaigned for immediate abolition and formed a small working group, funded by wealthy Quakers, to instigate more direct action. He employed agents to arrange and address public meetings and to encourage press publicity. The ensuing agitation played a key role in changing public opinion and the government’s position. George Stephen was knighted in 1838 for his services.

Like his father, George was a prolific writer. His Anti-Slavery Recollections are still in print, although his contemporaries criticised him for taking all the credit for the success of the campaign. George and his wife, Henrietta had a country house at Princes Risborough before moving to Liverpool and then following their eldest son, James Wilberforce to Australia in 1855.

Following James Stephen’s death in 1832, the Missenden house was sold. In the sale particulars it was described as “a compact modern little freehold villa, with stabling, coach house garden, orchard, lawn and pastureland of about 14 acres, facing south, overlooking the village near the Church”.

In Missenden Stephen had a great influence on the young Reverend Benjamin Godwin (1785-1871). He was the Baptist Minister there from 1814 until 1822, when money problems forced him to take up a new position in Bradford.

Godwin, born in Bath, was unhappy as an apprentice cobbler and ran away to sea at the age of 15. He was later press-ganged into the British Navy, where he fought in the Napoleonic Wars. After leaving the Navy he became a Baptist Minister and teacher, initially in Dartmouth, before moving to Great Missenden with his wife, Betsy, and infant son.

In Bradford, the Godwins became active in the anti-slavery movement and invited James Stephen to give a lecture series on the topic in the Bradford Exchange. Godwin commissioned a young Quaker artist, Thomas Richmond to illustrate the talk with panels showing the horrors of slavery and the benefits of the egalitarian and multiracial world that would result from its abolition.

These lectures were so successful that Godwin was invited to tour the north in 1832 and the texts were summarised in local papers and a booklet. This eventually became a bestselling book. In 1833, this success inspired George Stephen’s Agency to employ lecturers to tour the country, in a military style campaign. This was another tactic later adopted by the suffragist movement. Godwin is one of the abolitionists portrayed in Benjamin Haydon’s famous painting in the National Portrait Gallery of the 1840 Anti-Slavery Society Convention.

By 1833 parliament was more democratic following the Reform Bill of the previous year which had abolished “rotten boroughs” such as Amersham. The landowning class, the Tories, no longer held the power. The Whigs, the only party to consider slave emancipation had a majority in the Commons of 250 seats. With public opinion strongly in favour, the government was finally persuaded to act to abolish slavery in the British colonies.

Related Articles

- The Mason family of Beel House

- Weller family connections with Jamaica

- Black voices and the local anti slavery movement

Please get in touch if you can help identify James Stephen’s house in Great Missenden or can contribute further to our research.

Sources

- QuakersintheWorld.org

- Ancestry.co.uk

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Wikipedia

- The Interest, How The Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery by Michael Taylor