By Nick Gammage, June 2023

When William Shakespeare left his Stratford home and family around 1585 for a new life in the London playhouses, he could have had no idea he was setting out on one of the most iconic journeys in English history.

There is no first-hand account of that journey so we do not know the exact way he went (1). But all the evidence suggests that his route most probably took him through Tudor Chilterns villages and the Tudor market town of Amersham.

Researching that route threw up another – in many ways more intriguing – link with the Amersham area: a previously unrecorded connection between Shakespeare and Chesham Bois with the possibility he stayed at the long-lost medieval manor house Chesham Bois Manor, home to the powerful Cheyne family.

When Shakespeare (1564-1616) walked away from Stratford, aged around 21, he left behind his wife Anne (or Agnes) and their three small children. He had married Anne when he was just 18, and she was three months pregnant. He was one of a very small number of teenage bridegrooms recorded in Stratford in that time.

Recreating The Walk

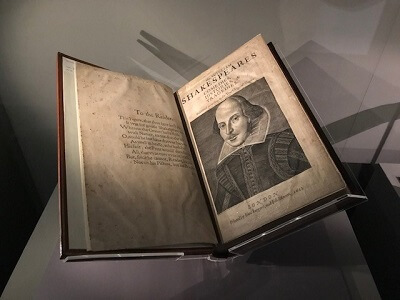

This year (2023) marks the 400th anniversary of the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays edited by his old friends and fellow actors John Heminges and Henry Condell and published in 1623, just seven years after his death. Half of the 36 plays they gathered there had never been published before – and without that book may have been lost forever.

To mark that occasion, I went back to the evidence to recreate as authentically as I could the route Shakespeare most likely followed from Stratford and in May this year, I walked it as he would have done.

There are more details of that walk here:

https://justgiving.com/fundraising/shakespearewalk

Finding unambiguous evidence about Shakespeare’s life has never been easy. Four centuries on, virtually every key aspect of that life – what he did, what he was like, what he thought, where he went – remains shrouded in mystery.

Shakespeare may be our most celebrated author, a global icon with hundreds of books about him, but he left hardly evidence of his life: no letters, no diaries, no shopping lists.

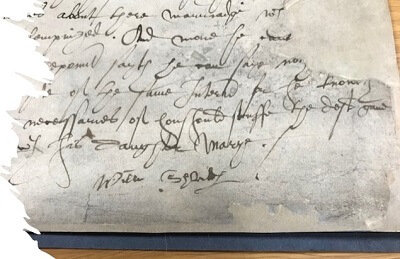

Just six examples of his signature survive and three of those are on the pages of his will. He spells his name differently each time – although that is not so unusual in an age of low literacy before dictionaries when spelling was notoriously haphazard and inconsistent.

During most of his time in London he rented lodgings so there are no documents relating to his purchase or sale of property there. He was the equivalent of an A-list celebrity with his plays performed before both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I yet there are hardly any references to him.

He seemed keen to hide his wealth. For example, In 1597 he was prosecuted for non-payment of a tax bill of just thirteen shillings and fourpence while lodging in Bishopsgate based on the value of his possessions put at just £5. Yet at the same time, back at Stratford, he was negotiating to buy New Place – one of the grandest houses in town – for what is believed to have been around £120, ten times a tradesman’s annual salary.

It is as if Shakespeare deliberately took steps to hide in London: to disappear below the radar, blend into the background, go off-grid. This makes it hard to be certain and easy to speculate.

Looking again at the evidence, there is one important source which locates him on a route which went through the middle of Amersham.

Grendon Underwood and the “Road To London”

In John Aubrey’s gossipy pen portrait of Shakespeare in Brief Lives written just 50 years or so after Shakespeare’s death Aubrey recounts being told that Shakespeare would stay overnight at The Ship Inn in Grendon Underwood on the road between Stratford and London.

“The Humour of the Constable in Midsomernight’s Dreame, he happened to take at Grendon, in Bucks (I thinke it was Midsomer night that he happened to lye there) which is the roade from London to Stratford; and there was living that Constable about 1642, when I first came to Oxon. Ben Johnson and he did gather Humours of men dayly where ever they came”.(2)

(my bold)

Now it may seem improbable to us that the country lane through this small Buckinghamshire village was “the roade from London to Stratford” in Elizabethan England. But there is a considerable amount of evidence to support this.

Aubrey’s source was the academic Josias Howe, whose father Thomas Howe had been rector of Grendon Underwood from the 1590’s until 1630, at exactly the same time that Shakespeare passed through.

There is also the evidence of a rare 17th century map.

Researching an earlier walk in 2021 I came across a modern copy of a badly damaged vellum map of 1606 showing fields in the area around Bicester, Launton and Aynho- again at the time when Shakespeare was living in London (3). What caught my eye was a northwest – southeast track across the middle of the map from Aynho/Croughton passing through Marsh Gibbon and Grendon Underwood – which was marked “London Waye.”

This was not obviously a major route between important settlements: such as between Bicester and Buckingham, Bicester and Aylesbury, Banbury and Buckingham or Banbury and Oxford. It cut across open farming country, crossing the little stream Ockley Brook and passing through a series of small villages before striking out towards Waddesdon and Aylesbury.

If the line of that route is continued northwards, the northwest – southeast line of that “London Waye” takes the traveller directly to Stratford. Here was Aubrey’s road from London to Stratford.

There is more support for Aubrey’s anecdote about Shakespeare in the North Buckinghamshire volume of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (1913) (4) The entry for Grendon Underwood (pps 130-132) sets out in detail the Tudor period details of the fine building known in 1913 as Shakespeare Farm but which was “formerly The Ship Inn”.

Wroxton Hands Fingerpost – The Way “To London”

Tracing that London Way route back from Aynho north-westwards towards Stratford, there is yet more evidence of “London Way” in the shape of the Wroxton Hands fingerpost which is positioned to the west of Wroxton on the Stratford-Banbury road at its junction with a country lane.

This 17th century guide post gets its name from the carved wooden hands which direct the traveller: “To Stratford”; “To Banbury”; “To Chiping Norton” (sic) and “To London”.

What makes that guidepost so relevant to understanding Shakespeare’s route is that the hand pointing “to London” points not along the main Stratford-Banbury road, but down the little country lane towards the village of North Newington.

That lane meets up with the ancient Salt Way, the important trade route from the salt mines of Droitwich towards Princes Risborough which had salt trading rights, and then on to London. It passes through Bodicote then through Adderbury on its way – always south eastwards – across the River Cherwell to Aynho.

The route bypassed Banbury. Walking around 20 miles a day, Shakespeare may have taken a detour into the town for refreshment or overnight accommodation but otherwise there was no reason to pass through the town.

It may seem incredible that when Shakespeare set off from Stratford around 1585 his route to London lay across open country rather than along roads linking market towns. But that would not have seemed at all strange to a traveller in Tudor England who knew too well the dire state of those roads.

Britain had been criss-crossed since Neolithic times by thousands of tracks created by people travelling long distances on foot: migrating tribes; traders; pilgrims; drovers with their herds of cattle; laden packhorses and carts. They were all looking for the safest, easiest, quickest, driest route. It is said that – before the coming of the Motorways – there was hardly a road in Britain that didn’t start life as a green lane.

Yet in Tudor England even the more important routes had decayed into an appalling condition, churned up and rutted, flooded and impassable after heavy rain, barely repaired since the departure one thousand years earlier of the Roman engineers who had built them.

These green roads often passed through rivers and streams at fording places. There were many accounts of horse riders falling into the water at times of heavy rain and drowning. In 1698 the 25-year-old Lord of the Manor of Shardeloes and Amersham MP Montague Drake was killed when he was thrown from his horse at Acton on the road home from London.

The roads linking towns in the low-lying marshy terrain around Aylesbury, Buckingham and Bicester were particularly notorious. Akeman Street between Bicester and Aylesbury was in places completely impassable in wet weather.

As late as the 18th century Daniel Defoe complained about the “badness” of the roads in the Aylesbury Vale area and the harmful impact on the national economy in his A Tour Through The Whole Island of Great Britain:

“The reason for me taking notice of this badness of the roads, through all the Midland counties, is this: that as these are counties which drive a very great trade with the City of London, and with one another, perhaps the greatest of any counties in England….”

(my bold)

It is hardly surprising that a route to London which avoided the worst of those churned-up roads developed into a popular way.

Funding Road Repairs – A Route to Heaven

For a trading nation like England, good roads were essential to the efficient movement of goods and people. By the 14th century road conditions had become so dire and trade so badly affected that priests advised the nobility, landowners, and wealthy traders that leaving money in their wills for road repairs would smooth their soul’s path to heaven.

And it is this growing trend for wealthy merchants to fund road and bridge repairs which helps solve two other mysteries about the course of Shakespeare’s journey to London.

That trail takes us to, arguably, Stratford’s second most famous son after William Shakespeare, Sir Hugh Clopton.

Sir Hugh Clopton (1440-1496), fabulously wealthy Stratford merchant elected Lord Mayor of London in 1491, lived at Clopton House, just outside Stratford. He had built for himself New Place, the second largest house in Stratford which was the grand family home bought by the increasingly wealthy William Shakespeare around 1598.

For London merchants and traders, it was critically important to their business that goods and people could move safely and efficiently and by the late 15th century that was definitely not the case around Stratford or Aylesbury.

Stratford upon Avon (from the Anglo-Saxon Strete Forde, fording place on a great road) was an ancient river crossing of the Avon. When the river was low and sluggish, all was fine. But By Tudor times the old Medieval wooden bridge across the Avon was in a terrible state of disrepair. There was a ferry but the crossing was dangerous. When the River Avon was in flood it became fiendishly difficult to cross the river.

Sir Hugh invested substantial amounts of his own money in improving matters. He paid for the great 14-arch stone bridge across the Avon which bears his name, and he funded a causeway at the western end so travellers and carts could get on to the bridge. Shakespeare would have begun his journey to London by crossing this bridge over the Avon.

But Sir Hugh was not only concerned with Stratford. He also paid to improve the road through marshy bogs on either side of Aylesbury – one of the worst sections on the route to London. Sixty-five miles from Stratford, this was clearly not an act of “local” philanthropy. Having this section in good repair was clearly of vital importance to a merchant trading between Stratford and London.

The road and bridge repairs which Sir Hugh funded were important enough to be included on the tablet commemorating his life’s work on the wall of Stratford’s magnificent Guild Chapel – which Sir Hugh also funded.

“he also made a causey (i.e., causeway) 3 miles from Aylesbury towards London and one mile on this side.”

(My Bold)

Sir Hugh funded a raised compacted embankment on the section of road between Aylesbury and where now stands Chiltern View Garden Centre on the road to Wendover. This lifted that section of road out of the sodden marsh.

And he funded a causeway running for one mile across the marsh on the other side of Aylesbury, towards Waddesdon.

The 15th century Buckinghamshire landowner Edmund Brudenell of Amersham also took an interest in improving that road. Brudenell, whose manors included Raans and Shardeloes, left 40 pounds for the repair of roads around Aylesbury. (5)

It is clear from these investments that Aylesbury was a key hub on the road between Stratford and London. It is most probable Shakespeare would have passed that way after leaving Grendon Underwood.

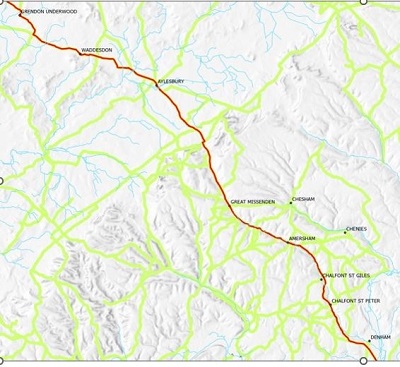

Together, the available evidence helps create a clear picture of Shakespeare’s most likely route as far as Wendover: leaving Stratford by Clopton Bridge, he would have travelled east through the rich pastures of the Felden towards the great Cotswold escarpment of Edge Hill. After climbing Edge Hill, he would have followed the road towards Banbury then, just west of Wroxton, taken the track marked “to London” through North Newington, Bodicote and Adderbury, crossing the River Cherwell by Nell Bridge on the way to Aynho.

Just to the east of Aynho he would have taken the track to Souldern (the little side road marked on John Ogilby’s 1685 strip road map of the area as “to London”). He would then have passed through Stratton Audley, Marsh Gibbon and Grendon Underwood to avoid the “ruinous” section of Akeman Street between Bicester and Aylesbury, taking the track across fields (now just a bridleway) past Oving Hill Farm to Waddesdon. Then on through Aylesbury to pass through the gap in The Chilterns at Wendover.

The Route Beyond Wendover

After Wendover, the old London road passed along the dry valley floor through the centre of Great Missenden and Little Missenden. The Black Horse on the Aylesbury Road at Great Missenden is an old drovers inn, standing by the source of the River Misbourne at Mob Well. The road through the village was important enough to be turnpiked in the 18th century to raise funds for its repair. The old toll house is still there, strategically placed by the turning into Rignall Road.

The signpost on Great Missenden High Street at the junction with Church Street leaves the traveller in no doubt about where that road through the village is heading: London.

In Tudor England, the London Road then passed through the heart of Little Missenden, making its way towards Amersham along the west bank of the River Misbourne – a track which now leads past Kennel Farms.

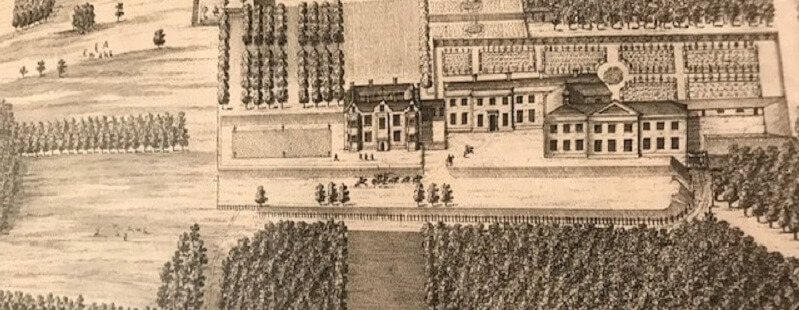

Walking with the fine chalk stream on his left, Shakespeare would have passed in front of Shardeloes, then a fine Tudor Mansion.

Owned by the Cheyne family since the 15th century, around 1590 in came into the possession of the powerful Recorder of London William Fleetwood of Missenden Abbey and then in 1595 passed to one of the six Clerks in Chancery to Elizabeth I, lawyer William Tothill.

The Drake family demolished that old house in the mid-18th and replaced it with the grand Palladian mansion which stands there today. We can however get a good idea of what that first house – the house Shakespeare passed – must have looked like from an engraving Bird’s Eye View of Shardeloes by Badeslade and Rocque from around 1739. A scarce copy of that hangs in the Tudor Room of Amersham Museum.

In the 18th century the route to London between Little Missenden and Amersham changed dramatically. In 1741, Sir William Drake, then owner of Shardeloes and responsible for its remodelling, arranged for the road to be diverted 200 yards or so up hill to the east, to enable the River Misbourne to be dammed to create the ornamental lake which now stands in front of Shardeloes.

The new road and the new lake can be seen in John Rocque’s large scale map of Berkshire of 1770.

The road towards Tudor Amersham passed in front of the main gates to Shardeloes, on along the High Street and then uphill past the mill by The Chequers Inn. John Ogilby’s Road to Buckingham map of 1675 shows that the road then passed through the centre of both Chalfont St Giles and Chalfont St Peter towards Uxbridge by way of Red Hill, crossing a river ford in the centre of Chalfont St Peters by The Greyhound.

Queen Elizabeth’s Progress Through Amersham

There is one final, important piece of evidence which further supports the idea that Shakespeare would have walked through the Missendens and Amersham. And it relates to Queen Elizabeth I herself.

For centuries English monarchs escaped the heat of London each Summer to “progress” around the country. It was an important way to be seen by their subjects in an age before mass media and most importantly it was an effective way to avoid contracting The Plague – known then as “The Pestilence” – which was at most risk of spreading in the heat of Summer.

The highest risk of contracting the disease lay in crowded places such as cities and places of entertainment. The London Theatres were often closed during the Summer months, the companies of actors went out on tour and Queen Elizabeth set out on her Royal Progress. She descended, sometimes for a month at time, on the country seats of often reluctant nobles and landed gentry who feared the high financial cost of entertaining the monarch for any length of time.

Carriages were un-sprung and the journey uncomfortable. Courtiers planning the route of the “progress” would select the safest, most convenient, and best – or, more accurately, least-worst – roads. And in 1592 that took the Queen through Amersham.

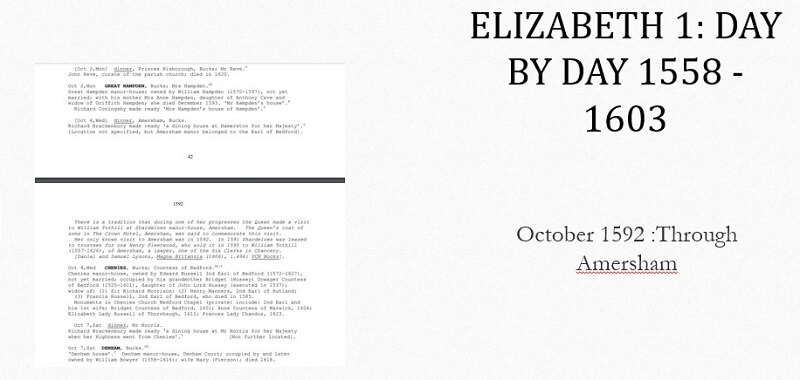

Elizabeth’s “Progresses” are a good guide to the routes other travellers would have taken around London in late Tudor England. The Court Records for those years still exist and the historian Marion E Colthorpe examined all of them to compile a detailed account of the places Elizabeth passed through, the places she stayed and the names of her hosts (6). Her work reveals that in October 1592 Elizabeth and her entourage passed through Amersham.

We can see that after staying with John Reve at Princes Risborough Parsonage she moved on to stay with “Mrs Hampden” at Hampden House and then William Hawtrey at Chequers. The entry for 4 October 1592 shows that, on that day, the Queen set off to stay with Lady Russell at Chenies and on her way dined at Amersham – or, as it is written in the records (that haphazard spelling, again): “Hamerston.”

“Richard Brackenbury made ready a dining house at Hamerston for her majesty.”

Richard Brackenbury was a senior courtier in Elizabeth’s entourage. Sadly, there is no record of which inn or private house he selected for his Queen. The South Buckinghamshire volume of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (1912) suggests the Amersham inn with the strongest Tudor pedigree at that time may well have been The King’s Arms (7)

After Uxbridge, the road passed through the still rural villages of Hillingdon, Ealing, Acton, and Shepherd’s Bush. The London Road was known on that final leg of its journey into the City of London as Uxbridge Road, the main road from the west leading through what is now the aptly named Oxford Street along Holborn – the Hollow Bourne – towards St Pauls and the City.

London had two theatres at the time Shakespeare first arrived – The Theatre and The Curtain – both recently constructed in the rural suburb of Shoreditch, to be outside the City Walls and beyond the watchful eyes of the City of London authorities.

After Holborn, Shakespeare may therefore well have turned north east towards lodgings in Shoreditch. The Globe Theatre, on the South Bank at Southwark, was not built until 1599.

There would have been no shortage of places for him to stay and no shortage of contacts with Stratford links. There were a considerable number of Stratford “emigres” living and working in the City, many known to the Shakespeare family. The Stratford carrier William Greenaway, a close neighbour of the Shakespeares, had a base at The Bell Inn in Carter Lane by St Pauls and made weekly journeys between Stratford and London carrying goods and letters. Richard Field, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s at Stratford Grammar School, moved to London as an apprentice printer, took over the business based in St Paul’s Churchyard when his master died, and in 1593 printed Shakespeare’s poem Venus and Adonis.

The Chesham Bois Connection

As well as travelling through Amersham there is a strong possibility that Shakespeare may have stayed on occasions at the medieval Chesham Bois House manor house. The evidence for this comes from his close relationship with his great literary patron Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton and Baron of Titchfield in Hampshire (1573-1624).

Wriothesley was the only person to whom Shakespeare dedicated any of his works and they were among his most important. Both of his long dramatic poems Venus and Adonis published in 1593 and The Rape of Lucrece the following year were dedicated to the dashing art-loving young Earl who was 21 in 1594 (Shakespeare was 30).

While the dedication at the start of the Venus and Adonis is stiff and formal that in Rape of Lucrece the next is something else entirely: the tone has become deeply affectionate and loving:

To the Right Honourable Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, and Baron of Titchfield

THE love I dedicate to your lordship is without end; whereof this pamphlet, without beginning, is but a superfluous moiety. The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater, my duty would show greater; meantime, as it is, it is bound to your lordship, to whom I wish long life, still lengthened with all happiness.

(My bold)

There has long been speculation that Shakespeare’s relationship with Southampton went far deeper than a platonic friendship – an idea brought to life on the screen in the scene between the two men in Kenneth Branagh’s biopic of Shakespeare in his final years, All is True (2018).

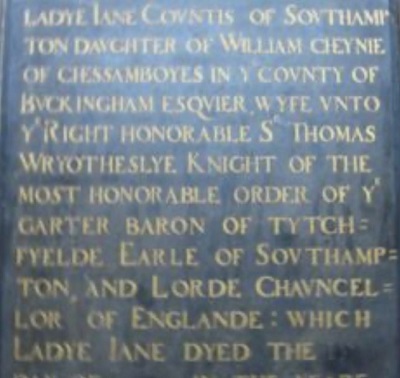

The young Earl inherited his love of learning and literature, it was said, from the great matriarch of the Wriothesley family, his well-educated, formidable grand-mother Jane, Countess of Southampton (1509-1574) wife of the First Earl of Southampton, Thomas Wriothesley. And the Countess was born Jane Cheyne of Chesham Bois (8).

Jane Cheyne (8) was daughter to William Cheyne of Chesham Bois, eldest son of John Cheyne and his wife Margaret de Louvetot who were both born around 1460. The powerful Cheyne family acquired Chesham Bois Manor in 1433, and then Shardeloes manor shortly afterwards through marriage with the Brudenells of Raans Manor.

Prominent Buckinghamshire members of the Cheyne family were arrested for Lollardy in the 15th century. But Jane, like the family of William Shakespeare’s mother Mary Arden, was a devout Catholic (9).

She was married around 1533 to Thomas Wriothesley the talented, ambitious, and ruthless courtier who was steadily gaining ever greater favour with Henry VIII. It was Henry who created him Earl of Southampton and Baron Titchfield.

The link to Chesham Bois Manor is set out clearly in the commemorative tablet on the magnificent memorial to the Southamptons in Titchfield Church. Unusually for the time, it is the effigy of a woman – Jane – which lies on top of the monument. The first second and third earls are all placed below her, clear evidence of her extraordinary influence over the family.

The inscription reads:

“Heere lyeth the Right Honorable Ladye Jane, Countis of Southampton, Daughter of William Cheynie of Chessamboyes in ye county of Buckingham Esquier, wife unto Ye Right Honorable Sr Thomas Wryotheslye….”

“Chessamboyes in Ye County of Buckingham” – the clear link to Chesham Bois and the medieval Chesham Bois Manor.

“Chessam,” “Chessum” and “Chesum” were the most common early spellings of modern-day Chesham at that time, based most probably on how it was pronounced locally. The town appears written in those variants on many maps and charts of the 17th and 18th centuries.

It is believed that Shakespeare may have been employed as a tutor to the young Henry Wriothesley and travelled extensively with him both in England and Europe. This may well have been how that strong relationship was forged.

The Cheyne family of Chesham Bois had enormous influence across Buckinghamshire. “John Cheyney Esquire of Chesham Bois” was Sheriff of Buckinghamshire in in 1566. “Francis Cheynye Esquire of Chesham Bois” held the office in both 1589 and 1603. Henry Wriothesley would have called on these powerful relations on his beloved grandmother’s side of the family at Chesham Bois Manor, as a courtesy at the very least. And William Shakespeare – good friend, companion, confidant – may well have been with him.

In the 16th century it was a legal requirement to attend church, with heavy fines for those who didn’t. While at Chesham Bois House Shakespeare would have worshipped at the attached Cheyne family chapel – which we now know as St Leonard’s Church.

With that complex mixture of Lollard and Catholic traditions in the Cheyne and Arden families we can only imagine what that service must have been like.

Conclusion

Over the 25 or so years that Shakespeare lived in London he would most likely have followed more than one route travelling to and fro between the capital and his family in Stratford. Each time the route would have depended on a number of factors: time of year, weather, business to be conducted on the way, friends to call on, state of the roads and so on. There is for example evidence of him travelling later in his career by way of The Crown Inn at Oxford to call on his friends John and Jane Davenant.

However, on that first journey – whether travelling alone or with the Stratford carrier William Greenaway for company or safety – all the evidence is that Shakespeare would have taken the established London Way through Wroxton and Aylesbury, then on through Amersham and Uxbridge.

As his fortune grew through the 1590’s he would have been able to afford the five shillings needed to hire a horse (10). But for that first journey he would most probably have been on foot. His father, John Shakespeare had recently been convicted of serious crimes, abruptly stepped down from his place on Stratford Corporation and declared himself too poor to contribute to pay poor relief in the town. It is very unlikely in those circumstances, that his son William (still living in the family home) would want to be seen able to pay the five shillings for a horse.

Together, that evidence creates a powerful image of England’s greatest writer seeing first hand and close up life in Tudor Amersham and the surrounding area.

Notes

- The designated long distance footpath Shakespeare’s Way for example created by Peter Titchmarsh describes itself as a “journey of the imagination” and does not claim to be entirely accurate.

- Brief Lives by John Aubrey (Penguin English Library, 1972)

- The copy of this field map was made by Launton historian Pat Tucker, author of Let’s Look At Launton (Launton Historical Society, 2003)

- Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (Buckinghamshire North). HMSO, 1913

- Quoted on p.10, Joan Wake: The Brudenells of Deene (Cassell, 1953)

- Marion E. Colthorpe: The Elizabethan Court Day By Day. Published online by the Folger Shakespeare Library: https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/The_Elizabethan_Court_Day_by_Day

- Royal Commission of Historical Documents (Buckinghamshire South). HMSO, 1912

- Cheyne, a common Norman family name meaning “from an oak grove” can be traced back to knights in the invasion force of 1066 and is spelled many different ways (see the Cheyne Family website here: https://sites.rootsweb.com/~cheyne/p12693.htm . I have used the simplest spelling.

- See G.P.V Akrigg: Shakespeare and The Earl of Southampton, pps 6-7. (Hamish Hamilton, 1968)

- For a fine account of Shakespeare’s journeys between Stratford and London, and the Stratford contingent in London, see James Shapiro, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (Faber, 2005)

Further Reading:

James Shapiro: 1599 – A Year In The Life of William Shakespeare (Faber, 2005)

Russell Fraser: Young Shakespeare (Columbia University Press, 1988)

Dominic Dromghoole: Will and Me (Penguin, 2007)

Julian Dutton: Shakespeare’s Journey Home (Treasurehouse Books, 2015)

Charles Nicholl: The Lodger – Shakespeare on Silver Street (Penguin, 2008)

G.P.V. Akrigg: Shakespeare and The Earl of Southampton (Hamish Hamilton, 1968)

Jonathan Bate: Soul of The Age – the Life Mind and World of William Shakespeare (Penguin, 2008)

Mary Hill Cole: The Portable Queen – Elizabeth I and The Politics of Ceremony (University of Massachusetts Press at Amherst, 1999)

Daniel Defoe: A Tour Through The Whole Island of Great Britain, 1724-26 (Penguin English Library, 1971)

Elliott Viney: The Sheriffs of Buckinghamshire (Aylesbury, 1965)

Anne Paton etc: Chesham Bois Manor, Home to the Cheyney Family for 350 years. Article in “Records of Buckinghamshire,” Vol. 50, 2010

Chesham Bois House – Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust Research and Recording Project, 2016: https://bucksgardenstrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Chesham_Bois_House.pdf