The Wellerman – Amersham’s unexpected link to whaling and the social media craze for sea shanties

by Alison Bailey (February 2021)

“Soon may the Wellerman come

To bring us sugar and tea and rum

One day, when the tonguin’ is done

We’ll take our leave and go”

You may be aware that this is the chorus of a sea shanty that recently went viral and catapulted Nathan Evans—a former postman—to the no. 1 spot in the UK charts. What you may not realise is that this 19th-century whaling song from New Zealand has its roots in Amersham and High Wycombe.

What has become a global trend started at the end of December when Nathan Evans posted a clip of himself singing the shanty on the video sharing website TikTok. The simplicity of the song and the postie’s charismatic delivery connected and ShantyTok, as it was termed, exploded. Thanks to the “duet” feature of this site others were able to join in posting videos, adding harmonies, musical instruments and even spoof versions. Celebrities such a Ronan Keating and Andrew Lloyd Webber also contributed their own accompaniments to The Wellerman and soon the national media was on to the story. After a whirlwind week, appearing on TV and radio and even on Good Morning America and ABC News, the 26-year-old from North Lanarkshire gave up his job and signed a deal with Polydor Records. As I write, this Nathan Evans’ two versions of The Wellerman, including a dance remix are at the top of the UK charts. Nathan Evans Wellerman Family Tree — shantytok mashup/supercut – YouTube

Sung by sailors over centuries, sea shanties were used to bring a ship’s crew into a common rhythm as they worked, and help them through their long, lonely voyages. It is believed that this current craze has tapped into a global need for connections and a sense of community – at a time when we are all suffering from cabin fever!

The Wellerman of the song was a supply ship belonging to the firm of Weller & Co based in Australia and New Zealand in the 1830s. What is perhaps less well known is that the money to establish the business came from the Weller Brewery in Amersham. Weller & Co was founded by Joseph Weller and his sons, Joseph, George, and Edward in Sydney in 1830. Joseph Weller was 64 when he arrived in Australia with his wife, Mary, their sons, daughters, Anne and Fanny, and daughter-in-law Eliza (who had just married George in London).

Joseph was born in High Wycombe in 1766 but most of his childhood was spent in Amersham after his father William bought into the existing brewery on Church Street and moved to the town. Joseph chose a military career first and enlisted as an officer in the Bucks yeomanry, eventually retiring as a lieutenant colonel. But in 1801, when he married Mary Brooks in Aylesbury he was working in the brewery. He was 35 years old and Mary was 22. Mary was the daughter of Joseph Brooks, a maltster and farmer. The family settled in Little Missenden and their first sons, Joseph and George were born here and baptised at St Mary’s, Amersham. The brewery was a substantial business when William died, and Joseph inherited it with two of his brothers in 1802.

Joseph Senior had been diagnosed as having consumption (tuberculosis) and was advised to move to the coast. Consequently, he decided to sell his share of the brewery to his brothers and use the money to buy a sizeable estate near Folkestone where the family moved around 1806. Unfortunately, Joseph’s poor health continued and some years later another doctor suggested a sea voyage to the warmer, drier climate of Australia. His eldest sons were sent on exploratory trips and both returned excited at the prospects offered by the new colony. Arrangements were soon made for the whole family to emigrate. Joseph Junior and Edward (who was just 14) were sent on ahead and the Kent estate was sold for a substantial sum, which according to family legend, was brought to Australia in sacks containing 12,000 sovereigns, which would have weighed just under 100kg!

On arrival in New South Wales in 1830, Joseph Senior began to invest in tracts of land from Sydney to Newcastle including extensive properties around the Maitland area, in the fertile Hunter River valley. He also bought a large home called Cleveland House in Sydney which was the family base while they investigated potential business opportunities.

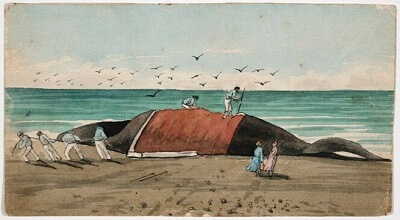

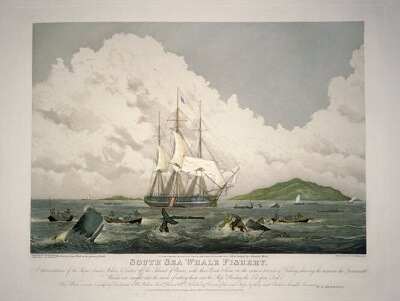

George purchased the Albion, a 479-ton vessel and started a trading business between Sydney and Tasmania. Joseph Junior saw great opportunities in neighbouring New Zealand. He started trading timber and flax in Hokianga, North Island before venturing south with a sealing expedition. He soon realised that more money could be made from whaling. There were staggering numbers of whales off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand and it was an extremely lucrative business. Whale oil lit city streets and lubricated machines in rapidly industrialising countries like Britain and America. Baleen from whale jaws also provided the ‘bones’ to stiffen corsets or was used in much the same way as plastic is now.

Joseph Junior returned to Sydney to purchase a 214-ton whaler, the Lucy Ann in August 1831. After the ship had been sold by Wellers in 1841, the writer Herman Melville became one of the Lucy Ann’s crew. Of course, his experience working on whaling ships inspired his 1851 novel Moby Dick.

George stayed in Sydney to manage the family’s business there as his wife Eliza had just given birth to their first son. But in September 1831, Joseph, and his youngest brother Edward, just 17, left with a whaling gang to establish one of the earliest whaling stations in New Zealand.

A plaque commemorates their landing point at Te Umu Kuri, Otago, an Anglicisation of Ōtākou. The point is still known as Weller’s rock and was then on the migration path of Southern Atlantic right whales. Dunedin is the closest city today and its early settlement was supported by the food produced at the Otago station.

The station was an ambitious project with over 80 buildings constructed in six months. Unfortunately, the entire enterprise was burnt down as soon as it was completed and so 1832 was a complete loss. George came over to help his brothers rebuild in time for the next season. Otago was the centre of a network of seven satellite Weller Co stations. The first shipment of 180 tons of whale oil left in November 1833 and for a few years, the business flourished.

Although profitable, whaling was perilous, requiring skill and considerable courage. Whalers chased their huge quarry in flimsy boats which were frequently smashed when the whales fought back. This sense of danger is captured in The Wellerman lyrics:

“Before the boat had hit the water

The whale’s tail came up and caught her

All hands to the side, harpooned and fought her

When she dived down low (Huh!)”

The whaling gangs were itinerant workers from all over the world and included Europeans, ex-convicts, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Whilst life on the ships was particularly harsh it was not much easier on shore. The whalers’ homes were made from whatever was at hand. Furniture was improvised, often out of the bones of whales themselves. Supply vessels were few and far between.

These shore whalers entered a Māori world. The success of a station was dependent on their relationships with the local population — in this case, Ngāi Tahu. The newcomers had to negotiate access to coastal land and resources, and this could be fraught with danger. In 1833 Edward was kidnapped by Māori and a ransom paid for his return. The next year a serious confrontation caused them to equip one of their ships (the Joseph Weller) with guns, but fortunately they were never needed. In 1835 an epidemic of measles shockingly reduced the local population who had no resistance to the virus.

At the Weller station the Ngāi Tahu and the newcomers negotiated a relationship of mutual benefit. Whaling connected the Māori to the global economy, providing new opportunities for trade, employment, and travel.

Joseph Junior died of tuberculosis in 1835 and Edward had to send his remains back to the family in a cask of rum. This meant that Edward, just 21, was the manager of the station. He still went to sea with the whaleboats (which caused George great anxiety), but he was now responsible for approximately 85 men and 11 boat crew. With their wives and children, they made up a substantial community. Many whalers had relationships with Māori women, including Edward. He married Paparu, daughter of high status Tahatu and Matua. After her early death, he married Nikuru, the daughter of the chief Taiaroa.

These mixed families were central to the success of the station. As wives and partners, Māori women produced the station’s food and supplemented the business of whaling. The Wellerman shanty’s “sugar and tea and rum” were imported as rations, however flax, potatoes, and pigs were locally produced. Any surplus was exported for profit alongside whale oil and bone. Male relations also frequently worked in the industry, either on shore or as whaling crew.

Around 1837, the whaling business in Otago began to decline. The whales learnt to adopt other migration routes, there was competition from new stations and over-exploitation led to a drop in the global price for oil. The Wellers also hit some bad luck when two of their ships were shipwrecked. The brothers decided to increase their assets by purchasing large tracts of land from Māori chiefs along the east coast of South Island, but this added to their losses when the New Zealand government refused to recognise their ownership.

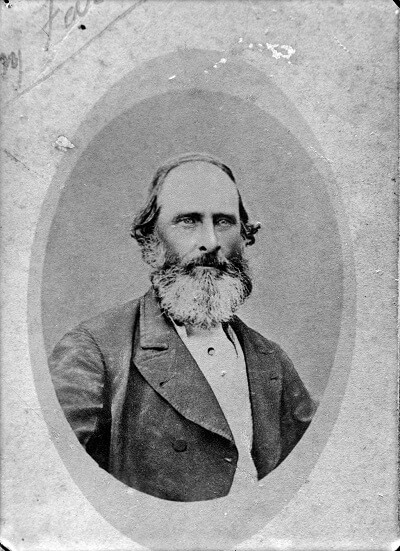

Edward’s second wife died in childbirth in 1840 and suffering from ill-health himself, he left for Sydney, handing over the running of the station to his Scottish manager, Charles Schultze. Despite selling the extensive Weller & Co assets in Australia, George and Edward were declared bankrupt in 1842. Schultze and his partner, Octavius Harwood, bought the Otago development and continued to run it as a supply station. However, Wellers stayed linked to the settlement as their sister, Anne, married Schultze in 1849 and bore him five children. Edward retained some property in Maitland where he settled into the relatively peaceful life of a landowner and farmer. He never remarried and kept in touch with his two daughters, Hana and Nani, in New Zealand. The eldest lived with him for a while but returned to Otago because she was too homesick. Nani’s son, Tom Ellison became a celebrated rugby footballer and visited his grandfather in Australia.

Edward was famously stubborn, and this obstinacy led to his death in March 1893, when Maitland suffered a huge flood. Attempts were made to persuade the 78-year-old to leave his home, but he refused. After the flood waters receded, he was discovered by a nephew drowned, trapped in his loft. A tenacious whaling captain in his day, Edward Weller may well have been the inspiration for the captain of the shanty who refused to cut the line attached to the harpooned whale.

“As far as I’ve heard, the fight’s still on;

The line’s not cut and the whale’s not gone

The Wellerman makes his a regular call

To encourage the Captain, crew, and all

Soon may the Wellerman come

To bring us sugar and tea and rum

One day, when the tonguin’ is done

We’ll take our leave and go”

Sources:

King, Alexandra, The Weller’s whaling station: the social and economic formation of an Otakou community, 1817-1850.

Blackman, Anna, Octavius Harwood, a real “Wellerman”, The Hocken Blog

Octavius Harwood – a real “Wellerman” – The Hocken Blog, University of Otago, New Zealand

https://ourarchive.otago.ac.nz/handle/10523/5533F

The true story behind the viral TikTok sea shanty hit | New Zealand | The GuardianNZ Folk Song * Soon May The Wellerman Come

Biography Joseph Weller 1 (tomswhakapapa.co.nz)

Malcolm Weller, The WELLER family tree

Entwisle, Peter (1990) Weller, Edward Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Weller, Edward – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography – Te Ara

Whaling, then and now | Te Papa