Amersham’s ‘Aliens’ – the earliest evidence of foreigners living here

by Alison Bailey

When we think about the history of immigrants in Amersham, we tend to think about the influx of refugees who arrived here after fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. Nevertheless, our area has a much longer history of incomers or ‘aliens’ as they were first recorded.

Waves of migration have always brought new people into Britain and into our area which is reflected in our local placenames. Chesham is derived from the earlier Caesteleshamm and caestel is the early word for castle, usually of Roman origin. A Roman estate ran along the river from Sarratt to Waterside and ruins were still visible in Saxon times. Ealmond was the Anglo-Saxon ruler who gave his name to Elmodesham, the early name for Amersham. Other names reflect Norman landowners who were awarded land by William the Conqueror. Adam de Shardeloes gave his name to Shardeloes manor to the west of the town and the de Bois family gave their name to the manor to the north, Chesham Bois.

Bucks Lace is one of the most obvious legacies of immigration. The lace is a Mechlin pattern (Mechelen is a town near Antwerp in Flemish Belgium) on a Lille background. Fleeing religious persecution in Europe, Huguenot lacemakers settled in the region from the 1560s. Later waves followed the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. They arrived at the invitation of local landowners such as Lord William Russell, the son of the Duke of Bedford, and George Gascoigne who had both fought for William of Orange against the Catholics.

Recording of ‘aliens’

After the Domesday records, the earliest documentary evidence of foreigners in Amersham date from the 15th century. Following the Norman invasion, migration continued from Europe on a small scale. There were numerous reasons for this including opportunities for work and trade, and after natural disasters such as the Black Death or the St Elizabeth Day Flood in Holland and Zeeland in 1421. Whilst 15th century Amersham was a small, rural town, it had a weekly market, and was relatively prosperous, thanks to the river and the fertile farmland that surrounded it. It was also a meeting point for various routes for drovers and merchants crossing the country to and from London and other market towns. This brought incomers into the town who settled here in search of new lives for themselves and their families.

In 1440 Parliament agreed that a tax should be paid by all non-native-born people residing in England over twelve years of age, the first time this kind of tax had ever been levied. Parliament had decided to introduce the tax after tensions had been growing between the native population and foreigners living and trading in England. England’s economic situation was in decline as its fortunes in the Hundred Years War with France worsened.

The rate was relatively low if you were a non-householder, such as a servant or a labourer, and slightly higher if you were a householder, such as an artisan or a tradesman. The introduction of this new tax meant that records had to be kept and ‘alien’ males counted.

15 ‘aliens’ were recorded as living in Amersham. The true number would have been higher if they had wives or children with them. If 10 of those 15 men had wives and say four children each, suddenly we could have an ‘alien’ population of 65 – around 8% of the estimated population of 800.

Amersham’s Aliens

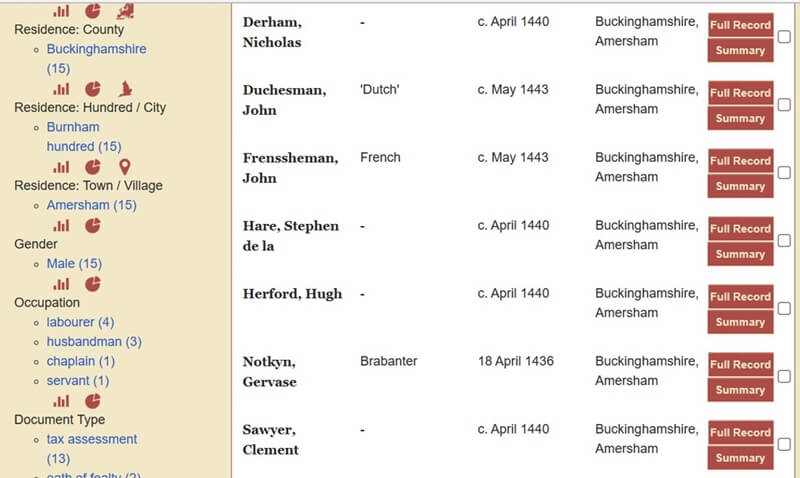

The website, England’s Immigrants 1350-1550 records the 15 men in Amersham who were documented as eligible for the new ‘alien’ tax. John van Berg and Gervase Notkyn were recorded as early as 1436 because they swore an oath of fealty – or loyalty – which was an early way of taking British citizenship. They are recorded as Brabanters which means they originally came from Flemish Belgium. John van Berg was from Vilvoorde and Gervase Notkyn from Zoutleeuw, between Ghent and Maastricht.

Labourers Peter Bartholomewe, Clement Sawyer and Henry de Beryng were listed in 1440, as were labourers ‘John Duchesman’ and ‘John Frenssheman’, although these are obviously not there actual names. ‘John’ the servant of one Bartholomew Halley also paid the lower tax.

Chaplain Nicholas Derham was a householder. Stephen de la Hare and Hugh Herford are both Frenchmen and householders. They are described as ‘husbandmen’, that is farmers with land, as are the Smyths and the Wevers (possibly brothers). They all paid the higher tax.

Amersham’s Africans

Amersham’s first record of anyone with African heritage dates from 5 June 1575. The rector at St Mary’s Amersham recorded the baptism of Ruthe of Meritania. This is believed to be the baptism of an adult woman who was converting to Christianity. It is not known if she really came from Mauritania or whether this was used as a generic term for someone from West Africa. According to Miranda Kaufman’s book Black Tudors (One World, 2017), it is most likely that Ruthe was taken from a Portuguese or Spanish slaving ship. She would have probably arrived in Amersham as a servant to one of the wealthiest families in the town with London connections. The most likely families in 1575 are the Cheyne family of Shardeloes or the Saunders family at Bury Farm.

In 1623 the Amersham parish register records the burial of Robert Hall ‘a Niger’. Again, we don’t know whether the rector used that word because of the colour of the man’s skin or whether he was from somewhere along the Niger river in West Africa. Unfortunately, there is no other evidence to provide a fuller picture of this man. With relatively common first and family names, it has not been possible to link him definitively with other events in the parish registers such as baptism, marriage or birth of children. Consequently, we don’t know whether he was a resident in Amersham or a visitor passing through. Unlike some of the entries on the 1440 tax records, he has a name so we can presume he had friends or associates in the area who knew him but unfortunately, we know more about Robert Hall, or Ruthe of Meritania.

Whilst there is evidence of black people in the area in historic pub names such as the Black Boy at St Albans and at Oving near Aylesbury, the Saracen’s Head in Whielden Street refers to the crusades. Noble English families who participated in the Crusades sometimes included a Saracen’s head in their coat of arms which led to its use as a popular pub name.