The Lost Heath

This article was researched and written by Chris Wege

Wycombe Heath was a large area of common grazing-land lying between Wycombe and Amersham – about 4,000 acres and 4 miles across. There is now little to indicate that it was ever there. In 1784 a traveller described it as: ‘The soil is various, loam, clay flints, gravel, etc. upon which grow furze, fern, brambles and trees of no value.’ The Heath was common land, providing local people with grazing for their animals, and important materials for everyday life such as firewood, bracken and furze. It was partly open land with grass, heather, bracken and gorse; partly woodland.

The woodland used to be more open and varied than it is now, with glades and scattered trees in some areas but more densely treed in others. Pigs and cattle could graze here, seeking out patches of grass and browsing young shoots on the trees and bushes. The woods were very extensive, comprising Penn Wood, Common Wood, St John’s Wood and King’s Wood – practically continuous from Wycombe to Penn Street!

Use of the Heath was restricted to people with Commoners Rights – residents of the parishes adjoining it. These Commoners were permitted to graze animals and enjoy the other benefits such as collecting certain materials. The origins of these arrangements are lost in time and may well date back to the Bronze Age when it is said that ‘cattle were king’.

Humble country people eked out a precarious existence and maintained a degree of independence with the help of the materials that they could gather on the heath. Then in the 19th Cent. all this changed, when the Heath was practically eradicated from the landscape by the Enclosures. The open heathland was turned into fields and the woodland was enclosed. The Common Rights were extinguished and many of the independent peasants were forced to become farm labourers.

However, there are still tell-tale signs in the landscape of the extent and use of the Heath and I will describe some of these under various headings.

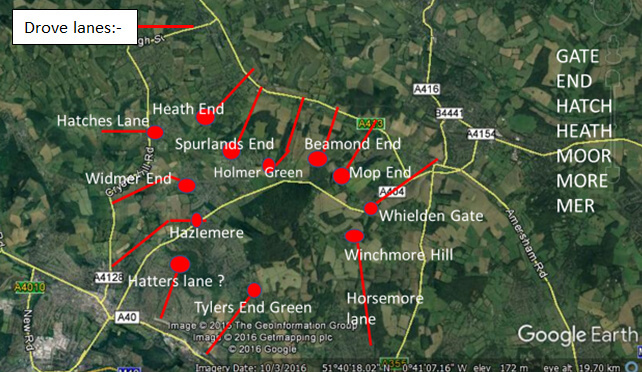

Place names. The best indicator of a settlement on the edge of common land is the name ‘End’. If you drove your cattle from your valley farm up a lane, to let the animals graze on the upland heath, you came to the end of the road and saw just rough ground ahead: the road ended. There are no less than six ‘Ends’ in the area. Then there are two ‘Hatches’ (a mediaeval word for a gate opening onto grazing land). Also, several of the local villages have names ending in ‘..moor’, ‘..more’, ‘..mere’ or ‘..mer’ – all corruptions of ‘moor’, which was the word used all over England to denote rough unenclosed grazing land. However, in the case of Winchmore Hill it is possible that the ‘..more’ had a different meaning relating to a local boundary. There is also a ‘Heath’ which is self-explanatory.

Some names have changed with time – Watchet Lane was originally Watt’s Hatch Lane; Tylers Green was originally Tylers End Green; and I speculate whether Hatters Lane, out of the Wycombe Valley, was originally a ‘Hatch’ Lane? If all these names are plotted on a map, they give a good idea of the boundary of Wycombe Heath.

Drove ways. No fewer than twenty lanes (some now surfaced roads) lead from surrounding valleys up to the high ground that was originally Wycombe Heath – often via an ‘End’. Most of these lanes had no useful function for wider travel and existed because of the need to drive cattle up to the Heath. Many of them are hollow-ways, which indicates their antiquity. These are represented on the map above as red lines. Two examples of the drove ways are shown below.

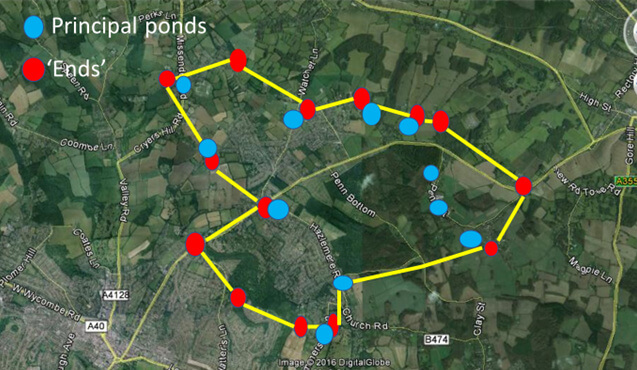

Pubs and ponds. When the cattle and their herders reached the Heath they had similar needs during the course of a long day (or, in good weather, perhaps more than one day) – namely water. The thirst of the cattle was satisfied by the existence of many ponds around the periphery of the Heath. Several of the more important ponds have survived the years but many have been lost. Of the lost ponds, traces of some can be found on the ground or on old maps, but more must have been lost without trace. The principal ponds are marked on the map below and photos of two of the ponds are shown.

Outline of the Heath (yellow lines) with ponds and ‘Ends’

In my opinion there is a co-incidence between the drove-lanes and these ponds. The ponds are usually placed at or close to the point where the lanes devolve onto the Heath. No ponds are found in the centre of the heathland area – all are on the periphery. A further co-incidence applies to the position of old pubs which are often close to the lanes and the ponds. No doubt the pubs still standing at these places are not all ancient but were perhaps preceded by beer-houses close by. The commoners, collecting furze, bracken and firewood on the Heath, together with the cattle drovers and woodsmen, comprised a substantial number of people – all needing access to drink. An example of a pub positioned for the passing trade of drovers and woodsmen must be The Griffin at Mop End (picture below), where there was only one pub and one farm – hardly providing enough trade without the passing workers.

Ancient boundaries. There are two places where the edge of the Heath and its associated woodland is still marked by an old boundary bank: at Common Wood and at King’s Wood – marked in red on the map below.

Relics of the heath. If you stand in the doorway of the Red Lion at Tylers Green and look across the road, you see Widmer Pond and beyond it a part of the Common. This would have been an edge piece of Wycombe Heath – surviving with its essential pond.

The same can be seen at Great Kingshill where another Red Lion looks out onto the Common, with Hatches Lane behind and Cockpit Hole pond a few hundred yards away. At Holmer Green the Bat and Ball looks out onto another relic of the Heath – now the Green – with a ‘lost’ pond 20 yards away and Holmer Pond, still existing nearby. At Winchmore Hill the Common remains as a relic of the Heath with a lost pond on the Common and Horsemore Pond a couple of fields away at the top of Horsemore Lane.

Green Street. There is one feature of the Heath that might almost be visible from outer space! Green Street runs from Green Farm in the Hughenden Valley, up the hill to end at Hazlemere Crossroads. As with many of the lanes, there is a pub at its end (The Three Horseshoes) and there is a disused pond nearby. However, the sheer size of this lane points to it being an important drove route. It is so wide at one point that at the time of the Enclosures, hedges were planted across the lane to divide it up into small fields. Cattle could graze as they walked along a lane of this size or could be corralled for the night within it.

The name ‘Street’ is often associated with a road of Roman origin and it is possible that in the Roman era this lane was a drove from a Villa or farm in the Hughenden Valley up towards the Heath.

Green Street may also be part of a long-distance drove route from the Vale of Aylesbury via the Risborough Gap, Naphill Common, Downley Common and then on across Wycombe Heath. Amersham Common and Chorleywood Common could have continued the route towards London.

Seagraves Farm

Another of the lanes that ran up to the Heath is Fagnall Lane, which devolved onto Winchmore Hill Common. Apart from any use for cattle droving, this lane may have had a different function in Saxon and early mediaeval times. Miles Green makes a good case for Seagraves Farm having been a deer park. Deer would have been bred and kept on the land of what is now the farm – the land being surrounded by an impressive ditch and bank – still largely extant.

The Saxon nobility of London had been granted the right to chase deer in the Chilterns and Miles identifies the area for the chase as being Wycombe Heath. Deer must have been herded up Fagnall Lane to the nearest point of the Heath, which was at Winchmore Hill and then chased by the visiting nobles across the expanses of the Heath.

Bibliography

Miles Green, Records of Buckinghamshire, Vol. 53, 2013, ‘A Deer Park at Seagraves Farm, Penn.’

Miles Green, Records of Buckinghamshire, Vol. 53, 2013, ‘Wycombe Heath and the Londoner’s Chase’.