By Gwyneth Wilkie

First published in Origins, 2016, Vol 40, No. 2, Buckinghamshire Family History Society

Appeals Tribunals came into being following the introduction of conscription in January 1916.They have been in the news recently as papers from the Staffordshire Appeals Tribunal were discovered in the Records Office even though they were supposed to have been destroyed.

Before that it was thought that the only compete sets surviving were for Middlesex (MH 47 at The National Archives) and those for Peebles and Lothian at the National Archive of Scotland. The decision had been taken to preserve two sets of documents from the many in case they were ever of interest.

It may be that the WW1 centenary will bring to light other caches of documents which should not have survived.

MH 47 has recently been digitised and is searchable online. 11,307 appeals were heard and only 26 resulted in absolute exemption. 581 were conditional and a further 2,813 men were granted a temporary exemption. 577 Conscientious Objectors came before the Tribunal. The paperwork generated included the application for exemption, the notice of decision and, if the applicant wanted to take it further, the notice of appeal. Examples of these documents can be seen on TNA’s website .

MH 47 has recently been digitised and is searchable online. 11,307 appeals were heard and only 26 resulted in absolute exemption. 581 were conditional and a further 2,813 men were granted a temporary exemption. 577 Conscientious Objectors came before the Tribunal. The paperwork generated included the application for exemption, the notice of decision and, if the applicant wanted to take it further, the notice of appeal. Examples of these documents can be seen on TNA’s website .

Some interesting stories emerged. While most men’s relatives or employers were hoping their man could avoid conscription, Mrs Percival Brown was horrified by the idea. ‘I was looking forward to him joining up’, she informed the Tribunal, ‘as I have had nearly 11 years unhappiness through him.’ She was in luck: he went!

There were three levels of appeal. If the local tribunal refused exemption, the case could be taken to the County Tribunal at Aylesbury and beyond that to the Central Tribunal which sat in London.

Although the paperwork for Bucks was duly destroyed, all information is not lost, for the local newspapers reported the business of the Appeals Tribunals, perhaps as a way of increasing the pressure on men to join up rather than have their unwillingness to serve and their personal affairs made public.

I started to go through the reports of the Amersham Appeals Tribunal in the Buckinghamshire Examiner. The aim was to see if any clues would surface about the five unidentified men mentioned on the Rolls of Honour in various Amersham churches, but not on the War Memorial. Family historians from Chiltern U3A have been researching all the names from these combined sources.

At first viewed as a task, it rapidly became a fascinating insight into how the war was affecting local businesses and local people. Furthermore the year 1916 sits usefully halfway between the 1911 census and the 1921 census which we do not yet have.

I began by collecting data for a spreadsheet listing the appellant, his details, the employer or family member making the application if it was not himself, the reasons for the appeal, and the outcome, but soon abandoned the spreadsheet in favour of note-taking.

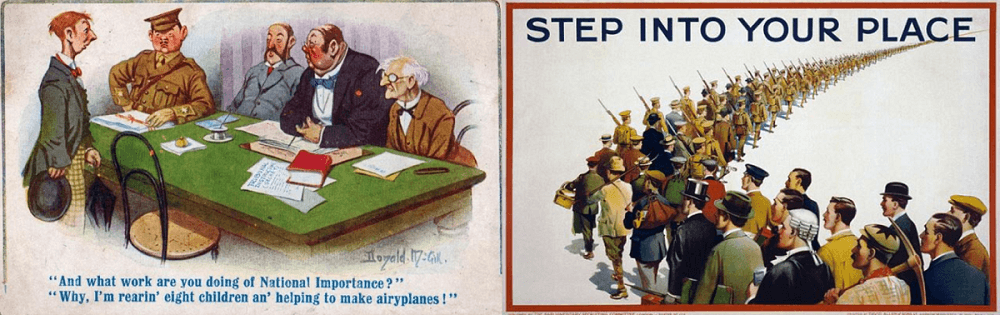

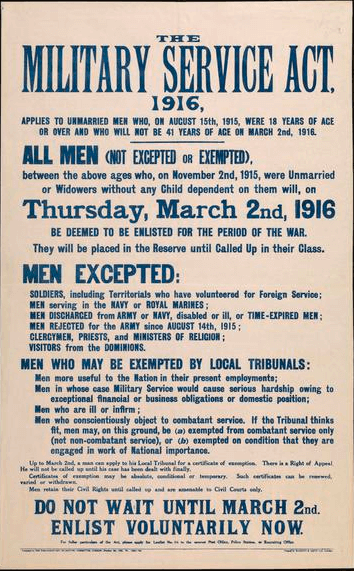

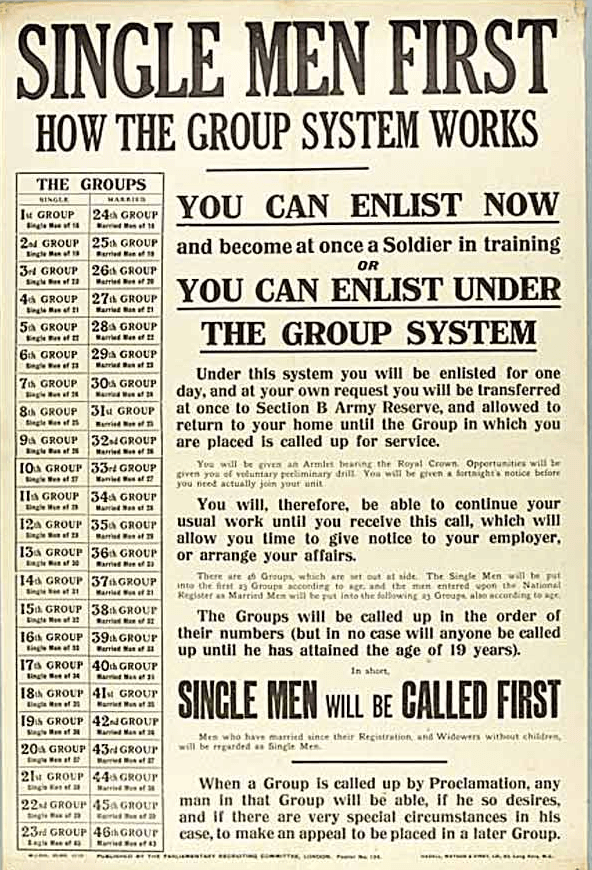

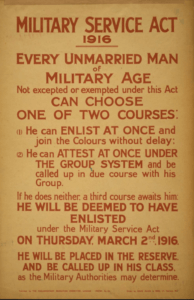

Conscription was long resisted, but by 1915 the supply of volunteers was failing to keep pace with the Army’s requirements. Lord Kitchener and Lord Derby both had some success, but while Kitchener’s appeal in May 1915 boosted recruitment by 10,000 in that month, the next month’s figures fell below average by the same number! In July the National Registration Act paved the way for the Government to record the capabilities and occupation of every man and woman aged from 15 to 65. Men in reserved occupations seen as essential to the war effort were “starred”, as were the highly skilled and those possessed of scarce skills. 1,605,629 came into that category, leaving a balance of almost 3.4 million of military age. Lord Derby as Director General of Recruiting from October 15th devised the Derby Scheme encouraging all unstarred men to attest and dividing them into 46 groups ranked in age from 18 to 41, with single and married men in separate categories, who would then be called forward group by group. Thus, while the Government tried to persuade enough men to take the preliminary steps themselves on the assurance that they would only be deployed if absolutely necessary, the data that would underpin compulsory service was put in place.

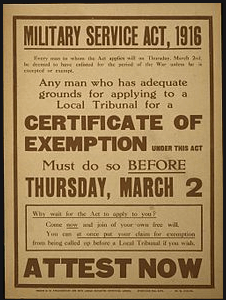

The Military Service Act bringing in conscription was passed on 27 January 1916 but did not come into force until 2 March 1916 . In the meantime the Buckinghamshire Examiner carried notices from Captain LH Green, Recruiting Organiser for Bucks, urging unattested single men of military age to “enlist now while they are free men”. While some volunteers joined up on the spot, others could make their attestation, swearing their oath of allegiance, filling in the attestation forms and probably having their medical examination. They could then return to their normal lives until called up.

The Military Service Act bringing in conscription was passed on 27 January 1916 but did not come into force until 2 March 1916 . In the meantime the Buckinghamshire Examiner carried notices from Captain LH Green, Recruiting Organiser for Bucks, urging unattested single men of military age to “enlist now while they are free men”. While some volunteers joined up on the spot, others could make their attestation, swearing their oath of allegiance, filling in the attestation forms and probably having their medical examination. They could then return to their normal lives until called up.

It is difficult to pin down the differences between being a volunteer or a conscript. Once in khaki, no difference was made. A volunteer could ask for a specific regiment and the legal sanctions that could be applied to a recruit who failed to present himself were more severe for conscripts. However, for some it was a matter of personal pride: “When conscription was introduced…it was almost a disaster to me and too many of my friends who were firmly resolved to join the armed forces as soon as we became of age. It looked as if the pride of being a volunteer was no longer attainable and that our eventual embodiment as fighting men would have no merit about it. Fortunately for us…certain regiments were permitted to accept men who offered themselves at 18.” Once attested, volunteers were issued with an armband. There were, for a while, more volunteers than armbands, but it was promised in the Buckinghamshire Examiner of 7 Jan 1916, p 8, that everyone should be supplied that week. The Recruiting Offices were apparently overwhelmed, though not in the way they might have wished: “Recruiting Officers are now inundated with applications for exemption or postponement, and all eligible men are reminded that very many more recruits are needed for immediate enlistment if the county is to maintain its reputation for leading its neighbours in this matter….We are anxious to have as few compelled men as possible from this county.”

The first session of the Amersham Appeals Tribunal took place on 3 March in the Board Room of the Amersham Union House. The composition of the Tribunal varied a little, but on 17 March consisted of Dr JB Cook (chairman), F Nash, J Hayes, W Gurney and WJ Standring (clerk). There was always a military representative, on this occasion Captain AE Hamilton-Agnew, and by the end of the year an agricultural representative, TT De Fraine, had been added. Although they met at the Union Workhouse, the area covered was not co-terminous with the Union of parishes. Cases were heard from Chesham Bois, Penn, Coleshill, Winchmore Hill and the Chalfonts, but Chesham had its own tribunal and often seems to have had a longer list than Amersham. Amersham-on-the-Hill was still known as Amersham Common while Amersham was what we now refer to as Old Amersham.

Not everyone who attested expected that they would have to go. Charles J Barker, 30, single, of Amersham Common, who ran his own motor haulage company, felt it was unfair that he should have to suffer the financial loss of going to war, when employees of other haulage contractors had been exempted (30 June). He had attested only “to show that I was willing.” He was advised to apply for compensation under the new Government scheme.

Not everyone who attested expected that they would have to go. Charles J Barker, 30, single, of Amersham Common, who ran his own motor haulage company, felt it was unfair that he should have to suffer the financial loss of going to war, when employees of other haulage contractors had been exempted (30 June). He had attested only “to show that I was willing.” He was advised to apply for compensation under the new Government scheme.

The impact of the war on local businesses, farms and estates was considerable. Some had government contracts which had to be fulfilled. HJ & A Wright of Great Missenden had orders for 24,000 ammunition boxes and 10,000 fuse cases (2 June 1916, p 2). A Reed, sawyer, Amersham Common, also contracted to the government, had already lost 6 men, and had to appeal for his gang sawyer Leonard Pudephatt, 27, single. In his submission he stated that the firm made most of its own machines and had patented several designs (26 May).

Very early on (31 March) TT Boughton, an agricultural and general engineer appealed for 9 of his employees, stating that he did work for 120 farmers and that his workforce, once 60 men, was down to 38. 7 were given exemption for 6 months, 2 for 3 months.

J Howard, a sawyer, wanted exemption for Jesse Redding, 26, the only one who knew how to operate a machine on which the employment of 7 other men depended. 6 months’ stay was granted (14 April).

Joseph Hatch farmed 320 acres, of which 50 were pasture. He had 30 milking cows, 10 working horses and 12 pigs. From 10 men, he was down to 4 men and a boy (31 March).

The Amersham area was predominantly agricultural. Many horses had been requisitioned on the outbreak of war, making cultivation and the transport and delivery of goods much more difficult. The Appeals Tribunal had to weigh the nation’s military needs against those of food production. Farmers complained that their labourers were leaving, even without conscription. Mr Gurney (2 June) cited higher wages in munitions factories as a factor, Mr Pudephatt’s men had said they would go unless their pay was increased. Even when he offered more money, one man left saying he had spent thirty years ploughing and wanted a change (26 May). Joseph Hatch was willing to pay a shepherd 30 shillings per week plus a shilling a head for every lamb reared and still could not find anyone (15 Sept), while Arthur Bates had offered boys 15 shillings a week plus threepence per hour overtime and £2 harvest bonus yet the money had been turned down (26 May).

Taking on lads was in any case a temporary solution in that they would be called up and by 1916 any hope that this would be a short war must have been extinguished. The alternative, as in so many areas, was female labour and employers appealing for their men were repeatedly enjoined to “try a lady” or “get a woman”. Many comments were made on the usefulness or otherwise of women.

AC Drake, of Cokes Farm, claimed that he “had tried women but could not make them useful” (18 Aug). Mr Denning, George Weller’s bailiff, was aggrieved that two women milkers had ruined two of his best cows worth £35 each. Getting women who could milk seems to have been difficult (14 July). George Newman of Ashley Green had applied to Lady Susan Trueman but was told she had no milkers available (3 Nov). A meeting had been held in February at the Amersham Conservative Club and addressed by Ernest Mathews, who offered the use of his dairy to women willing to learn, and canvassing of women by women was organised to try to boost the agricultural workforce. The reporter commented that very few of the farmers who had been invited turned up! The views of Mr Mathews and TT De Fraine were poles apart, which led to some interesting exchanges when Ernest Mathews appeared before the Tribunal. Some of the women he employed earned £1 two shillings a week, based on 15 shillings a week plus fourpence an hour overtime, and he had found that women could be useful after two or three days’ training. When Mr De Fraine was asked why he did not employ women [a solution, after all, that the Tribunal kept urging on farmers] his defence was that his farm at Chartridge was too close to Chesham’s factories where the women preferred to work.

AC Drake, of Cokes Farm, claimed that he “had tried women but could not make them useful” (18 Aug). Mr Denning, George Weller’s bailiff, was aggrieved that two women milkers had ruined two of his best cows worth £35 each. Getting women who could milk seems to have been difficult (14 July). George Newman of Ashley Green had applied to Lady Susan Trueman but was told she had no milkers available (3 Nov). A meeting had been held in February at the Amersham Conservative Club and addressed by Ernest Mathews, who offered the use of his dairy to women willing to learn, and canvassing of women by women was organised to try to boost the agricultural workforce. The reporter commented that very few of the farmers who had been invited turned up! The views of Mr Mathews and TT De Fraine were poles apart, which led to some interesting exchanges when Ernest Mathews appeared before the Tribunal. Some of the women he employed earned £1 two shillings a week, based on 15 shillings a week plus fourpence an hour overtime, and he had found that women could be useful after two or three days’ training. When Mr De Fraine was asked why he did not employ women [a solution, after all, that the Tribunal kept urging on farmers] his defence was that his farm at Chartridge was too close to Chesham’s factories where the women preferred to work.

It was recognised that women had their limitations. During an earlier clash of views on 2 June Mr Mathews had conceded that women could not plough or lift heavy weights and indeed there are frequent mentions of ploughing with a four-horse team, which would presumably be needed on heavy soils, being physically beyond both women and aged labourers (15 Dec), as well as needing skill and experience. Mr Mathews was then aged 69 and farming at Little Shardeloes as well as trying to keep his son-in-law’s business in London going. About half the 396 acres were arable and he had 397 animals (320 sheep, 60 cattle, 8 horses and 9 pigs). He employed 2 boys and 10 men, of whom 5 were above military age and 2 rejected by the military. He appealed for his shepherd who was also the only thatcher and rick-builder and his stockman who had veterinary skills. He envisaged having “practically all the milking done by women, with a man and a boy to help with the stock”.

Elsewhere it was recognised that women had other obligations. EH Forwood of Bendrose Grange, farmer, remarked that women “could not attend regularly, though did their best” (17 Nov). Everyone appearing before the Tribunal, however, was there to argue that they or their employees should not be sent into the army and was unlikely to display much enthusiasm for any potential replacements.

Women were already helping to run businesses. FWA Lane, 27, of Tyler’s Green, newsagent, cycle-agent and hairdresser, showed no understanding of the business’s finances and had to confess “the wife does all the money part” (15 Sept). It was felt that Frederick Saunders’s wife was capable of managing the Queen’s Head, Amersham Road, in his absence (26 May) while Mrs Frank Winkworth had managed and could manage their 37 acre farm and its milk round (30 June).

By the end of 1914 farming had lost 8% of its horsepower and over 12% of its permanent, skilled, workforce to the services, who had also enlisted much of the casual labour relied upon at harvest time. By early 1916 almost 25% of farm workers had gone from the land. The wet winter of 1914/15 which had hampered grain production had been followed in 1915/16 by one of the wettest and coldest winters on record. The army started to loan men back on a temporary basis to help on the land, though the men chosen often did not have the skills required. Finally, when the Labour Corps came into being early in 1917, the need for 30,000 men formed into Agricultural Companies was recognised.

Conscientious objectors do not seem to have been viewed with hostility. Edward Ernest Bibby, a trained member of the friends’ Ambulance Union (24 March), and Henry Frederick Coleman, 25, a boot-repairer of Whielden Street, who was willing to join the RAMC (7 April), were both granted exemption so long as they were engaged in the evacuation and care of the wounded. In contrast the tribunal was critical of men who applied for the RNVR or Air Services, viewing that as an attempt to dodge Army service (Oct 13).

Glimpses of lives later lost can be captured in these reports. Arthur Darvell, 32, married, appealed for a temporary exemption to sort and dispose of the stock he had acquired as an iron and metal dealer, mentioning that his three brothers were already serving and he was the last one left at home. He would go on to win the Military Medal, but he never returned to his wife and family (2 June).

The toll exacted from many families was severe. William Beeson, 32, married, a stockman working for Alfred Hoare of Town Farm, said he had four brothers on active service. One had been killed, one wounded and one was missing. The Tribunal, noting that William had been a Special Constable, commented that “the family had certainly done a good share” and gave him two months’ grace with no further appeal allowed (7 July).

Many unsuccessful appeals were made on the grounds of illness and incapacity of dependent family members. The tribunal’s attitude was that the loss of a wage would be made up for by the Army separation allowance and that other arrangements had to be made for care. Usually a couple of months might be granted to wind up a business or find a substitute to manage it. Joseph Hatch, asked how he expected to get his hay and harvest up, replied “I don’t know. It is a complete mystery” (16 June).

Twice the doings of the Amersham Tribunal were more widely reported in the press. The Aberdeen Journal of 10 October and The Sussex Agricultural Express of 13 October noted that after “animated discussion” the Tribunal had conclude that a recent circular from the Local Government Board made hearing agricultural appeals a “farce” and had exempted them en bloc, a decision not welcomed by the military representative. The cases went forward to the County Tribunal where Mr Standring explained in a letter that the circular had reached them just before proceedings began, they had had no time to read it properly and had acted on recollections of what they had read in the press about it and believed that all agricultural appeals were to be deferred until 1 January. This proved to be erroneous (3 Nov) and their knuckles were rapped by the County Tribunal who took over the appeals.

An Aberdeen paper, The Aberdeen Evening Express of 18 May, had already picked out “singular contrasts” in the cases being considered in Amersham, where one family had six brothers, five of whom were serving, while another had seven sons, not one of whom was serving. The one brother left was Harry Bowler, 24, a motor washer employed by Mr Mackay Edgar of Chalfont, who was granted three months exemption. The next case concerned the Peedle family of Prestwood, who were coal merchants, meal merchants and fruit growers with 14 acres of orchard. Three of the seven sons were abroad and Mrs Peedle, whose husband was a helpless cripple, pleaded that none of the four remaining could be spared from the business (12 May). Rupert Peedle, 23, was given one month’s reprieve, after which his case and that of his brother would again be up for review.

The reporting of such cases was perhaps designed to increase the pressure on men to join up. The Buckinghamshire Herald of 4 March 1916 reported that the determination of a number of ladies to attend the first meeting of the Amersham Appeals Tribunal led to an “animated discussion” about whether it was a wise provision of the [Military Service] Act that hearings should be held in public. In the end the meeting went ahead in public, but several times the ladies were asked to withdraw while some private and personal issues were discussed. The Herald reported cases, giving details but no names – “an under-gardener at Penn”. The Examiner, fortunately for us, gave full details of the applicants, thus allowing family and local historians the opportunity to winkle out a great deal of interesting detail which otherwise would have been lost when the decision to destroy the records of the Appeals Tribunals in every English county except Middlesex was taken.

NOTE: see Military-Service-Tribunal-survey-Dec-2015

This gives details of Appeals Tribunals and is to be kept updated.

1 www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/middlesex-military-service-appeal-tribunal. It is also the subject of a TNA podcast by Chris Barnes & David Langrish.

2 Geoff Bridger, The Great War Handbook, 2009, pp 60-61 and Gordon Corrigan, Mud, Blood and Poppycock, 2004, p 72-75. For detailed information on the groups see www.1914-1918.net/derbyscheme. For example all single males born in 1882 were in Group 16, married men born in 1877 in Group 44.

3 Originally applying to single men aged 19-41, the upper age-limit was swiftly extended to 45. From May 1916 married men were included. In 1918 the age limit was raised to 51 and conscription continued until 1920.

4 Robert Angel quoted by Jill Knight, The Civil Service Rifles in the Great War, Pen & Sword, 2004, p128

5 The Silver War Badge, for men honourably discharged, was also issued from around this time and perhaps both armband and badge were designed to prevent men from being harassed and presented with white feathers.

6 Date references are to the Buckinghamshire Examiner unless another publication is specified.

7 Presumably the cows got mastitis. Mr Denning was told he should have ensured that the learners were followed up by someone who would have properly stripped the cows’ udders. The Tribunal had a considerable discussion about women’s capabilities, which was reported on 3 November. Lt Sydenham, the military adviser, was very positive in his assessments, while TT De Fraine, the agricultural representative, said it was impossible for a woman to learn to milk in six weeks and that he would want a cheap cow for them to practise on. Lt Sydenham commented that women had been treated so cavalierly by farmers that they were now in short supply.

8 Buckinghamshire Herald, 26 Feb 1916

9 For details of the various initiatives see J Starling & I Lee, No Labour, No Battle, 2014, pp 63-76. There seems to have been little lasting impact on agricultural productivity in Buckinghamshire. Figures from the Agricultural Returns of 1913 and 1922 for the county can be compared in Kelly’s Directories of 1915 & 1924, p 5. There is a slight drop in the number of horses, but this could be due to the advance of mechanisation.