Pineapples and Slaves. How an Amersham family made a fortune from the growth of commerce in the Americas.

In 2013 the Amersham Museum had some interesting correspondence with Mairin MacMillan who was researching her Amersham family history. Mairin’s research had uncovered some fascinating facts which she shared with the Amersham Museum researchers. The information extended the Museum’s knowledge of the history of Beel House in Little Chalfont and its connection with Caribbean plantations. This article was written by Wendy Tibbitts in 2017. See also her article about Beel House.

This is a family story of adventure and politics; strategic marriages and tragedy; political connections and royalty; as well as a rollicking slice of Amersham history. The story begins when the New World, with its vast amounts of land and resources, was opening up trading and investment opportunities that brought wealth to those that were bold enough to exploit them. Young men with moneyed backgrounds who were willing to take the financial and physical risks in sending trading ships on the seven-week voyage across the Atlantic could make their fortunes.[1] One such man brought his family to live in Amersham.

Kender Mason was a City of London Merchant born in 1722 to William Mason a London Gentleman and property developer. For the young Kender Mason the seeds of enterprise were inherited from his father, and being brought up in Whitechapel near the busy London docks he saw at first hand the amount of money that could be made from sending trading ships to the West Indies. Kender Mason went on to build a business empire trading between the West Indies, North America, Africa and Britain.

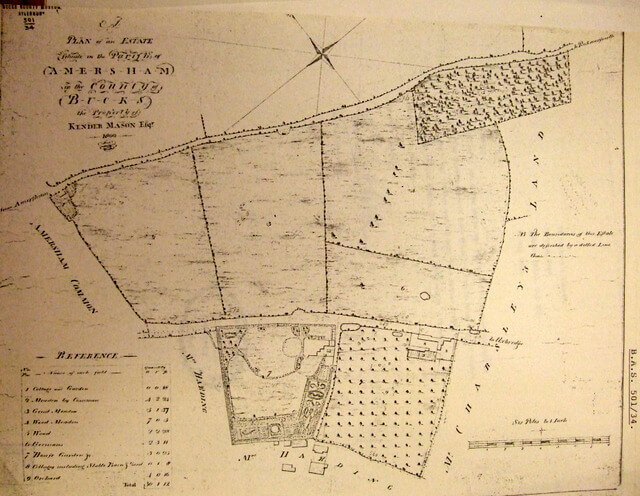

The Amersham connection started when, in 1762 at the age of 40, and having made a personal fortune, Kender Mason married Mary Pomeroy in All Hallows Church, Staining, in the City of London. Mary Pomeroy was the daughter of a wealthy linen merchant. Her grandfather, Sir William Pomeroy, was a director of The East India Company and an Alderman of the City of London. The Pomeroys, owned land around Gerrards Cross and the Chalfonts and after his marriage Kender Mason began buying up land and property in the Amersham Common area.

Building a business empire

Kender Mason’s fortune had been made, not always ethically or legally, by exploiting the opportunities that presented themselves at the time. The growth of the plantations on the British colonies in the West Indies started in the seventeenth century with small farmers growing tobacco and cotton. However these were slowly replaced by a more profitable crop – sugar. Sugar plantations required greater area and increased manpower.[2] As the need for more labour in the sugar fields increased the plantation owners resorted to using slaves kidnapped in Africa and brought to the Caribbean and North America by traders such as Kender Mason. These traders used a triangular trade route lasting about a year. They took commodities from the UK to Africa where the goods were exchanged for slaves and then the slaves were transported to the West Indies or the East Coast of North America. A Board of Trade document shows that in 1768 Kender Mason & Co trading out of Dominica’s free port of Roseau, sold 3710 Africans in Dominica and another 1713 in Puerto Rico. In 1772 the firm sold 5,003 Africans in Dominica. In exchange for the slaves the company received coffee, cotton and other commodities which were taken back to Europe to be traded for high prices.[3] The long and difficult journey was justified by the realised profits at the end of the voyage.

However there were many mishaps that could befall the vessel before it returned to England with its profitable cargo. Storms, disease, privateers, wars and politics were some of the hazards the ship owners had to contend with. One of Kender Mason’s ships, the Ann Snow, was seized by the French on 7 April 1745 and the crew taken prisoner. It was taken to a French port where the cargo was unloaded. The Royal Navy recaptured the ship and sold it as a prize ship. The loss of the ship and the cargo was an economic disaster for Kender Mason and in 1746 his creditors took him to the bankruptcy court where an award was made to them for the recovery of “sundry goods and merchandizes to a great value”. Mason was known to have “left his house and absented and gone into ports in the West Indies beyond the seas and not surrendered himself to the Commissioners to make a discovery of his estate and effects.” A reward of £10 for every £100 recovered was offered for anyone who knew of any estates or effects of the Bankrupt that could be recovered. Seven years later the bankruptcy was superseded (suspended). Obviously Kender Mason was eventually able to pay off his creditors, but how many suffered financial hardship during the long wait for their money? [4] These were not the only risks Mason took in his pursuit of profit. He was willing to take risks with his crew and vessels.

In February 1763, by the Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years War, Spain ceded Florida to Britain ushering in 20 years of British rule in Florida. Britain also kept many of the West Indian islands they had gained during the war and most of the former French territories of North America.[5] The British stationed 3000 militia at the Garrison of St. Augustine (the Spanish-built Fort Castillo de San Marcos) and at outposts in East Florida and these troops required feeding. Merchant Kender Mason, with his partner Arthur Jones, was contracted by the British government to supply provisions to the garrison and its outposts. This was not always an easy journey. Florida did not take part in the American War of Independence in 1775, but there were American ships and Privateers patrolling off the coast of Florida ready to capture British ships. This lucrative victualling contract lasted from 1764 to 1782 when the contracts were passed to their sons.[6] It is thought that the final payment to Mason was over £40,000.[7] This is equivalent to over £4million today and these supply ships ran concurrently with Mason’s ships bringing slaves from Africa.

Three months after the end of the Seven Years War, on 17 May 1763, the merchants and traders of the City of London, including Kender Mason, “waited on his Majesty [King George III]” and delivered an address to express gratitude for “the support and protection we enjoyed during the late war; …. and most sincerely congratulate your Majesty on the success of your truly paternal and humane endeavours to restore to your People, and to Europe in general, the blessings of peace.“ It was a long and sycophantic address to which the King gave an equally gracious answer. At the end of the audience the merchants had the “Honour to kiss his Majesty’s Hand.”[8] However for the plantation owners and traders, in the West Indies and North America, the British Parliament was about to bring more political upheaval.

The Seven Years’ War had severely damaged Britain’s finances and there was the ongoing expense of keeping 10,000 regular soldiers in North America. In order to recoup some of the expenses taxes were imposed on the colonists. In 1765 the Stamp Act was passed in Parliament requiring the citizens of the British Colonies to pay a tax on all paper documents. The tax only applied to the colonists. Understandably there was resistance and the cry of “No Taxation without Representation” began to be heard leading eventually to the Revolutionary War of 1775. The Stamp Act had a serious effect on the traders in Antigua because contracts, shipping documents, and invoices were an important part of their trading deals. Although at first Antigua and the other Leeward Islands in the West Indies objected to the Stamp Act and refused to accept documents with duty paid, it brought trade to a standstill and they eventually gave in to the traders’ protests and supported the Act. This then brought the island into conflict with the North Americans rebels who blockaded Antigua to the point where the islanders were threatened by famine.[9] During this time Kender Mason was reporting the effects of the blockade in letters to Charles Lowndes.

Charles Lowndes was Secretary to the Treasury in the Whig government of The Marquess of Rockingham. He lived at The Bury, Chesham, in a house built by his father William Lowndes who himself had once been Secretary to the Treasury. Both father and son became Members of Parliament in their later careers. The Lowndes family had distant cousins who were Planters in St Kitts and who went on to be prominent members of the legislature of South Carolina. Only after a change of Prime Minister and an embargo by the colonists on supplying any goods to Britain was the Stamp Act repealed a year later.[10] This correspondence between Mason in Antigua and Lowndes in London places Kender Mason in Antigua at the end of 1765. The letters are held in the National Archives with the papers of the Marquis of Rockingham who was Prime Minister at that time. It is therefore difficult to know if Kender Mason wrote to Charles Lowndes in his official capacity or whether they were acquainted socially through their South Bucks connections. It also raises the question of whether Kender Mason received the lucrative East Florida victualing contract due to this same social connection.

Between the American War of Independence (1776) and the signing of the Constitution (1787) Kender Mason and his cargoes were embroiled in a celebrated American legal case which in 1781 branded him “the enemy of America” by a court in Pennsylvania.[11] America was sensitive to any cargos from a British trader being brought into North America. At that time American law was still in its infancy and there was no clarity between the Federal Law and the Law of Nations.

Retirement to Amersham Common

Plantation owners and traders, once their businesses were established would leave them in the hands of managers or relatives and return to England to enjoy their wealth. Kender Mason Snr lived in Hatton Street, London. Although owning land in and around Amersham it is not clear whether it was he or his son of the same name that made Amersham his permanent home. Certainly By 1784 a Kender Mason was living in Amersham. He is on the voters list for Amersham having qualified as owning and occupying a property in the Parish. The previous year he had paid land tax for a house and land at Woodside. (Woodside was then an area of Amersham Common.) In 1787 Kender Mason bought more land in and around Little Chalfont which consisted of Cokes Farm, Abbotts Farm and part of Reeves farm “formerly called Woodside Farm” from Isaac Eeles and others. This became the Beel House estate.[12] The Mason family lived at Beel House for three generations. The house which was extensively modified in 1800, still exists on the White Lion Road between Dr Challoner’s School for Girls and GE Healthcare.

The Masons and Pomeroys jointly invested in many land and property deals in and around London. Their names appear in street names in Deptford and New Cross where there is a Pomeroy Street, Kender Street and several streets that start with Amersham. In Amersham Road SE1 is a pub called the Amersham Arms. In Monserrat there was a village called Amersham and an Amersham estate which was obliterated by the volcano eruption of 1995.

Kender Mason, Snr., and Mary Pomeroy had two sons. In 1763 Henry William Mason was born followed in 1765 by Kender Mason II, and when Kender Mason senior died in 1790 he divided his estate equally between them. His estate consisted of urban property in London and diverse plantations in Montserrat, Antigua, Dominica and elsewhere in the West Indies.[13]

By this time his eldest son, Henry William Mason, had changed his surname to Pomeroy in order to inherit his maternal grandfather’s extensive properties in London and the Home Counties. Henry Pomeroy had died leaving no male heirs and so under the terms of his will he left all his property to his eldest grandson, Henry William Mason, on the condition that he “assume the name and arms Pomeroy.” The transfer of the Pomeroy arms required a Royal Licence from the King George III. There is a memorial to Henry William Pomeroy in the North aisle of Chalfont St Giles parish church. He was living at Hill House, Bowstridge Lane, Chalfont St Giles at the time of his death in 1825.

Kender Mason II made Beel House his main residence and continued to increase the size of the estate. In 1798 he was paying land tax in Amersham on Stanley Wood and part of Flaxman’s Farm, and two other farms, as well as his own house and grounds. In 1812 he bought Willmotts Farm from John Grover.

Kender Mason II had six children with his wife Eliza Lovell who came from a wealthy family that had lands in Antigua and England. Her brother, Langford Lovell, lived at Mayortorne Manor , Wendover Dean. Eliza Lovell’s step-father, Baijer Otto Baijer, lived at 2 Bentinck Street, Manchester Square, London when he wasn’t on his plantation in Antigua. In 1791 at the age of 30 Baijer had inherited his father’s estate in Antigua which included “plantations, houses, buildings and negroes”. In the 1817 Slave Register he was listed as having 180 slaves. He and Kender Mason collaborated on several business ventures and the families were very close. In fact Kender Mason II died at his house in 1819, and both Baijer Otto Baijer and his wife died at Beel House in Amersham. Both are buried in St Mary’s churchyard in a tomb with railings on the east side of the church.

Kender Mason II was buried in the family vault in the Parish Church of Brentford. In his long and complicated will, written five years before his death, he stipulated that all his assets, other than those in Buckinghamshire, should be liquidated and invested in a Trust fund for the benefit of all his children. His wife was to get his carriage and pair and all his fixtures and fittings. His eldest son, Kender Mason III, was expected to be heir to the family estates in Buckinghamshire, but decided that the life of a country gentleman was not for him. Instead he became a Lieutenant in the Bengal Artillery and went to India. His father was so angry at his repudiation of his responsibilities as eldest son that he wrote a codicil to his will in which he revoked his bequests to his son of his books and articles of plate plus the Buckinghamshire properties and removed his ability to share in his siblings’ trust fund by telling his trustees to act “as if my said Son Kender Mason had never been born”. He did allow him to draw an allowance of £150 a year on the proviso that he did not contest his removal from the will. Two years after his father’s death Kender Mason III died in Calcutta aged 31 leaving no heirs.

Kender Mason II’s second son, Langford Lovell Mason, died at his grandfather’s London house aged 13. It seems that his grandson was already the owner of a plantation called Otto’s in Antigua.[14] He was also buried in the family vault in Brentford.

The third son, Henry William Mason, born in 1794 and joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12. As third son he was not expecting to inherit the family estates and sought a military career for himself. It seems very fitting that he chose a life at sea when is father and grandfather had made their fortune from shipping. After he was promoted to Lieutenant in 1815, he was occasionally stationed in Jamaica and South America.[15] In 1817, when the end of Napoleonic wars brought relative peace to Great Britain, the Royal Navy retired many of its officers on half-pay. Henry William Mason, returned to Amersham to assist his father in managing the family estate. Two years later his father died and against the expectations at his birth he inherited Beel House and the Buckinghamshire estate. He now had the wealth to afford to marry well and in 1822 he married Mary Heathcote, the niece of Sir William Heathcote, and they made their home at Beel House. She gave birth to a son, Henry William Mason in 1823, but he died 19 years later “after many years distressing illness” He is buried with his mother in St Mary’s, Amersham. Sadly his mother had died in 1825 giving birth to their second child, Mary Eliza. Inside St Mary’s church, on the West face, is a memorial to Mary Mason which reads:

removed from all the pains and cares of life

here rests the pleasing friend and faithful wife

ennobled by the virtues of the mind

constant in goodness and in death resigned

here in the solemn silence of the grave

to taste that tranquil peace she always gave

Henry William Mason married again in 1826 to Horatia Matcham, a niece of Lord Nelson. She gave him 6 daughters and a son. This son, George Nelson Pomeroy Mason, became a Commander in the Indian Navy. The Commander married twice and had two sons and two daughters. Both sons died as infants and so the Amersham branch of the Mason family died out with his death in 1890.

In 1829 Henry William Mason was made Sheriff for Buckinghamshire and later became a Magistrate and Deputy-Lieut. for Bucks. However, after the death of a baby daughter, Horatia Nelson Mason,(buried in the family vault at St Marys) in 1832, Henry William Mason, rented out Beel House and retired to Ramsgate and later moved to Devon. Four years later he sold Beel House, Cokes Farm and other lands to his brother-in-law, William Lowndes.

William Lowndes of The Bury, Chesham had married Kender Mason II’s daughter, Mary Harriett on 12 August 1830. This was the grandson of Charles Lowndes (Secretary to the Treasury) marrying the granddaughter of Kender Mason, Snr. They had two sons, William who inherited the family estate in Chesham and never married, and Joseph. Mary Harriett died in 1836 aged 32.

Kender Mason II’s other daughters, Eliza and Ann, married in a double ceremony in 1820. Eliza married Isaac Eeles the great nephew of Charles Eeles who built Elmodesham House in Amersham High Street. He was living in Fulham, but they later moved to Aldenham in Hertfordshire and then bought a small farm in Suffolk. They had two daughters. Eliza died in 1868. Anne Mason married William Merry, eldest son of William Merry, Deputy Secretary at War under Viscount Palmerston .

The Mason Legacy

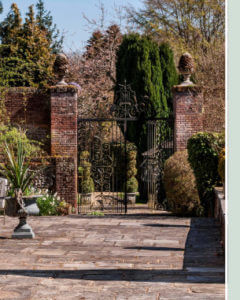

The connection between West Indies and the Masons influenced the street names used in the Amersham Common area. There is Pineapple Road and Pomeroy Close and on White Lion Road there is a public house which used to be called The Pineapple and has been renamed The Pomeroy. Pineapples were rare in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. The fruit rarely survived the journey back from the Caribbean unless travelling in fast ships and so were very expensive to buy. The ships did return with pineapple plants for the gardeners of the nobility to attempt to produce the fruit, but the plants required heat and humidity and were difficult to grow at a time before hot houses were heated by hot water circulation. The ultimate status symbol was to display a pineapple in the centre of the table at a grand dinner party. The pineapple therefore became a sign of wealth and hospitality and was featured in architecture, paintings, and household items. Beel House had pineapple-shaped finials on the roof, probably from the time of Beel House remodelling in 1800.

The plantation owners’ slaves were regarded as chattels and were often bequeathed in wills. Eliza and Kender Mason, whilst residing in Amersham were known to be selling their slaves in Antigua. An indenture made on 20th June 1800 “between Kender Mason of Amersham Common, Bucks and his wife Eliza, and Baijer Otto Baijer of Antigua at present residing in Bentinck Street, Manchester Square, London in consideration of £180 Kender Mason and Eliza his wife sell to Baijer Otto Baijer a slave named Hercules, a cooper, a female slave named Eliza, a house negro, and another female slave named Ann, also a house negro, which said three negroes were several years ago purchased by Kender Mason out of an African ship in Antigua, and for a considerable time have been in the possession of Baijer Otto Baijer upon his plantations in Antigua”. A further indenture was “made 20th March 1806 between Kender Mason of Beale House in the parish of Amersham, Bucks and his wife Eliza, and Francis Hales, shop keeper of the other part in consideration of £350 sterling Kender Mason and his wife Eliza sell to Francis Hales a mulatto slave woman named Sarah Dickman, and her five mulatto children named Eliza Hales, Abigail Hales, Jane Hales, Sara Hales and Frances Hales and their future issue forever.” This appears to be Francis Hales having to buy his common law wife and their children.[16] There is no direct evidence that slaves were used by the Masons in England. Slavery was illegal in Britain after 1772 but those slaves who had returned with their plantation owners were used as household servants and would have been given their freedom in return for continued service.[17] It is possible that the black servants of these Caribbean traders would have been quite a familiar sight to the people of Amersham. [18] So far there is no direct evidence of this intriguing possibility.

Conclusion

The Mason family were entrepreneurs. They were new money. They were not university educated like the Lovells and the Lowndes. They held no titles, but nevertheless they held power in the form of their wealth. They intermarried with county families and fellow plantation-owning families. The first generation of Amersham Masons seized the opportunities that the seventeenth-century New World offered and exploited them. The third generation fulfilled their duties as wealthy landowners by participating in the public life of Buckinghamshire. Telling the story of the Mason family history over three generations has revealed Amersham’s connections to historical events in the wider world.

Read about Amersham’s support for the anti-slavery movement by clicking on this link.

NOTES

[1] http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/passage.htm accessed 24/2/2017

[2] Port Cities, Bristol, http://discoveringbristol.org.uk/slavery/routes/places-involved/west-indies/plantation-system/ accessed 14/2/2017

[3] https://mvlindsey.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/8_american_slave_trade_american_free_trade.pdf

[4] London Gazette, 23 February, 1747 and 6 November 1753

[5] Wikipedia. Treaty of Paris (1763) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Paris_(1763) accessed 23/2/2017

[6] George Washington.Those Who Supplied His Army; http://www.ministers-best-friend.com/AMERIPEDIA-tm–George-Washington-Revolutionary-War-Suppliers.html

[7] Mairin MacMillan’s research.

[8] The London Gazette, 17 May 1763, Issue 10314, page 4. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/all-notices/notice?text=Kender+Mason&service=all-notices

[9] O’Shaughnessy, Andrew J. The Stamp Act Crisis in the British Caribbean, The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol 51, No.2 (Apr. 1994), pp 203-226 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2946860

[10] Stamp Act 1765, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stamp_Act_1765#Repeal accessed 22/2/2017

[11] Miller v. The Ship Resolution, , 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 19, 33 (1781). 247. 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 34 (1782) https://ssrn.com/abstract=907359

[12] : http://www.chalfonthistory.co.uk/nightingales.html

[13] George E. O’Malley Final Passages: the Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America 1619-1807 p. 311.

[14] Maurin MacMillan’s research.

[15] O’Byrne, William Richard, A Navel Biographical Dictionary, (London, 1849) https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=A_Naval_Biographical_Dictionary/Mason,_Henry_William&oldid=5417851. Accessed 10/2/17.

[16] From Mairin’s reading of Oliver, Vere Langford (ed.), Caribbeana being miscellaneous papers relating to the history, genealogy, topography, and antiquities of the British West Indies, (London, 1910)

[17] Sandhu, Sukhdev. The First Black Britons, (2011) http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/black_britons_01.shtml (accessed 20/2/2017)

[18] Mairin MacMillan’s research.