This page was written by Alison Bailey

Louise Jopling, who lived in Chesham Bois at the end of her life and is buried in Chesham Bois Cemetery, was an incredible woman who was incredibly famous during her life and deserves to be better known today. A very successful painter and writer she was born Louise Jane Goode in Moss Side, Manchester. The 90 years of her fascinating life was a period of unbelievable change for women. She was born in 1843 when women and girls were legally either the property of their husband or their father, and at the time of her death in 1933, British women had at last gained universal suffrage. The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act became law in 1928 and as a supporter of both Millicent Fawcett’s National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society and Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, this would have been hugely important to her.

Born one of 9 children, her parents, Frances and Thomas Smith Goode, a railway contractor, were both dead by the time she was 17. This same year, 1861, she met and married Francis Romer, a civil servant. They had two children in London before moving to Paris when Romer became secretary to Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild. The Baroness (a gifted artist herself) recognised Louise’s talent when Romer showed her some his wife’s pencil sketches. She suggested that Louise study art and after taking classes at the state technical school in Paris, Louise started at the studio of the anglo-french artist and engraver Charles Joshua Chaplin. Unusually he only accepted female students (the impressionist Mary Cassatt was also one of his pupils) and here Louise was able to study anatomy from nude models. This was impossible for a woman at that time in Victorian England. Returning to Paris at a later date, she also studied under the artist Alfred Stevens.

Even though her husband was sacked by the Baron because of his compulsive gambling, Louise Jopling remained on good terms with the family painting several Rothschild portraits. Her 1877 painting of Sir Nathan de Rothschild, in the uniform of the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry, can be seen today on the staircase at Hughenden Manor. Her 1877 portrait of Sir Nathan de Rothschild’s daughter Evelina is currently on loan to Waddesdon.

Now living in London she attended Leigh’s School of Art and found herself at the centre of London’s fashionable artistic circles, with support from other patrons such as the writer and journalist, (Charles) Shirley Brooks, who became the editor of Punch. She later contributed illustrations to Punch and was also the inspiration for some of George du Maurier’s cartoons satirising the fashions and manners of artistic society.

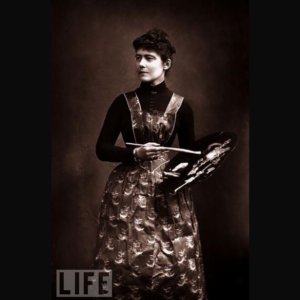

A versatile artist she mainly concentrated on portraits to earn money, often practising on self-portraits as she didn’t have to pay a model and money was scarce at the beginning. Her success as a painter was absolutely remarkable for the time and shows her courage and persistence. She faced constant rejection as a “lady” artist, having to battle to succeed in such a masculine world. Then, when she began to be successful, after exhibiting at the Paris Salon, Frank Romer deserted her and the children and threatened to seize her paintings and income when she requested a divorce. Louise had a new baby girl, Hilda and was still trying to recover from the death of her son, Geoffrey so this must have been a very hard time for her.

The Married Women’s Property Act of 1870 allowed for married women to keep their wages and investments independent of their husbands for the first time (full financial independence did not become law until 1882). The following year Louise successfully petitioned for a Judicial Separation. Romer’s repeated adultery, excessive drinking and violence towards his wife and children was evidenced in Louise’s statement and as Romer didn’t attend court to argue his case, custody of the children was granted to their mother, which was unusual at this time. More tragedy followed in 1873 with the death of their only daughter, Hilda before her 3rd birthday. Frank also died that year in New York leaving Louise free to marry again.

As a great beauty, and a self-confessed ‘flirt’, Louise would not have been short of admirers. Lucy Pacquette’s novel The Hammock imagines a romance between Louise and the French artist James Tissot, who she knew in London. However, her choice was the more conservative Joseph Middleton Jopling, who was 12 years older than Louise and had recently retired from the Civil Service. In her memoir Twenty Years of My Life she described her understandable concerns about marrying again, “I would be loading myself with extra duties, and all these duties would be as iron bars to my success”. However, she was convinced that “the best thing I can do for my reputation’s sake, and my boy’s is to marry again”. Louise’s remaining son, Percy, was 12 when his mother married Jopling in 1874.

Joseph Jopling was a watercolour painter of some renown. He had exhibited at the Royal Academy from an early age and had been an associate of the New Institute of Painters in Watercolours since 1859. He was a contributor to the Vanity Fair magazine and was employed officially to make drawings of the queen reviewing the troops. At the time of the Philadelphia International Exhibition in 1876, Jopling acted as director of the fine art section. An active member of the 3rd Middlesex Volunteers, He distinguished himself frequently in the National Rifle competitions at Wimbledon, winning the Queen’s Prize in 1861.

Jopling’s close friends included several leading artists of the time such as John Everett Millais and James MacNeill Whistler. Louise Jopling was now right at the heart of London’s artistic community. Success followed her marriage. She exhibited the oriental inspired subject painting Five O’Clock Tea at the Royal Academy in 1874 and sold it for £400. Five Sisters of York was shown at the Philadelphia International Exhibition in 1876 and It Might Have Been at the inaugural exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877. Sensational portraits of Louise by Whistler in 1877 (now in Glasgow University’s Hunterian Art Gallery) and by Millais in 1879 (now in the National Portrait Gallery) added to her fame. She was often mentioned in, and photographed for, the society pages, commended for her fashionable dress and social success “her studio parties are always interesting and she knows so many people who are always somebody in literature and art”.

The popular interest in the successful artists and writers at that time was similar to today’s fascination with reality TV stars and celebrities. Louise’s circle included other artists such as Kate Perugini, who was the daughter of Charles Dickens; Val Prinsep; Sir Frederick Leighton and Princess Louise, who was Queen Victoria’s daughter, and an accomplished sculptor. The actors Henry Irving, Ellen Terry and Lillie Langtrey were part of the same social circle as was the writer Oscar Wilde. At a party at the Joplings’ house in 1883 Oscar Wilde and James Whistler had the famous exchange after a witticism by Whistler, “How I wish I had said that” remarked Wilde. “You will, Oscar, you will” replied Whistler.

She was a frequent guest at Sir Anthony de Rothchild’s house at Aston Clinton, becoming close friends with his daughters Constance and Annie, whose portraits she painted in 1876 and 1878. House parties at Aston Clinton included politicians, artists, musicians, and royalty and led to many lucrative commissions. Constance encouraged her to rent a cottage locally, Stocks Cottage, Aldbury, as a weekend retreat and Louise’s love of the Buckinghamshire countryside dates from this period.

Another son, Lindsay Millais Jopling (named for his highly influential godfathers, Sir Coutts Lindsay, founder of the Grosvenor Gallery and John Everett Millais, the most popular artist of the time) was born in 1875. During her marriage to Joe Jopling, Louise was the higher earner and was so successful that by 1879 the family was able to move to a larger house in fashionable Chelsea where she commissioned renowned Gothic-revivalist architect William Burges to design separate garden studios for her and Jopling. She painted society portraits of the titled and wealthy and also of her friends such as the author Samuel Smiles (National Portrait Gallery) and the actress Ellen Terry. Her achievements are even more remarkable when you consider that as a woman, her work was unable to attract the huge fees that male artists were achieving at the time. In 1883 she lost a commission for 150 guineas which went to Millais who was paid 1,000 guineas for the same project.

Further tragedy struck Louise in 1881 when her eldest son, Percy, died of tuberculosis, followed by Jopling in 1884 at their home in Beaufort Street. After Joe Jopling’s death she let out his studio to the sculptor Maria Zambaco, Edward Burne-Jones’ model, student and mistress. The disastrous affair between Burne-Jones and Zambaco had caused a huge scandal 15 years earlier.

In 1887 Louise married solicitor, George William Rowe, a family friend who was 11 years younger than her. Rowe was a widower with a young son. The marriage brought financial security and a new home at Pembroke Gardens in Kensington. She established her art school for women in her studio here.

To escape from London for weekends and holidays, the Rowes rented various houses in Buckinghamshire, particularly in Chesham Bois. These included a cottage at The Woodlands and Greenacre in Copperkins Lane. In 1919 they moved permanently to Manor Farm, North Road where she used Arts & Crafts architects, Forbes and Tate to create a studio in the barn. Her stepson, George who was a commander in the British Navy, survived WWI but was killed two years later in a motorbike accident.

Throughout her long-life Louise Jopling encouraged and supported other women artists. She wrote books on painting to make it easier for women to teach themselves and founded her own art school for women in 1887. Frequently prepared to take on the art establishment she championed the right of female art students to work directly from live models without the customary ‘careful draping’. She joined the Society of Women Artists in 1880. Elected a member of the Society of Portrait Painters in 1891, she successfully lobbied them to allow the few women members voting rights. In 1902, she made history by being the first woman to be elected to the Royal Society of British Artists, RBA.

In addition to painting commercial paintings like Blue and White she was also prepared to be more controversial in her work contributing Weary Waiting to the 1877 Royal Academy Exhibition. In contrast to earlier works this doesn’t depict being a wife and mother as a particularly positive experience. In her memoirs she is honest about the difficulties of being the primary breadwinner. She often found the responsibility of continually searching for commissions and clients stressful. 1879 was a particularly difficult year when both she and Percy were seriously ill. However, she still produced 18 works.

Louise Jopling was a committed campaigner for Votes for Women, and a long-term supporter of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. She was a signatory on the 1884 “Letter from Ladies to Members of Parliament” and the 1889 Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage. In 1890 she held a drawing room meeting for the Women’s Franchise League. In 1898 she was a vice-president of the Central and Western Society for the Women’s Suffrage. In 1907 she subscribed to the WSPU. She hosted a drawing room meeting for the Women’s Freedom League in 1909. In 1910, she joined the New Constitutional Society for Women’s Suffrage which was against militancy but according to Elizabeth Crawford’s The Women’s Suffrage Movement “abstained from public criticism of other suffragists whose conscience leads them to adopt different methods.” She was a high-profile member of the Women’s Tax Resistance League, whose popular slogan was ‘No Taxation without Representation’. Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, another member of the Tax Resistance League, and equally famous, had a precious diamond ring seized by bailiffs for refusing to pay her servants’ taxes or her dog licence. When the ring was to be sold at auction, fellow activists attended to ensure no member of the public dared buy the ring. Instead the successful bidder was Louise Jopling, who promptly returned it to the Princess.

Another founder member of the Tax Resistance League was Marlow artist, Mary Sargant Florence. Together they were members of the Artists’ Suffrage League and the Suffrage Atelier, marching in processions and creating banners for the cause. The Suffrage Atelier was a crucial advocate of working-class female artists. They held evening classes in cartoons and illustration, lectures and life drawing classes in which suffragettes were often the models. Louise Jopling was one of the sympathetic, high-profile artists who hosted Atelier exhibitions of other women artists.

She also published poetry and she sent this rousing, comic verse to the suffragette paper Votes for Women in 1908:

Oh! Womenkind of England now

Be worthy of your blood;

Let courage shine upon your brow,

In spite of men and mud…

Come, Men of England! Show your pluck,

And free your women too;

About the House, there is no luck

Unless its ruled by two!

Louise Jopling wrote numerous letters on suffrage to the newspapers: “The qualities I most admire in a man? Ah! Many. But there is one I should like to see more highly developed, that is his sense of justice! Signed A VOTELESS TAXPAYING WOMAN.”

Another letter protests about the treatment of suffragette prisoners “surely the need for martyrdom ought to have disappeared with the dark ages. However future centuries will no doubt look back upon the 20th Century as quite one of the darkest in which the women of the land, in their demand for justice were treated as common criminals”.

After Louise ‘retired’ to Chesham Bois she spent more time on her writing. She had published numerous articles and stories and a book on painting “Hints for Amateurs” and two books of poetry. She now wrote her memoirs, Twenty Years of My Life which were first published in 1925.

She founded the Chiltern Club of Arts in 1919. This was an incredible legacy for our community as it became a major part of the educational and social life of our area. Many of the founding members, were artists and suffrage campaigners like Lucy Morley Davis (wife of geologist Arthur Morley Davis) and suffragette, Margaret Wright, but the Club attracted members from across the community. The president of the local anti-suffrage society, Lady Susan Truman was also a founder member. “The purpose of the club was to encourage an interest in art, archaeology, literature, music, crafts and outings” according to Patricia Smith, the last secretary, who donated several boxes of Club memorabilia to the museum. As her grandparents had first joined in the 1920s and her parents some years later, her collection of annual reports, minute books, obituaries, articles and photographs create an invaluable record of the 90-year history of the Club and its amazing women members.

She was president of the Bucks Art Society and in 1932 opened a permanent art gallery for the society in the Griffin Hotel. The 81 paintings on display included her own, Flora. What a shame such a gallery no longer exists in Amersham!

When she died at Manor Farm the obituary in the Bucks Examiner said that “When all has been said about her artistic activities, it is as a personality that Mrs Jopling-Rowe will be remembered. She retained her popularity to the last.”

Louise’s son Lindsay (known as Jop) after a successful career as an administrator in India, converted her Chesham Bois studio as a weekend house for his second wife, the distinguished singer, Joan Izott Elwes.

In 1935, two years after her death, the Chiltern Club of Arts held their annual exhibition in Amersham Town Hall. The exhibition included nearly 40 of Louise’s paintings (many lent by the family) and in place of honour, Millais’s portrait of her, which had been given as a christening present to his godson, Lindsay. ‘Ah, my godson! I never gave him a cup at his christening, so I’ll give him the “mug” of his mother now,’ he apparently joked. The portrait was a huge hit when it was exhibited and was normally on loan to, and exhibited at, the National Gallery (it is now owned by the National Portrait Gallery). However, according to the Bucks Examiner of May 3, 1935 “the gem of the collection was a self-portrait, loaned by the Manchester Art Gallery”. How incredible that these paintings were all on display in Amersham in 1935.

After Jop’s death in 1967, his son John Jopling, a barrister sold the barn and moved to Fingringhoe. However, Louise’s creativity has continued in her descendants with several musicians in the family. Her great-granddaughter Daisy is a successful violinist, based in New York with her own group, the Daisy Jopling Band.

This remarkable lady, who lived such a fascinating and incredible life, deserves to be remembered today. Dr Patricia de Montfort of the University of Glasgow is carrying out a research project into her life and has published a book. Louise Jopling: A Biographical and Cultural Study of the Modern Woman Artist in Victorian Britain, published by Routledge-Ashgate. More information can be found on her website www.louisejopling.arts.gla.ac.uk.

To see a selection of Louise’s paintings, click here.