DIPLOMATS, MADNESS AND “DISHONEST SERVANTS”:

A DARK TALE OF CHESHAM BOIS

Histories of Chesham Bois tend quickly to pass over Francis Peter Werry, if they mention him at all. This shadowy 19th century tenant of Bois House is described as a “retired diplomat” – but the truth is far darker and more complex.

Francis Peter Werry (1788-1859) lived at Bois House for around 25 years between 1825 and 1850. He served as a British diplomat during the tumultuous early years of the 19th century and in 1815 had witnessed first-hand the carve up of Europe after Napoleon at the historic Congress of Vienna, as secretary to the head of the British delegation, Viscount Castlereagh.

But Werry was sensitive, prone to illness and lived constantly in the long shadow cast by his high-achieving father of exactly the same name Francis Peter Werry (1745-1832), British Consul at Smyrna. His fragile mental health gave way completely: in 1823 he was forced to return to England from his post in Dresden, he suffered a breakdown and he was confined for two years in what his daughter described as a “barbarous” lunatic asylum.

When Werry then took over the tenancy of Bois House, his servants took advantage of his fragile mental state and stole from him. He moved from Chesham Bois to Herschels House at Upton-cum-Chalvey near Slough around 1850 and from 1854 spent his last five years “certified insane” at a private asylum for “well to do gentlemen” at Hillingdon.

The “who and what” of the servants’ crimes against Werry at Bois House are not documented in detail. But there are clues in the court records and census returns of the time and in his daughter Eliza’s account of his life.

“Dishonest Servants” at Bois House

In her introduction to her father’s memoirs published in 1861 (1) Eliza Werry (1823-1884) describes how Werry’s Danish-born wife Maria Ella brought her as a young child back from Germany to join Werry at a “lonely house in Buckinghamshire”. Her mother, she writes,

“…. bravely ventured in search of him – young, inexperienced in the way of the world, and totally ignorant of the English language – and found that he had shut himself up with his sorrows in a lonely house in Buckinghamshire.

“Here he was giving himself up to melancholy, while his servants were plunging him daily deeper in debt. Mrs. Werry’s task was a hard one; and she did all that could be done. She discharged the dishonest servants, reduced his establishment within the limits of his means, and paid his debts; but she could not “minister to a mind diseased”

The records of the County Assizes held at Aylesbury in March 1842 and Chesham Bois census returns shed light not just on these crimes but on the abject conditions endured by the poorest inhabitants of Amersham and Chesham at that time.

In March 1842, Amersham Common carpenter Thomas Matthews, 31, and his 33-year-old brother-in-law Charles Leverno (alias Charles Sabatini) of Chesham Bois were convicted of “larceny by a servant” and sentenced to two months in prison. At the same session James Halsey (33) of Chesham Bois was convicted of larceny and received the same sentence. The three men were all connected to Bois House and to each other.

James Halsey’s sister Sophia Caudell (born Sophia Allsey) was one of the Werrys’ servants of Bois House. Around 1850 she remained in their service when the Werrys took up the tenancy of Herschels House (later known as Observatory House), Upton cum Chalvey, Slough.

Charles Sabatini, born in Hyde Heath in 1810, married Alice Chilton in Chesham Bois Church in 1830. His family originated from Livorno in Italy and he was sometimes known as Charles Leverno. Charles’s sister Charlotte Sabatini married Thomas Matthews in Chesham Bois church in 1833.

In the 1841 census Charles Sabatini, a “paper maker”, is found living in a cottage in Amy Lane Chesham Bois with his wife Alice, their four young children, his sister Charlotte Matthews and her two young children: nine people in one small labourer’s cottage.

The reason Charlotte’s husband Thomas Andrews of Amersham is not with them becomes clear from the Aylesbury section of the 1841 census where we find “Thomas Matthews, carpenter” recorded as a prisoner at Aylesbury Gaol.

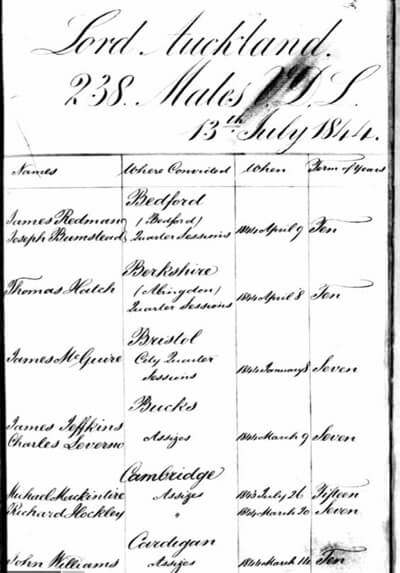

In 1844, just two years after Charles Sabatini’s conviction for “larceny by a servant,” he is back in front of the judge at the County Assizes facing the same charge. This time accused of stealing:

“at the parish of Sarratt, one metal (brass) tube, of the value of ten shillings, the property of Alfred Curtis. The Charge was proved.”

Alfred Curtis was the owner of Saratt Paper Mill.

That previous conviction clearly weighed heavily with the judge. Sabatini was sentenced to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for seven years. He set sail aboard the convict ship Lord Auckland on 13th July 1844 and arrived at Tasmania four months later.

Deprivation and Poverty

In 1851 Alice Sabatini,42, is living with her six children at 125 Town Field Yard Chesham as a dressmaker. Her husband Charles is away from home – still serving time in Australia.

In 1861 Charles’ father Thomas Leverno appears in a Parliamentary report into Paupers who are long term inmates of Union Workhouses. Thomas, it states, has been a “pauper” in Amersham Union Workhouse for 20 years. He died there later that year, aged 76.

The fate of the Sabatinis’ and Matthews helps bring to light the abject destitution faced by poor families in the district (2).

Son of the long-serving British Consul at Smyrna, Turkey

Francis Werry came from the other end of the social spectrum. He was born in 1788 into an ancient and distinguished family of seafarers and merchants who, by the end of the 18th century, were trading primarily in the eastern Mediterranean through the important Turkish port of Smyrna (modern day Izmir) as members of the Levant Company.

Britain’s diplomatic interests were then so closely intertwined with its trade that it was common for the most powerful merchants in a region to be appointed Britain’s Consuls and Vice Consuls, voted for by fellow merchants. And it was normal for these posts to be passed down within the most powerful families from father to son.

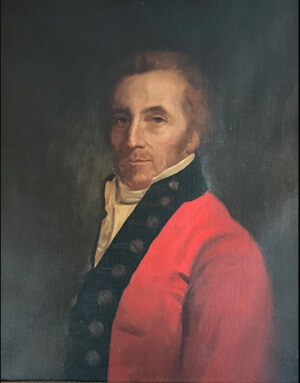

Werry was the third son of a powerful Smyrna merchant who (confusingly) had exactly the same name: Francis Peter Werry (1745-1832). Werry Senior, a leading member of the Levant Trading Company, was Britain’s Consul in the strategically vital port of Smyrna for 35 years from 1794 to 1829, until he retired aged 84.

His father was a hard act for young Francis Peter to follow: a brilliant and courageous soldier and naval commander, he became a highly influential merchant and diplomat. Nelson’s correspondence includes a number of confidential letters to and from Werry Senior sharing sensitive political and military intelligence about the region.

In 1793, just five and living in London, Werry Junior was separated from parents when his father left to take up his Smyrna Consul-ship. Young Werry was privately educated in a number of schools and did not see his parents again for ten years until 1803 when, now aged 15, they sent for him to live with them in Turkey.

The reunion must have been hard for Werry. In his memoirs he describes vividly how he struggled to recognise them.

In 1809, aged 21, he became a member of the Levant Trading Company and then left for London for a diplomatic career. He served in the Foreign Office and then as Charge d’Affaires at Vienna, St Petersburg, and Dresden.

Werry Junior was highly intelligent, imaginative, and articulate. He was desperate to persuade his father that his career was going well and promotion was imminent but his prospects were hampered by long periods of illness and the promotions never came.

His letters home over subsequent years show that the relationship between the sensitive son and high-achieving father became increasingly strained and eventually dysfunctional.

Things came to ahead around 1821 in Dresden when he injudiciously fell out with his superior the British Consul John Philip Morier. Relations between the two men became so bad that they were both recalled to London. For the struggling 33-year-old Werry (with his unshakeable 76-year-old father still going strong as the all-powerful Smyrna Consul) it was too much to bear. Back in England he had a breakdown and was committed to a lunatic asylum.

At some point after this, his relationship with his family broke down completely. His father inserted an apparently bizarre clause into his will of 1831 – that his son should go nowhere near his widowed-sister Eliza:

“The condition on which I leave to Francis Peter Werry the above bequests is that he shall not appear in Smirna (sic) during the existence of his sister the widow Darley. Should he break this condition the above legacies are null and void.”

This clause may have been influenced by his son’s unpredictable mental state: the Bodleian Library holds long incoherent letters he sent to his brother in Turkey which may have caused the family great unease.

Francis Werry at Bois House

It is not clear how Werry came to be living in Chesham Bois at Bois House around 1825, just as it is unclear who owned the house and surrounding land at that time.

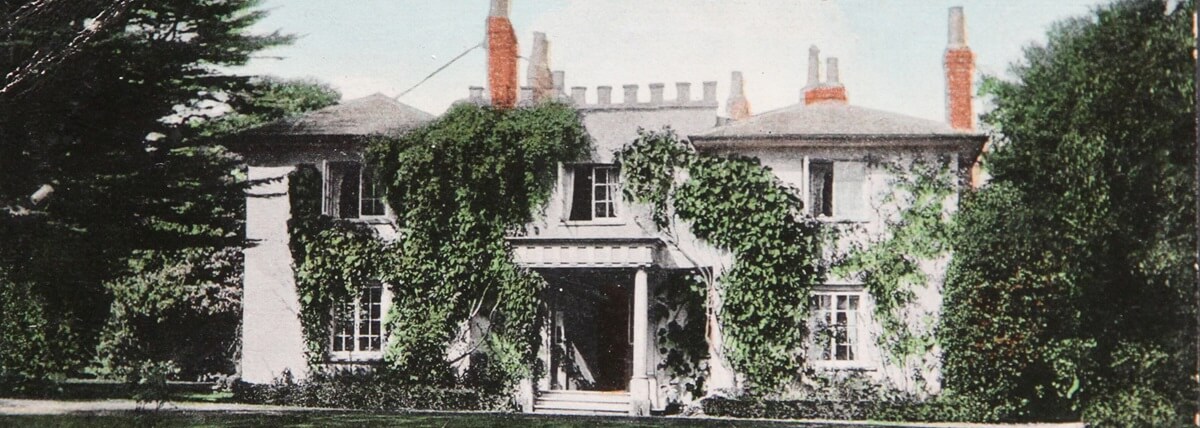

The original Tudor building had been extended considerably by the powerful Cheyne family after they took possession of the manor in the 15th century, to the point where it was recorded as “Bois Mansion”.

The house fell into decline after Charles Cheyne, 1st Viscount Newhaven (1625-1698) purchased much of Chelsea through his wife’s great wealth and moved his main home there away from Chesham Bois (Cheyne Walk etc).

The 4th Duke of Bedford bought the house and land 1738. When he died in 1771 without a surviving son his grandson Francis assumed the title. Many of his great estates – including Chesham Bois – were broken up and sold.

Sometime at either the end of the 18th or beginning of the 19th century the old mansion was partially demolished and the present fine country home built on the site. By the mid-1820’s Werry was living there as its tenant, it is possible to see evidence of that older building in the cellars of Bois House.

The title deeds for Bois House include a document from 1865 which sheds light on the ownership question. In a signed legal declaration Chesham landowner and farmer Benajamin Fuller of Little Germains, Fuller’s Hill affirms that he bought the house and surrounding land in 1834 through a lease and release agreement

“between Charles Salisbury Butler and Elizabeth his wife of the first part Edward Whitmore and Frederick Whitmore of the second part John Kirkman and John Nathan Bainbridge of the third part and me the said Benjamin Fuller of the fourth part”

In 1865 Fuller sold his Chesham Bois holdings to Charles Cavendish, 3rd Baron Chesham. By then the Werrys were gone, and the new tenants at Bois House were Edward Turst Carver and his family.

Around 1850 the troubled Werry had moved from Bois House with his wife Marie and daughter Eliza and was living as a tenant at Herschels House, Upton-cum-Chalvey near Slough. His mental state declined further and in 1854 he was admitted to the privately-run Moorcroft House Asylum For Lunatics at Hillingdon where he died in 1859, aged 79.

Werry’s grave – a poignant inscription

Photograph by Nick Gammage

His daughter Eliza was a gifted published writer. As well as editing her father’s letters and memoirs, she published in 1856 Memorials of Agmondesham and Chesham Leycester in Two Martyr Stories. And In 1885, a few months after her death, her novel Charcombe Wells appeared posthumously. It is said she may well have modelled the fictitious town of the title, a “grubby little town” nestled among beech woods to the north west of London, on Amersham.

When the Werrys left Bois House around 1850 the new tenants were Edward Turst Carver, his wife Elizabeth Tudor Key (whose family came from Blackwell Hall Farm) and their children. Two of Carver’s sons emigrated to Australia and his two daughters eventually bought Chesham Bois House from Lord Chesham.

Francis Peter Werry is buried with his wife and daughter in the churchyard of St Laurence’s, Upton cum Chalvey on the outskirts of Slough. The inscription on his grave, from Psalm 34, is a poignant reminder of his mental suffering:

“The Lord heard and delivered him out of all his distress.”

Notes:

- Personal memoirs and Letters of Francis Peter Werry edited by E.F. Werry (1861)

- I will be exploring the Sabatini family’s tragic decline from prosperous Hyde Heath landowners to prison and the Amersham workhouse in a separate article.