Aileen Mercy Kilburn by Alison Bailey with thanks to Fiona Murton, Aileen’s niece

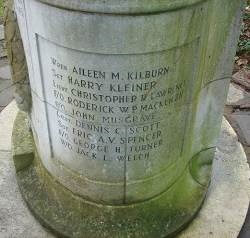

On Remembrance Sunday, November 11, 1949, Reverend Alvan Birkett led a service to re-commemorate the Chesham Bois War Memorial after the addition of the names of those service personnel from the parish who had sacrificed their lives during WWII. The service was well attended by the village with the usual representatives from the Parish Council, the services, local schools, scouts and guides, a marching band and of course the families of the young men and the one woman being honoured and remembered.

The relatives present that day would have included the previous incumbent of St Leonard’s, Reverend Henry Lawrence, whose son, Lieutenant Christopher Lawrence, died at El Alemein, Egypt 21 November, 1942. And Joseph and Esther Kleiner, of Dorset House, Long Park who were Jewish evacuees from London. Their son, Sergeant Harry Kleiner was the flight engineer on a Lancaster bomber, targeting the city of Dortmund when it was shot down over the North Sea 40 km west of the Dutch coastal town of Egmond aan Zee, 25 May 1943.

Also present that day were Charles and Elsie Kilburn of Trewithin, Stubbs Wood. They were there to honour their eldest daughter, Aileen, who was killed 18 March 1943 when she was just 19. Aileen’s sisters, Heather, 24, Sheila, 22, Christine 18 and Valerie, 15 would also have been there with their grandmother, Emily Robins. As well as mourning her granddaughter, Emily would have been remembering her son, Percy Robins, Aileen’s uncle. His name is also carved on the Chesham Bois War Memorial as he was killed in action 14 May 1917 near Arras in France when he was just 21.

In 1941 Aileen Mercy Kilburn answered the recruiting call “Join the Wrens – free a man for the fleet” and after training at Mill Hill was sent to HMS Midge, a Coastal Forces Base in Great Yarmouth. Standards in the Royal Navy were high, and Aileen would have been immensely proud to have been accepted as Wren 42634.

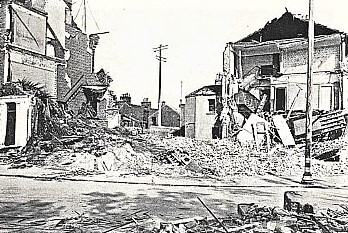

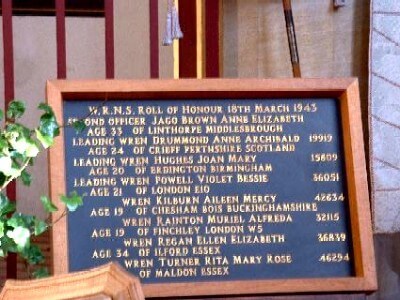

On 17th March 1943, there was an air raid. In bad weather at 6.28 am a lone Luftwaffe Dornier flew over Great Yarmouth and dropped six bombs. One scored a direct hit on a hostel where Wrens were sleeping. The house, at the corner of Queens Rd and Nelson Rd South, was destroyed and fire broke out. Rescuers tunneled into the rubble, using their bare hands until digging equipment arrived. Thirteen were rescued unhurt from the ruins, another 27 were severely injured and eight died, including their officer, 33-year-old Anne Elizabeth Jago-Brown and our Wren, Aileen Kilburn.

The Women’s Royal Naval Service (known as Wrens) was revived in 1939 at the beginning of WWII. By December of that year 3,000 women had joined and at the end of 1944 there were 74,620 personnel. As during WWI Wrens worked in clerical jobs such as telegraphists, signalers, weather forecasters and coders. Wrens plotted battle progress in operations rooms and worked as drivers and mechanics. However during WWII the list of ‘allowable activities’ was expanded and Wrens trained for many other jobs such as welders and carpenters, maintaining and repairing ships in naval bases. They were still not allowed on the ships on active service, but they did command and crew the powerful harbour launches, often going out in all weathers to collect people from landing craft that were anchored at sea. The boat crews also served as coastal mine-spotters, an important and dangerous job.

HMS Midge was a Coastal Forces Base located at Great Yarmouth. In 1943 there were 53 boats including mine layers, motor torpedo boats and motor gun boats used for escorting shipping convoys in the North Sea and for protecting the East Anglian coast. This was known as ‘E Boat Alley’ because the German fast attack boats, Schnellboots (called ‘E’ for enemy) were operating there.

According to a newsletter on the Coastal Forces website, “a posting to Coastal Forces was extremely popular and much sought after by new volunteers. While the work was challenging and exhausting, the feeling of being part of a team taking the fight to the enemy was, in their own words, extremely rewarding. The Wrens undertook splendid work, following crash technical training which enabled them to man a variety of technical posts. They became absolutely vital in the repair of the famously unreliable engines fitted in Coastal Forces craft in the early days of the war. They also had teams servicing guns, torpedoes, mines and depth charges, including the loading of these weapons onto the boats.”

Olive Swift (later Partridge) from Nottingham, also joined the Wrens in 1941, trained at Mill Hill and was stationed with Aileen in Great Yarmouth. She survived the attack on the hostel and after the war, wrote of her experiences at HMS Midge:

“I did my training at Mill Hill, near London. It was indeed a testing time. We did a lot of keep fit, and we were taught how to protect ourselves in an emergency, and what to do in a gas attack; which was a threat throughout the war, but to my knowledge, never actually happened. The marching was the hardest part, the feet suffered in the heavy laced up shoes.

We were allowed to choose our future job, and I cheerfully volunteered for maintenance, simply because I thought it would make a change from office work. In due course, five of us set off by train to Great Yarmouth. A more uninspiring sight can’t be imagined, in our ill-fitting uniforms and our safari type hats. Soon, I am glad to say, we were issued with the up to date hat, complete with band bearing the name of our base, HMS Midge.

We were to be billeted in a former large guest house, but found it had been bombed, so we were taken to a hotel near the sea front, lovely. Most of the civilians had been evacuated, but we had a large number of Service Personnel, Wrens, Waaf and the Royal Navy, ATS, not to mention frequent visits from American servicemen, stationed at nearby Norwich. We were issued with bell bottom trousers, a boiler suit, and oil skins, so we did wonder what we were getting into.

We soon found out. The five of us were marched down to the harbour, or base as we called it, where flotillas of motor gun boats, and motor torpedo boats where moored. MTBs and MGBs for short. There we were taken aboard, and down the hatch into the engine room. I don’t know which of us was more astonished, the engine crew or us. The general reaction was, possibly, ‘Oh my God’. The engines were hot, having just returned from sea, and the sailors were stripped to the waist. Daphne, a general’s daughter, who had led a sheltered life, took one look, and beat it back up the ladder. She went to Signals, a lovely girl, we became great friends, and cabin mates.

I never regretted my decision to stick with it. We were taught to change plugs, strip down gearboxes and distributor heads, and anything else needed to keep the Hall Scott, or Packard American engines, ready for action. We went out to sea on trials, when the job was finished, and stood on the deck, side by side with the men, as we sailed out of harbour. A mutual feeling of friendship and great respect grew up between sailors and Wrens, which lasted the whole four and a half years. We worked, danced, partied and laughed together. We also experienced great sorrow when any of the boats were missing or damaged. I remember one in particular, No. 313, which limped home with a great hole where the engine room had been. The entire engine room crew had been killed.

We were regularly shot at by low flying German planes as we marched down to the base to work. We ran for cover, they weren’t very good shots, nobody was hit. I must say though, the bombing was devastating; a lot of the service quarters were razed to the ground, including our own. I was sleeping in a top bunk, but found myself blasted from my bed, lying on the floor at the far end of the room, amongst a lot of rubble and glass. It was fortunate for me that I was not in my bed, as a large section of wall and a window fell on it.

There were seven of us in the cabin, and I can truthfully say that nobody panicked, we had great faith in our Naval friends, they dug us out alright, and if they hadn’t got a spade, they dug with their hands. Fire broke out, and being short of fire engines, we formed a chain, and passed buckets of water along, from a stand pipe. When the losses were made known, we found many of our friends were injured, or in shock, and had to be sent home. Worst of all, seven Wrens and our Officer was killed, but war time is no time for brooding and we survivors attended a memorial service for our dead comrades, and went back to work.

We had a very good social life, which helped us through the dark days. We went to the cinema a lot, the pictures we called it, and danced wherever we were invited. A favourite place was across the river, to Gorlston on Sea. It was called the Floral Hall, and a lot of fun was had there. Of course we took our turn on night duty, but whenever we were free, there was somewhere nice to go. If we had an off duty weekend, we would borrow a dinghy from an MGB and row or sail up to the Norfolk Broads. Other times we would ride our bikes into the country, and explore old churches. One Sunday we were in time for the service, and about six of us sat in a pew together. Unfortunately one of us got the giggles and set the others off. I think the vicar forgave us though, as he took us on a tour of the church and grounds afterwards.

In the evenings, we would often go to a fair on Britannia pier, with a glass of Babycham, and a cigarette in a long holder, we felt as girls do, war or peace, it was ultimate enjoyment.”

Family History

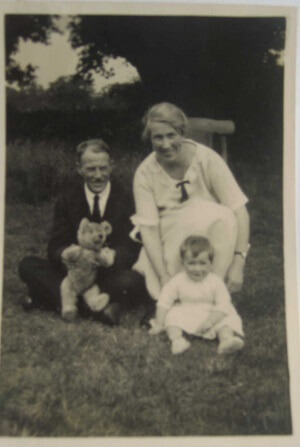

Aileen was the eldest of five sisters. She was born 13th June 1923 in Chesham Bois. Her father, Charles was 46 and her mother, Elsie (née Robins), was 28. Both originally from London, they had married at Amersham Free Church the previous year.

Charles Kilburn had been a career soldier. After the early death of his mother, Lucy, he joined the Prince of Wales Volunteers, The South Lancashire Regiment, as a musician. He was just 14. He served in India, and in France during WWI, reaching the rank of company quartermaster sergeant (CQMS), the non-commissioned officer in charge of supplies.

After leaving the army and marrying Elsie he worked as a builder’s bookkeeper and painter. The family lived at in Trewithin, a house built in the garden of Woodcot, Stubbs Wood which was Elsie’s parents’ house. Her father, Joseph Robins, was a solicitor’s managing clerk and had moved his family from Northwood to Chesham Bois in 1912.

Aileen was brought home to be buried in the Chesham Bois Burial Ground, and in 1952, the War Graves Commission added a Portland stone memorial with the moving inscription:

“There is not enough darkness in all the world to put out the light of one small candle”.

In addition to the Chesham Bois War Memorial, she is also commemorated on the WRNS Memorial at St Nicholas Church, Great Yarmouth and on a memorial wall plaque on the former site of HMS Midge.

Also see Alison’s article on Formidable Women

Sources

coastal-forces.org.uk/downloads/Newsletter_21.pdf

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/09/a3429209.shtml

http://www.rnhgy.org.uk/index.asp?pageid=385947

All photos of Aileen Kilburn and her family are courtesy of Fiona Murton, Aileen’s niece.