Gardener in Amersham

Charles Olney’s birth was registered in the last quarter of 1852 and he was baptised at St Mary’s Church Amersham on 7 January 1855, the son of William Olney, an agricultural labourer and his wife Ann née Norman. Both parents were born locally, William Henry in Amersham and Ann in nearby Chesham, and had married in Amersham on 30 June 1835.

In 1842 the family was living in Pineapple Yard, Amersham Common, according to the register of baptisms and in 1850 the same source records William Henry Olney as a beerseller. This is confirmed by the census which records the family at the Pineapple Beer Shop. At this point William is also working as a woodman and his two oldest sons are employed as boys in the same trade. A great deal of furniture was made in the Chilterns. Often lathes would be set up in the woods close to where the wood was coppiced and chair-parts sent on in bundles to be assembled in centres such as High Wycombe. Gradually it became more of an industrial process. Beer-selling was frequently combined with some other occupation such as stone-mason.

In 1861 William is a schoolboy aged 8. His three surviving older brothers are employed on local farms, the two oldest as agricultural labourers while Joseph, aged 10, is a shepherd’s boy. Amersham Common was an area of farmland stretching across the top of the hill which lies between the old market town of Amersham and Chesham. After the coming of the railway in 1892 the area was covered in houses and acquired the more aspirational name of Amersham on the Hill.

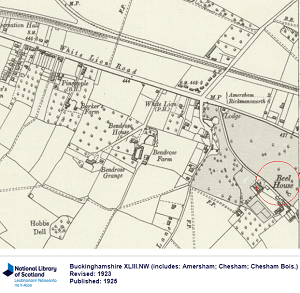

By 1871 Charles was a farm servant employed by Edward Weller at Woodside Farm, only a short walk from the family home. He appears to be following in the footsteps of his father and brothers. Ten years later he was married and working as a gardener for the new inhabitants of the local big house, Mr and Mrs Milner of Beel House. Dennis Milner was a retired barrister. Beel House has a number of finials shaped like pineapples and they also ornament gate-posts in the garden and probably gave rise to the naming of Pineapple Yard, where Charles had lived with his parents. A previous owner of Beel House, Kender Mason, carried on a great deal of trade with Africa and the West Indies and may well have imported pineapple plants as it was then fashionable to try and grow them and to produce them as the centrepiece at dinner parties.

Pineapples became a symbol of wealth and hospitality. Pineapple Road and the Pineapple public house (now the Pomeroy) attest to this part of the area’s history. According to Jennifer Davies, The Victorian Kitchen Garden, 1987 p 123, interest in cultivating pineapples in this country was at its peak in the 1860s and 1870s. It depended on the construction of fruiting houses, succession houses and sucker houses, all of which had to be kept at the appropriate temperature, so was not a cheap pastime.

By the time of the 1881 census Charles had moved from growing crops to growing flowers, fruit and vegetables and had also moved on in his personal life since he was now married with a daughter Grace, who can only be a few weeks old as the monthly nurse is still resident. As gardener Charles lived in one of the estate houses, Beel House Lodge. It looks as though he has moved hardly any distance from where he grew up. This may not be the full story, as his marriage to Elizabeth Hurlston, two years his senior, had taken place at Evenlode, Worcestershire on 12 May 1880. He may perhaps have got to know her while training as a gardener somewhere in that area during the nine years which had elapsed since the previous census.

Mrs Milner was widowed in 1888, but seems to have continued to be very active, hosting many fund-raising events at Beel House and raising money for charitable causes. She strongly supported the local National School and the local press reports many occasions when the schoolchildren were invited to Beel House for their annual treat. On other occasions the three Olney children were amongst those chosen to recite or sing songs. Local Directories show that the National School, Amersham Common, was built in 1873 for 100 children and enlarged in 1891 to accommodate 120. Maps show that it used to be located along Raans Road, a short distance from Flint Cottage, before moving to the site still occupied by St George’s School. In the evening of one of these festivities ‘the teachers and friends enjoyed the pleasures of a visit to the greenhouses, vineries and gardens of Beel House, all of which are beautifully kept under the skilful direction of Mr Charles Olney, the head gardener’ (Bucks Herald, 11 Aug 1894, p 7). This implies that the well-tended gardens had a significant part to play in the life-style adopted by the Milners and that Charles Olney’s skills were probably valued accordingly.

The 1891 census finds the family exactly where they were in 1881, but Grace is now 10 and has been followed by Ernest, 8, and Ida, 3. Charles’s brother-in-law, George Smith, 28, has also been taken on as a gardener at Beel House. After the death of her husband William Hurlston, Elizabeth’s mother had married Henry Smith and had two further children, of whom George was one.

The produce from the Beel House gardens was often exhibited at shows and charitable events. The social niceties are carefully observed in an extract from the Bucks Herald of 21 August 1886 ‘Mr D Milner of Beel House (gardener Mr. Chas. Olney) displayed some fine coleus, lilium auriatum, dracoena.’ Through such publicity gardeners’ prowess would have been well known locally. This would have been a great help had they desired to move to another employer and, as is the norm with such shows, no doubt they would all have been keen to discover just what their opposite numbers were putting on show.

Olney was even accorded a special showcase for an enormous gourd he had grown, which was put on display in the window of Barnes & Son, coach-builders, Church Street, Chesham. It weighed 79lbs and was 5ft 6½ inches in circumference (Bucks Herald, 16 October 1897). Clearly his status had risen considerably in the past few years. He was called upon to act as judge in 1907 at the St Mary’s School Festival (Buckinghamshire Examiner, 2 Aug 1907).

By 1901 the family has shrunk a little. Ernest is away from home, but not very far away. He is the most junior of four gardeners accommodated in the garden of Latimer House, Latimer, and no doubt gaining experience. Pamela Horn, My Ancestor was in Service, 2009 pp 52-58, shows that it was normal for aspiring gardeners to move on, gaining experience in each job in the various forms of cultivation which interested them. Ernest was typical in being the son of a gardener. The weekly Gardeners Chronicle which began publication in 1841 made available a huge amount of knowledge on horticultural matters and included helpful lists of what should be done each week as well as obituaries.

Grace is working as an Assistant School Teacher, so is benefiting from her education. Ida is only 13, an age by which at least one of her Olney uncles had already started work.

In February 1907 the death of Mrs Frances Milner brought about major changes and Beel House was put up for lease once more.

The body of Dennis Milner had been buried in the churchyard at Daresbury, Cheshire, amongst his ancestors, but his widow’s funeral took place at the church she normally attended in Latimer. The Buckinghamshire Examiner published an obituary with an account of the funeral on 22 February (p 3). One detail specially mentioned was the careful preparation of the grave which had been meticulously lined with daffodils, coronells [coronellas?] and moss by Charles Olney. He and his son Ernest were listed amongst the mourners. This was the last service which Charles could publicly perform for his employer. Producing a suitable display cannot have been easy in late February and it is not possible to know whether the choice of flowers had anything to do with the Victorians’ love of symbolism. According to Mrs L Burke’s The Illustrated Language of Flowers, 1856, coronellas meant ‘may success crown your wishes’. Appearing in early spring daffodils have always been associated with the renewal of life.

Under the terms of her Will, signed on 31 October 1905, Mrs Milner left £25 to Charles Olney. The Bank of England’s inflation tool shows that £25 in 1907 would have been just under £3,000 by 2018. It is difficult to gauge the spending power of such a sum, but between 1909 and 1913 Maud Pember Reeves and others studied the budgets of working-class families in steady employment in Lambeth whose income ‘round about a pound a week’ formed the title of the book she published in 1913. Servants who had been in Mrs Beel’s employ for two years or more each got a year’s wages in addition to their normal pay. It is possible that Charles would have been kept on for a while to prevent the gardens from deteriorating while the lease was up for sale.

The new occupants of Beel House arrived in 1909. Abram Arthur Lyle (1880-1931), was a director of the well-known sugar refining company founded by his grandfather Abram Lyle which later merged to become Tate & Lyle. The company prospered during the early years of the twentieth century and a large staff was employed at Beel House. Amongst them was Ernest William Olney, now 27, who had succeeded to his father’s place as Head Gardener. Curiously in 1911 he gave his birthplace in full as ‘Beel House Lodge, Amersham,’ but as a single man he was actually living in the Bothy in the stableyard with the two other resident under-gardeners. Possibly he felt his status as head gardener should have entitled him to live in the Lodge? Daniel Barker, Charles Olney’s predecessor, had been accommodated there with his family as the 1871 census shows, yet in 1911 it was home to a carter from a nearby farm and his wife.

The 1911 census finds Charles and Elizabeth Olney at 4 London Road, Moreton-in-the-Marsh, Gloucestershire with their daughter Ida, now 22 and a milliner. Charles puts his occupation as ‘jobbing gardener’. At 58 he was perhaps too old to find another long-term job with accommodation and this must represent a considerable loss of status and security.

It may have looked as though everything was otherwise set to continue in much the same way for another generation, but the First World War wrought drastic changes. Abram Arthur Lyle and his chauffeur Harry West joined the 1st battalion the Royal Fusiliers, which was part of the London Regiment. Lyle rose to be Lieutenant Colonel of the 30th Battalion. He returned to Beel House after the war but suffered from his injuries for the rest of his life. Harry West was killed. Ernest Olney also enlisted, initially in the Somerset Light Infantry. He disembarked in France on 27 July 1915. Later in the war he was transferred to the Royal West Kent Regiment as Private G/24630 and was killed in France on 23 February 1917. Click on this link for further details. His transfer to another regiment may have followed a spell of leave or recuperation as men were often drafted on their return to wherever the need was greatest. His name has not been found in casualty lists but he was definitely in London on 4 July 1916 because that was when he married Alice Maud Mitchell by licence at St Luke’s Church, Chelsea. She had applied for the licence on 11 June, giving her age as 29 and it had apparently risen to 30 on marriage. As leave was very hard to come by for a Private this may have been the only time they had together before Ernest was killed. His death was reported in The Times of 30 March 1917, p 5.

Alice Maud is a mysterious figure. On the marriage certificate her father’s name is given as John George Mitchell (dead), a clothier and tailor, but father and daughter did not appear together in any census, nor could a convincing baptism be located. Eventually the most promising candidate emerged as the daughter of Thomas George Mitchell (1847-1895), a tailor, and Mary Ann Bryan (1847-1901) who married at St James Westminster on 28 June 1868. Alice Maud’s birth was registered in the third quarter of 1882, Marylebone 1A 523, as Maude Alice and her mother’s name recorded, as for the birth of William Walter in 1878, as O’Brien. Elsewhere in the birth indexes it is variously Bryan or Obrien. The baby was baptized at St Andrew, Wells Street, in Marylebone with the parents’ names given as Thomas & Mary Ann and the child’s name expanded to Alice Maud Mary. This does record a plausible birth-date of 25 July 1882, but also demonstrates how this family consistently throws up inconsistencies.

Alice Maud would have been aged around 12 when her father died and she also lost her mother about six years later, so it is perhaps not surprising that fifteen years later details of her father’s name were muddled. The 1901 census shows her living with her mother and brother William Walter, now a silversmith. She was following in the footsteps of both parents by working as a tailoress.

When she applied for her husband’s medals on 26 October 1920, her address was the Alexandra Nursing Home, Stoke Devonport. The Midwives Roll shows that she qualified on 13 April 1921 in London and Register of Nurses gives the date of her registration as 17 October 1924, London. Both publications show her at a succession of addresses in Torquay from 1924 onwards and it was in Torquay that she died on 4 December 1962. Her age is given as 78 which, if accurate, would bring the possible year of birth forward to 1884. It is very frustrating not to be able to locate her in the 1939 Register so as to cross-check the alleged date of birth.

Charles Olney and his wife Elizabeth spent the remainder of their lives back in Amersham. The house in Lexham Gardens was named Wolford after Elizabeth’s birthplace, Great Wolford. As Amersham expanded, new buildings were put up here from about 1909 onwards and included a row of terraced houses designed by John Harold Kennard. They are both on the electoral register at that address until 1924 but the codes show only that Charles was resident and qualified through his occupation to vote while Elizabeth’s eligibility was gained through her husband’s. It does not show whether they owned or rented Wolford.

The war ended, having taken the life of their only son, but more deaths were to follow. The ‘flu pandemic which accounted for about 40% of the deaths of American soldiers was not halted by Armistice day and in 1919 brought two deaths within the family.

Their daughter Grace died on 4 March 1919 at the family home, Wolford, Lexham Gardens, Amersham, although usually resident at Annandale, Torwood Gardens, Torquay. The National Probate Calendar gives further useful details showing that she was the wife of Charles James Watt, an insurance official, although when registering his wife’s death Watt gave his occupation as ‘Transport Officer, Gold Coast.’ The details of this marriage have not been found anywhere. The Charles J Watt, insurance broker, found in the 1939 Register in a Wandsworth boarding-house looks a possible candidate for Grace Olney’s husband. His birth-date is given as 16 April 1883 and he is married. The 1901 census has a Charles James Watt aged 17 living with his father Thomas Watt, a journalist, at 20 Fairlawn Grove, Acton, and working as a copyist in the Civil Service. He was born in Guyana, so maybe the various foreign connections would help to explain the absence of any apparent record of the marriage as well as of his birth.

Elizabeth Olney, having suffered the death of the second of her three children, succumbed to the same infection less than a week later, on 12 March. Dr Hardwicke diagnosed influenza in both cases but while Grace had developed pneumonia her mother’s illness had caused oedema of the lungs. Both were frequent complications

Ida has left a more discernible trail. In 1914 she married Albert Bolton, a carpenter born in Amersham on 25 October 1886, the son of Thomas Bolton and Ruth née Bedford. His brother Harry became a nurseryman, so there may have been some link formed with the Olney family through shared gardening interests. Harry and two of his brothers gave their lives in the First World War.

For further details see https://amershammuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/10v2.pdf and https://amershammuseum.org/history/research/wwi/soldiers/

Albert joined the Royal Naval Air Service, where his skills as a carpenter would have been useful for working on aircraft built of wood and canvas, on 28 September 1916, about a month before his 30th birthday. Training as an Air Mechanic he moved on from Crystal Palace to Wormwood Scrubs, Cranwell and Eastchurch and lastly to HMS Daedalus, an RNAS station at Lee-on-Solent. When this base was taken over by the newly-formed Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918 Albert became no 221270 in the new service (See ADM 188/602, F21270, and AIR 79/1994). Ida and her small daughter presumably lived with her parents while he was away as the RAF recorded Wolford, Lexham Gardens, as her address. The year after Albert’s return, following his discharge to the Reserve on 5 March 1919, the couple had a son. Albert’s brother Arthur also survived, having served with the 1st/5th Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment (service number 36496) and in the Military Foot Police as no P18801.

In 1924 Charles Olney’s life came to its end. He had survived his wife by five years, but their age on death was the same, 71. Ida was then left as the sole survivor of this family of five.

This research was done by Gwyneth Wilkie as part of the Family & Community Historical Research Society’s 2019 mini-project on gardeners and is published with the kind permission of FACHRS.