in the English language’

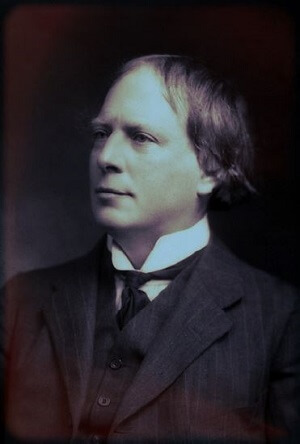

(c1908)

Arthur Machen:

Ecstasy and Sin in Amersham

By Steven Prizeman

A face glimpsed at a window fills the observer with terror; an unearthly femme fatale triggers a slew of suicides among society men; a dissolute youth takes medicine that has stewed too long on a chemist’s shelves and dissolves into seething black goo! These are just some of the plot elements that made Arthur Machen briefly notorious as an author of the 1890s’ ‘Decadent’ movement in literature – but that was all long before he came to live in Amersham in 1929. In the intervening years Machen was an actor, a journalist, a dabbler in the occult, a cult figure himself, and the inadvertent creator of a bona fide legend. But, unlike some of his ornately structured stories, let’s begin at the beginning.

Machen (pronounced to rhyme with ‘bracken’ rather than ‘taken’) was born Arthur Llewelyn Jones in 1863, in the small town of Caerleon-on-Usk, South Wales, the son of an Anglican clergyman. ‘Machen’, his mother’s maiden name, was added to the surname to satisfy a condition for receiving a bequest from one of her relatives. The family may not have been wealthy but from an early age Machen found riches in the beauty, history and myths of his birthplace, later writing: “I shall always esteem it as the greatest piece of fortune that has fallen to me, that I was born in that noble, fallen Caerleon-on-Usk, in the heart of Gwent.” Why? Because that “little silent, deserted village” of Caerleon “was once the golden Isca of the Roman legions [and] is golden for ever and immortal in the romances of King Arthur and the Graal and the Round Table”.

In 75AD, and for centuries thereafter, Caerleon (known as Isca Silurum or Isca Augusta) was home to the Second Augustan Legion, stamping a Roman presence on the town that is still visible: Roman walls, baths, the foundations of a legionary barracks (the only one to be seen in Europe), and the largest amphitheatre in Britain. In the long years separating the Romans from Machen these ruins had given rise to legends – that Caerleon was the Camelot of King Arthur and the grassed-over mound of the amphitheatre his Round Table. Naturally, with Arthur came an association with the Holy Grail (or Graal) – a lifelong obsession for Machen, who became an expert in its lore. Machen was not alone in his Arthurian interest: in 1856 Alfred, Lord Tennyson had worked on his epic Idylls of the King while staying at Caerleon’s ancient coaching inn, the Hanbury Arms. Today, in the National Roman Legion Museum, in the centre of the town, can be found a host of jewels, tombstones and other artefacts discovered locally which fired the young Machen’s imagination and fed into his tales.

To this heady mix of history, legendry and landscape were added the High Anglican religiosity of Machen’s upbringing and education at Hereford Cathedral School – and his adventurous reading habits. By his early teens he had read The Arabian Nights and Thomas De Quincy’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater. The state of mind produced by all these influences was revealed much later in Machen’s semi-autobiographical novel The Hill of Dreams (1907), in which the emotionally overwrought protagonist, an aspiring writer, leaves his small Welsh home town to pursue success in London. He fails miserably – losing himself in drug-induced dreams of life in a Roman city.

Machen’s path was (by comparison) more successful, more cheerful and apparently unclouded by any drugs other than ale, wine, an occasional absinthe, and copious amounts of pipe tobacco – but The Hill of Dreams does seem to depict a possible fate he contemplated for himself. In the event, Machen’s real life had a full measure of poverty, loneliness and, indeed, misery before he reached its sunnier uplands. But, most of all, Machen had London, to which he first moved in 1882, at the age of 19. London and Caerleon would remain the two poles of Machen’s life, both geographically and imaginatively.

Despite a few false starts in finding employment, Machen wrote while eking out a living as a private tutor. He “lived on dry bread, green tea and tobacco, and saved money […] I inhabited one room of a house in Clarendon Road, Bayswater. It measured, I should say, ten feet by six. There was no fireplace in it, so in Winter I sat in my greatcoat and made the best of the gas-jet. I was almost without a friend in London, so life on the whole was rather lonely.” But in 1884 his whimsical monograph The Anatomy of Tobacco was published by George Redway. The book did little if anything to improve Machen’s finances.

Over the next couple of years, things got worse before they got better. Machen’s father went bankrupt in 1883, his mother died in 1885, his father in 1887. Redway helped Machen with work: he commissioned the zealous Anglo-Catholic to examine his large stock of esoteric second-hand books “and a rather elaborate catalogue was issued, called The Literature of Occultism and Archaeology”. Then he commissioned Machen to translate (from sixteenth-century French) the Heptameron, a large collection of stories by Queen Marguerite of Navarre. This was much to Machen’s taste, who also wrote and self-published his own medieval entertainment, The Chronicle of Clemendy (1888).

By the early 1890s Machen – having inherited some money from his relations – was living in far more salubrious surroundings in Bloomsbury. Nor was he lonely, being married to Amelia ‘Amy’ Hogg, a progressive young woman who moved in literary circles and introduced Machen to Jerome K Jerome (of Three Men in a Boat fame), who became a good friend. Machen was also acquainted with the chief celebrity of the day, Oscar Wilde; Wilde praised Machen’s short story A Double Return (about mistaken identity and an inadvertent adultery) for having “fluttered the dovecotes”. Machen’s most enduring friendship was also thanks to Amy, who introduced him to Arthur Edward Waite – an American-born expert (and voluminous writer) on a host of occult topics, including the Grail. They remained friends until Waite’s death in 1942. But, late in 1894, it was time for Machen’s literary breakthrough.

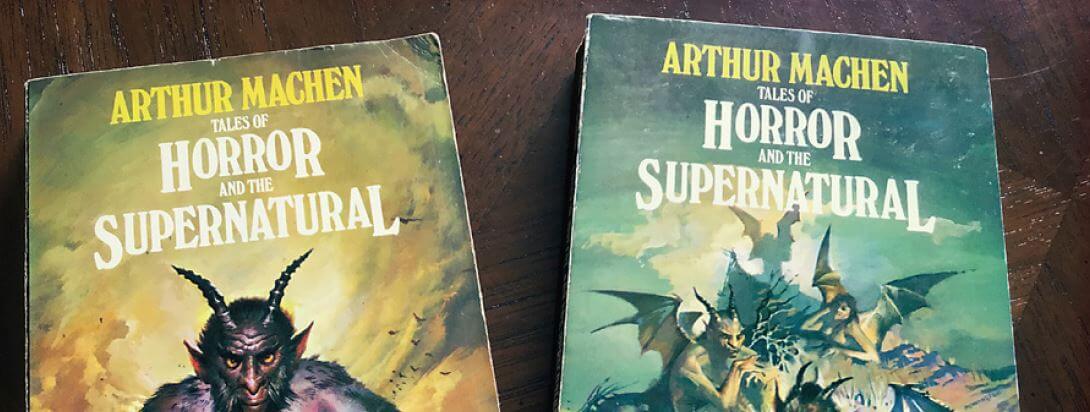

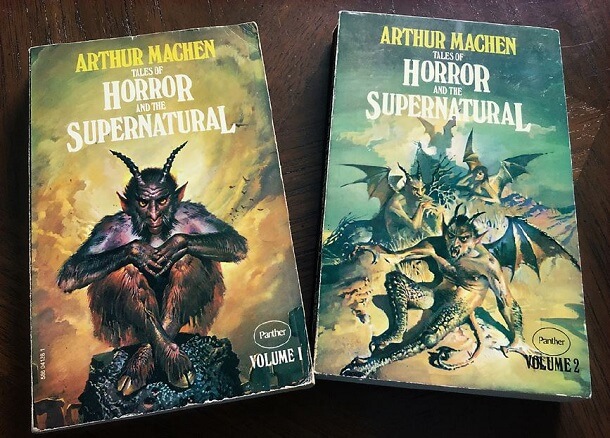

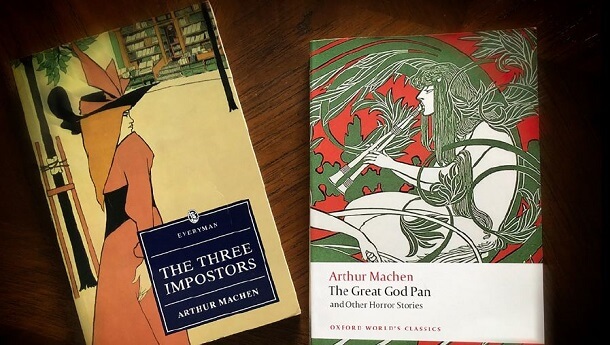

The Great God Pan and The Inmost Light, a slim compilation of a novella and a short story, made a deep impression on all who read it. Often, not a good one. Stephen King, the present-day master of horror fiction, has hailed The Great God Pan as “one of the greatest horror stories ever written. Maybe the best in the English language”. Starting with a bizarre experiment in brain surgery in the Welsh countryside, it leads to the string of suicides mentioned previously, before culminating in the awful explanation of the connection between the two. Most reviews were negative (Machen made a practice of collecting bad ones), with the critics largely divided between those who were unmoved and those who found the story so appalling it should never have been written. On one hand, the Chronicle said: “His horror, we regret to say, leaves us quite cold… and our flesh obstinately refuses to creep.” On the other, the Westminster Gazette described it as “an incoherent nightmare of sex and the supposed horrible mysteries behind it, such as might conceivably possess a man who was given to a morbid brooding over these matters, but which would soon lead to insanity if unrestrained”. (Readers who peruse The Hill of Dreams will find the charge of ‘morbid brooding’ sufficiently proven.)

Machen followed Pan the next year with a work in the same vein: The Three Imposters, a carefully crafted novel featuring a selection of stories – a literary forerunner of the portmanteau horror films of the 1960s and ’70s. The plot that frames and connects these tales is that of a ‘Young Man in Spectacles’ hunted relentlessly across London by a trio of outrageously lying assassins, all of whom cross paths with Dyson, a dilettante investigator of occult matters who is a recurring character in Machen’s early fiction. Jerome K Jerome said of Machen: “For ability to create an atmosphere of nameless terror I can think of no author living or dead who comes near to him.” Jerome loaned his copy of The Three Imposters to Arthur Conan Doyle as a nighttime read. Doyle, returning the book, observed: “Your pal Machen is a genius right enough, but I don’t take him to bed with me again.”

But timing – in literature as in so many things – matters a lot. In 1895 the scandal that broke around Oscar Wilde’s sensational trial and conviction for homosexuality (then illegal), turned reading public and publishers away from all things associated with the ‘Decadent’ movement. Machen always denied ever having been part of that, but, with both Pan and The Three Imposters being issued by John Lane (publisher of the infamous Yellow Book literary journal, central to the ‘Decadent’ movement), page decorations by Aubrey Beardsley, and the very style and incidents of his writing to testify against him, a breakthrough to a mass readership once again eluded him. (It is, however, worth noting that while Machen was hovering at the fringes of notoriety, The Casanova Society published the first complete English translation of The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova, the louche Italian adventurer, translated by Machen several years previously. With twelve volumes, running to approximately 4,500 pages, it was a monumental achievement and remained the definitive version for years.)

This professional slump was soon followed by personal tragedy: in 1899 Amy Machen died of cancer. “My own life was dashed into fragments,” said Machen, “I ceased to write.” The loss seems to have pushed the author into a long-lasting nervous breakdown and to the brink of suicide, averted at the last moment by a religious vision in which his room seem to move and dissolve around him. Life had already taken on the quality of an exotic Arabian Nights adventure, in which he smelled strange incense in the streets of London and felt like he was walking on air, rather than the pavement. He also began to meet people who seemed like avatars of characters from his own stories: the Irish poet WB Yeats was, surely, the Young Man with Spectacles. Throughout 1900 Machen felt himself to be continually approached by strangers who would regale him with fantastic tales of their adventures or secret purposes. It was an atmosphere perhaps not helped by his joining, in search of answers, the most prestigious occult society of the day, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (into which he was introduced by Waite). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, and Edith Nesbit, author of The Railway Children are sometimes said to have been members; the infamous occultist and writer Aleister Crowley certainly was. Machen found his experience of the Golden Dawn unhelpful but, by the end of the year, reality seemed to have been restored. He moved forward in life in exactly the way one would expect: by becoming a professional actor.

As a member of the Benson Company, Machen performed a host of (mostly small) roles in venues in London and up and down the country, while continuing to write. In 1903 he married one of the Benson actresses, Dorothie Purefoy Hudleston, with whom he would later have two children: son Hilary and daughter Janet. Machen thoroughly enjoyed treading the boards but acting was no more remunerative than his other occupations. In 1910 he entered a career to which he had aspired since youth: Fleet Street journalist.

For the London Evening News Machen covered all manner of stories, large and small, travelling widely to report on trials, processions, sporting events, Tube extensions and to interview celebrities and ‘the man in the street’. He found the work mundane, for the most part, but it had its moments, such as reporting from the scene of the Sidney Street Siege – a full-scale gun battle in Stepney, in 1911, between the police and army on one side and a gang of murderous Latvian anarchists on the other.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Machen also began contributing patriotic morale-boosting stories. One of these The Bowmen (1915), set during the perilous early days of the war, was to take on a life of its own. In August 1914, the hard-pressed British Expeditionary Force in Belgium retreated to Mons, pursued by a larger German army that threatened to catch and engulf them. At Mons the BEF rallied and, though outnumbered and outgunned, halted the Germans, inflicting heavy casualties. In Machen’s fictional account (presented as a report from one who was there), the victory was attributed to a soldier’s earnest prayer to St George being rewarded by the timely intervention of the ghosts of the Tommies’ forebears – the bowmen who fought at Agincourt. Within weeks of its appearance, countless tales of ‘The Angels of Mons’ were being repeated across the press – and were vigorously defended by self-appointed authorities when Machen tried to set matters straight. He had unwittingly created a legend in which people wanted wholeheartedly to believe, and he got no thanks for drawing attention to its fictional origins. The end of the war was, of course, a great relief for everyone – but it also marked a particular upswing in Machen’s fortunes.

In 1918 the American writer and critic Vincent Starrett published an essay, Arthur Machen: A Novelist of Ecstasy and Sin, hailing the author as a shamefully neglected genius. “With singular unanimity critics for thirty years have slighted the work of Arthur Machen,” he lamented. For Starrett: “Machen is the outstanding artist of his time, and one of the great masters of all time.” His astute title took as its clue one of Machen’s best stories, The White People (1899): written mostly as a naïve stream of consciousness in a girl’s diary, it reveals how she is gradually inculcated into the practice of witchcraft. For Machen, ‘ecstasy’ means “beauty, wonder, awe, mystery, sense of the unknown, desire for the unknown rapture, adoration, a withdrawal from common life… He writes of a strange borderland, lying somewhere between Dreams and Death, peopled with shades, beings, spirits, ghosts, men, women, souls – what shall we call them? – the very notion of whom stops vaguely just short of thought. For him Pan is not dead; his votaries still whirl through woodland windings to the mad pipe […] and carouse fiercely in enchanted forest grottoes (hidden somewhere, perhaps, in the fourth dimension!).” Starrett also admitted that “the sense of the futility almost of attempting to explain Machen becomes more pronounced as I progress. You will have to read him.” He ends with an accusation: “posterity is going to demand of us why, when the opportunity was ours, we did not open our hearts to Arthur Machen and name him among the very great.”

And, over the following decade, hearts did open to Arthur Machen. A ‘boom’ followed as his writing was reprinted in both popular and collectable editions on both sides of the Atlantic, cheering the author and giving him and his young family a good and reliable income. In these years he came to the attention of the American author of ‘weird fiction’ HP Lovecraft (another author neglected in his lifetime), who numbered Machen amongst the very few ‘Modern Masters’ of the genre in his (eventually) highly influential monograph Supernatural Fiction in Literature (1927), and named him directly in several of his greatest stories, including The Call of Cthulhu and The Dunwich Horror.

But nothing lasts forever. By the end of the 1920s the boom was over and Machen’s finances were straitened once again. Where does an ageing couple with little money retire? Amersham – a town with which Machen had been familiar for years as the home of his friend and frequent correspondent Paul England, and was close to his beloved London. And so, on Monday 24th June 1929, Arthur, aged 66, and Purefoy (‘Dorothie’ was never used) moved into ‘Lynwood’, 48 High Street, Old Amersham.

In September 1933 Machen extended an invitation to a correspondent (Dr John Ireland) to attend an event all Amersham residents know well:

Next Tuesday is Amersham Fair; an ancient, noisy, and gaudy business, stretching the whole length of this old street – which has altered little in the last hundred years. Will you come down and look at it, and listen to it? If so, we should be very glad to see you between 6 & 7. There will be a sandwich and a glass of punch. If you come, remember that this house is in the Old Town at the bottom of the hill. Over the door, is the inscription, LYNWOOD, and it is best to knock, not ring.

Plus ça change! But Amersham had its perils (noted in a letter to another friend, Colin Summerford):

… just before Christmas I fell down stairs and gave myself a very nasty shock, and a few days later had a severe and lasting fit of gout. Like the clergyman in Hamlet I lay howling. Now, I am glad to say, we are all as well as we are likely to be.

Machen often invited his friends to come down to Amersham for lunch or a drink at the nearby King’s Arms or the Griffin (now home to the ASK Italian restaurant), although it seems they were not able to accept as frequently as he would have liked. Machen often provided detailed (and familiar) travel directions, combined, in this instance from July 1930, with a brief pen picture of the state of the herbs in his garden:

The 3.25 from Marylebone is a handy train; and if your friend can come, pray bring him along. I am sorry we do not grow urtica pilulifera [the Roman nettle] here. But we have curious herbs: tansy, hyssop, marjoram, savory and rue. One or all of these might do good. But there is not any right Anticyran Hellebore.

As many people know, Old Amersham today is a very bunting-friendly town. This is not new either. In May 1935 Machen told his friend Summerford:

To use the idiom of a friendly nation: the Jubilee was a wow [ie the Silver Jubilee of King George V]. The roar of cheering coming over the wireless was tremendous. Amersham kept it up tremendously. [Machen’s daughter] Janet waited on six old men at the banquet for the aged and made it her pious care to fill and re-fill every glass with beer all through the proceedings. At night a torch light procession, a most famous sight, going through the street on the way to the Bonfire and Fireworks in the Park.

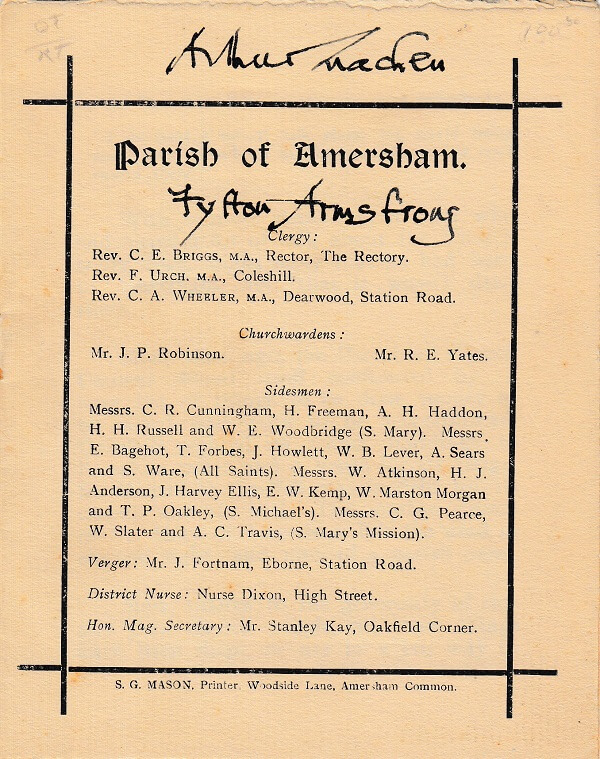

Machen clearly liked his new home and in 1930 wrote a booklet about the town for St Mary’s, his local church: Parish of Amersham (published anonymously in 1931). But, sadly, his finances remained precarious throughout the 1930s, although he continued to contribute small pieces to the newspapers. His letters are punctuated with comments on his minimal funds, the difficulty of getting new stories published, and, sometimes, direct requests for money. Machen’s one novel of the period was The Green Round (1933), in which the protagonist visits a Welsh seaside town but is followed home to London and plagued by a disruptive companion he cannot see. Machen’s “own opinion of it, in the process of writing, was so bad, that nothing but the sheer compulsion of £50 received on account could have made me finish it”. His friends did their best to help, his fan and biographer John Gawsworth being particularly active, arranging the publication of The Cosy Room and Other Stories (1936). Although it contained “things in it, dating from 1890, that make me sick to look at,” Machen contributed a new story, the puzzling N – in which a garden of unearthly beauty appears and disappears in Stoke Newington. The latter project motivated Machen to produce more new stories, which appeared as The Children of the Pool and Other Stories (1936), with tales of changelings, sinister children and mysterious rituals.

With the coming of the Second World War, concern was raised to a new level. Janet had travelled to America to visit friends before the outbreak and, thanks to their hospitality, remained there (she did not get back to Amersham until September 1941). Hilary volunteered for the army and served in France in 1940 – and was fortunate enough to return safely. Later that year, Amersham was too close to London to be completely tranquil during the Blitz. As Machen wrote to his old friend Waite in December:

Here, we often fall asleep to the drone of Geman planes; but so far, the old town remains undamaged and untouched. Mass in the morning is said in darkness, save for the two altar candles & the lamp before the Sacrament: there is a solemnity about the scene.

The end of the war brought relief for Machen with the return of Hilary who, after returning to the fray, spent almost three years in Italian and German prisoner of war camps. But old age was advancing relentlessly. In October 1946 Machen told Summerford:

I can see very little, I forget everything, and I never know where it is. ‘It’ = anything. Which reminds me somewhat of the last will and testament of Rabelais. I have nothing, I owe a great deal, and the rest I leave to the poor.

His wit, at least, was undimmed. But the sudden death of Purefoy on 30th March 1947 was a shattering blow. Machen received much attention from Hilary and Janet, and letters from Summerford, trying to cheer him as best they might. Machen ended one of his last letters, written in September that year, with the observation that: “The Fair is just over: to me a rather sad reminder of the old days.” Machen died on 15th December 1947 in St Joseph’s nursing home in Beaconsfield.

And what of Machen the man? A profile of him published in 1923 said: “Machen’s urbanity is that which develops into benignity with the years. When others are talking he listens with courteous attention. If anything tickles his fancy back goes his head with that loud laughter rarely heard among men. Learned without pedantry, a true scholar, his talk authoritative and enlivened by a fund of anecdote, a lover of life and the good things of life – never was man more remote from any form of nihilism! – dignified, polished, courtly.”

An almost-forgotten figure for too long, Machen has received increasing attention in recent years as readers discover him through writers he inspired, such as HP Lovecraft and Stephen King. In the age of ebooks, his writings are readily available and affordable – as are scholarly editions. On a very human level, this appreciation is evidenced by the scouring clean early this year of the tombstone above the grave he shares with Purefoy in St Mary’s Cemetery, Amersham. Previously darkened by age and lichen so as to be almost unreadable, its refurbishment was arranged by a society of admirers, The Friends of Arthur Machen. Now shining and legible, its very Machensque inscription has emerged from the shadows, yet remains appropriately enigmatic: Omnia exeunt in mysterium – “All things pass into mystery”.

Further Information

National Roman Legion Museum: museum.wales/roman

The Friends of Arthur Machen: arthurmachen.org.uk

The Life of Arthur Machen by John Gawsworth (edited by Roger Dobson) is published by Tartarus Press: tartaruspress.com