By Alison Bailey

From ‘aliens’ required to pay tax in the 15th century, European Jews escaping the Nazis, to more recent refugees from war-torn countries, Amersham has a long history in welcoming people displaced from their homes and forced to seek sanctuary abroad.

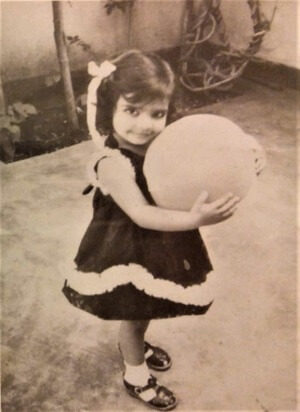

Sejal’s Story

Just over 50 years ago, Sejal Sachdev, a resident of Amersham for 25 years, fled her comfortable home in Uganda. On 23 October 1972, 7-year-old Sejal, her three brothers and her parents, arrived as refugees in a cold, wet Britain. President Idi Amin had given Ugandan Asians, who had lived in the country for three generations, just 90 days’ notice to leave. Sejal’s father, Manubhai had to make 18 visits to the British High Commission in Kampala, a dangerous journey of 130 miles, to obtain exit visas. After delays from the British Government and rising panic in Uganda, only a UN airlift ensured that all were got out on time.

Having sold or abandoned most of their possessions, the family arrived at Stansted Airport. A double-decker bus took them through London and out to East Sussex, then a journey of several hours. Sejal’s mom, Sudhaben, made the bus ride an adventure for the children, pointing out landmarks such as Big Ben and the Palace of Westminster. Sejal was too young to see her parents’ distress and just remembers the excitement. She now realises how brave they were.

The family’s home for the next few months was in the Maresfield Army Camp in East Sussex, one of 16 such camps run mainly by voluntary groups. Sejal said, “we were taken to a dormitory and were told that there were second hand clothes available. So, I rushed over to collect them, but my mother said that “we do not want second hand clothes”. She took them all back as she did not want any charity. They used to take us in the morning for breakfast and gave us cornflakes. But we did not eat that and were surprised that they put sugar on the cereals. We informed them that we were vegetarian, so they tried to prepare potato curry for us”. In November the family moved out to rented accommodation in London, but Sejal’s father, who had worked as a bank manager in Uganda, struggled to find work and this was a very difficult time for the family. In 1973 he secured a loan and purchased a post office and off-licence in Hertfordshire.

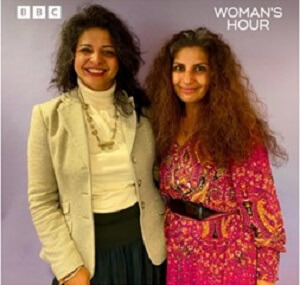

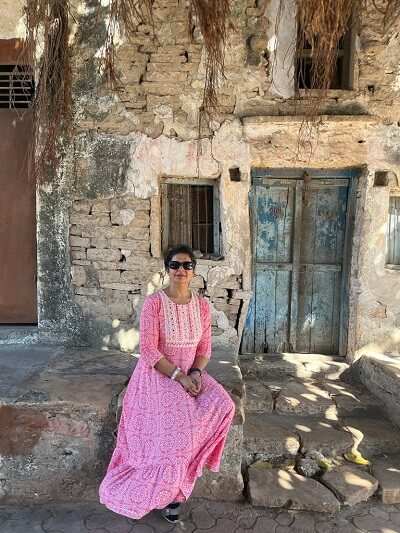

Like her siblings, Sejal went on to study at university and qualified as a chartered accountant before settling in Amersham to raise her own family. Her parents still live near Watford and feel very fortunate for their lives in the UK. “Being brought up in England afforded me opportunities I would not have had as a woman in Uganda. As a feminist and naturally outspoken, I have been able to express myself and marry the man of my choice” explained Sejal.

Ugandan Asians

Like the majority of the 28,000 Ugandan Asians that fled here in 1972, Sejal had a British passport. Despite an outcry from sections of the British press and the public, Britain had no option under international law but to admit its own nationals.

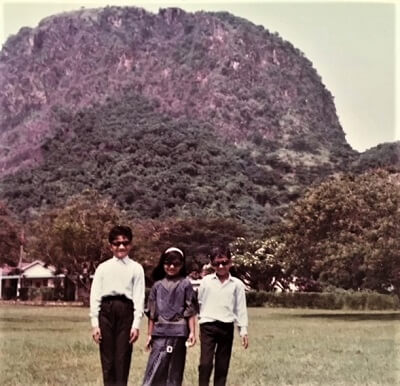

Uganda had been governed by Britain as a protectorate of the British Empire since 1894 and around 32,000 British Indians were recruited to East Africa under indentured labour contracts to construct the Ugandan railway. Sejal’s paternal grandfather, Gordhandasbhai, moved to Africa to work on the railway in the 1920s after leaving Gujarat because he did not want to farm his family’s land. Most of the Indians who survived the harsh working conditions returned home but nearly 7,000 stayed in Uganda, including Gordhandasbhai. He then opened a shop in Mulanda as a cotton trader before establishing a cycle shop in Tororo, where at the time there were only four Indians. Sejal’s father was born in Tororo in 1938.

Idi Amin

Uganda gained independence from Britain in 1962 and in 1971 General Idi Amin seized control in a military coup. Amin ruled Uganda as a dictator for the next eight years. In addition to forcibly removing the Indian minority, he carried out mass killings within the country to maintain his rule. An estimated 300,000 Ugandans died during his regime. The loss of Uganda’s Asians, who accounted for most of the tax revenue, sent the economy into freefall. Rampant inflation followed, and there were shortages of every kind.

Amin had initially been backed by the British. He had served in the British Colonial Army, the King’s African rifles. A heavyweight boxing champion and rugby player, Amin had a reputation for brutality and was among troops sent to Kenya to deal with the Mau Mau uprising. He reached the rank of sergeant-major, the highest rank an African could achieve under colonial rule. In 1960, in the run-up to Uganda’s independence, he was one of only two Ugandans to receive a commission.

Amin did part of his military training at Stirling in Scotland, and it is also believed that he attended the National Defence College at Latimer. Estate agent and local historian, Leslie Elgar Pike said that he let a house to him in Chesham Bois in the 60s. This is reported to be the flat above Mayo Brothers butcher shop, but I have never been able to verify this. Do contact me if you can help!