A Radical couple who loved the Chilterns

by Alison Bailey

“In March 1905 we pitched upon a small place at Chesham Bois by a delightful common and in the centre of innumerable field-paths and by-ways amongst the Chilterns. In every season, in fine weather and in bad, we roamed over the countryside, a land rich in historical memories and favoured by the affectionate care of Nature” wrote James Ramsay MacDonald, the first Labour Prime Minister in his biography of his wife, Margaret Ethel MacDonald. This was first published in 1912, just one year after Margaret’s early death.

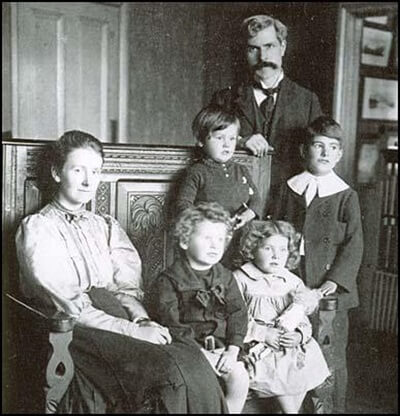

Margaret Ethel Gladstone (no relation to the Liberal Prime Minister) was a celebrated social reformer and suffragist. She married the Labour politician James Ramsay MacDonald, and their happy marriage produced six children. See also MacDonald Family.

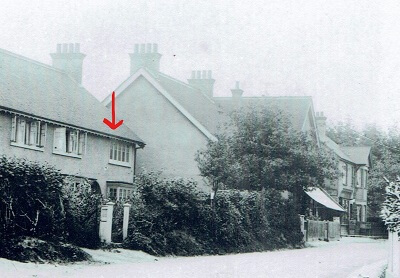

In Chesham Bois, they rented Linfield, a newly built Edwardian terraced house, next door to the shops in Bois Lane. This was a weekend home where the family could escape the stresses of political life in London.

Margaret was the daughter of a chemistry professor, educated at home, and at the Doreck College for Girls in Bayswater. She studied political economy under Millicent Fawcett (a leading campaigner for women’s suffrage recently honoured with a statue in Parliament Square) in the women’s department of Kings College. Known for her stubborn determination, she was remembered by Labour MP, David Marquand as having “no respect for middle-class convention, as she was certainly not prepared to wait meekly in her father’s house till someone came to marry her.”

Despite having independent means, she worked as a secretary at a nursing association in East London and volunteered for various organisations that helped the poor. Her experiences led to her becoming a socialist, influenced by the Christian Socialists and the Fabian Society. She joined the newly formed Independent Labour Party (ILP) and in May 1895 saw Ramsay MacDonald addressing an audience during his unsuccessful campaign to win the Southampton seat in the 1895 General Election. She noted that his red tie and curly hair made him look “horribly affected”. However, this did not stop her from giving a £1 contribution to his election fund and becoming one of his campaign workers. They then began meeting at the Socialist Club in St. Bride Street and at the British Museum, where they both had readers’ tickets, and were married in 1896.

Macdonald, a freelance journalist, from a working-class family in Lossiemouth, Morayshire, was educated at a Board school where he became a pupil teacher. He moved to London in 1886, working as a clerk, first for the Cyclists’ Touring Club and then for the Liberal MP, Thomas Louth. In his evenings he studied botany, mathematics, and physics at Birkbeck.

Margaret MacDonald’s private income financed her husband’s political career and with her support, he rose through the party ranks. It also enabled them to travel extensively to North America, India, Australia and South Africa. Macdonald established a reputation as a distinguished thinker and was elected MP for Leicester in 1906.

In turn, Macdonald encouraged Margaret’s political work and her campaigns for social justice. She served on the Women’s Industrial Council, organising the enquiry into home work in London, which was published in 1897. Chair of the Women’s Labour League, she was particularly concerned about the need for skilled work and training for women. She played a key part in establishing the first trade schools for girls in 1904. A supporter of women’s suffrage, Macdonald served on the executive of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.

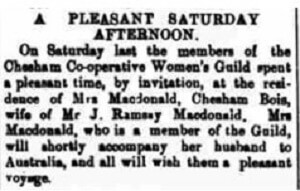

With their incredibly busy working lives it is understandable that that the MacDonalds wanted a rural escape for their expanding family. However, they soon took a keen interest in the working conditions of the local towns, speaking at local ILP meetings. In 1907 Margaret gave a talk in Aylesbury on woman’s suffrage and, in 1909, delivered an address in Wycombe in which she “strongly deprecated the present system which did not recognise the value of the work of women” who “were entitled to equal terms of renumeration with men”. Ramsay MacDonald served as a vice-president of the Cestreham Athletic Club with Lord Chesham and the Hon Walter Rothschild. Margaret was a member of the Chesham Co-operative Women’s Guild and hosted afternoon teas for members at Lindfield.

The local press took a keen interest in their activities, reporting on trips abroad such as a 1906 “autumn tour of the Colonies on account of ill-health”. It was Ramsay MacDonald’s health that was causing concern: “writing to his constituents, he states that the heavy strain of the last year or two has told severely upon him”. Ramsay, however, reached the age of 71 and it was Margaret who died first at the tragically young age of 41, from blood poisoning. The youngest daughter, Sheila was just a few months old.

Margaret hadn’t recovered from the death of their fourth child, David, the previous year. She wrote to a friend that “These statistics about mortality have become unbearable to me. I used to be able to read them in a dull scientific sort of way, but now I seem to know the pain behind each one. It is not true that time heals the pain. It doesn’t; it grows worse and worse. We women must work for a world where little children will not needlessly die”.

Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times and did not remarry. He always regretted that after, “she toiled through the early years with him, she did not live to see him come to his reward (as Prime Minister)”. Ramsay MacDonald remained a committed supporter of women’s rights and in his second minority government of 1929, he set the historic precedent of appointing the first female minister, Margaret Bondfield, as Minister for Labour.

In 1914 a memorial to Margaret was unveiled in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, close to the family’s London home. Now Grade II listed, the monument was apparently by Ramsay MacDonald, and sculpted by Richard Reginald Goulden. It consists of a bronze group depicting Margaret herself in kneeling posture, extending her arms lovingly around a row of playful children over a granite alcove seat. The words inscribed just below the bronze group are as follows:

“THIS SEAT IS IN MEMORY OF MARGARET MACDONALD WHO SPENT HER LIFE IN HELPING OTHERS.”

Margaret MacDonald features in Amersham Museum’s book Women at War, a celebration of our local suffrage campaigners and their contribution to WWI which can be purchased in the museum shop and online.

Sources

Margaret MacDonald (spartacus-educational.com)

http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/goulden/5.jpg

Margaret Ethel Gladstone MacDonald (1870-1911) – Find A Grave Memorial

Ramsay MacDonald: Biography on Undiscovered Scotland

Margaret Ethel MacDonald by James Ramsay MacDonald

British Newspaper Archive