Formidable Women of Chesham Bois in the 1940s

This article was written by Alison Bailey based on a 2015 talk she gave as part of Amersham Museum’s Homefires & Havens exhibition about the 1940s. It follows a talk she gave in 2014 on the Formidable Women of Chesham Bois during WW1

There is a long tradition of formidable women in the area but in the 1940s their contribution to the local community was vital. In contrast to their experiences during WWI, women were considered essential to the war effort in both civilian and military roles from the start of WWII. Conscription for women was introduced in 1941.

Three of the village’s Formidable Women of Chesham Bois during WWI have died Louise Jopling in 1933, Henrietta Busk in 1936 and Elizabeth Porter in 1940. However, Josephine and Car Richardson, the indomitable sisters living in the Tithe Barn, were both still full of energy and involved in every aspect of village life. In 1940 they are aged 71 and 67 respectively and are both Parish Councillors.

Their great nephew, Tony Voss, recalls: “My mother told me that if anything of significance was happening in the village someone would sound out the aunts about their views on the matter. They were, in effect, seeking planning permission from them!

During the war vegetables were grown in the garden of the Tithe Barn by the gardener known as ‘Buttercup’. It was his habit to walk to the Boot & Slipper at lunch time for his pint of cider and he often dozed the afternoon in a wheelbarrow. I remember being told “Don’t disturb Buttercup” and being fascinated by the bees visiting his beard as he slept, where, no doubt, they could find traces of the cider.

In those days there was an abundance of cherries from the various big trees and cherry parties were held so all could eat their fill. To keep the birds away there was a bronze bell in one tree, with a string running to the back door. One duty for Lizzie (Car’s companion) was to pull the string at regular intervals, whereupon a cloud of birds would fly out of the trees, I recall. I have the bell today”

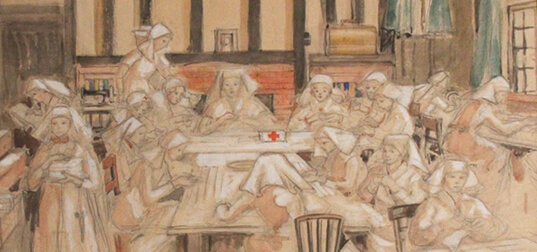

We know that that during the war the sisters are still working for the Red Cross. Their great niece Alison Naisby remembers seeing VAD working parties rolling bandages once again in the Tithe Barn. Car’s War Service Record shows that she provided injured service men at Amersham Hospital and the hospital at RAF Halton with occupational therapy, presumably painting.

It would seem they channeled their other interests, such as the Chiltern Art and Handicraft Club, into the war effort as well. From the Bucks Examiner we learn that in April 1944 Car held an exhibition of her watercolour drawings at St Michael’s Hall in aid of the Red Cross. The exhibition consists of 80 landscapes of Italy and occupied countries – “several of which are of places in Italy at present figuring in our war news. All are typical of this talented artist’s style – the finesse of the detail and true ‘atmosphere’ of which is so well known locally and in wider art circles”. It raised £60. “Most satisfactory was the steady stream of visitors – busy shoppers, soldiers, interested children who found time to come in again and again.”

The Tithe Barn was still at the centre of village social gatherings. Again from the Bucks Examiner we learn that April 1944 the Tithe Barn garden was opened to the public to raise similar funds “And visitors had the added pleasure of viewing, in the lovely old raftered studio, some of Miss Car Richardson’s sketches, those depicting beauty spots in the Amersham district”.

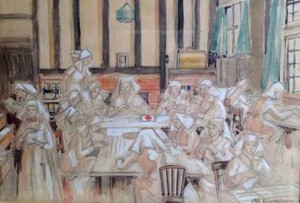

During the war Car was commissioned  to paint windmills from all over the country including Lincolnshire, Suffolk, and Norfolk. She also painted local historical buildings and churches for the Bucks Archaeologists Society. It is believed that this was in response to a national appeal for photographers, architects and artists to record buildings of historic interest. The National Buildings Record was set up in 1940 under the inspiration of Walter Godfrey, its first Director “to meet the dangers of war then threatening many buildings of national importance”. Bucks County Museum has a collection of 38 of these paintings including watercolours of St Leonard’s Church and Old Amersham.

to paint windmills from all over the country including Lincolnshire, Suffolk, and Norfolk. She also painted local historical buildings and churches for the Bucks Archaeologists Society. It is believed that this was in response to a national appeal for photographers, architects and artists to record buildings of historic interest. The National Buildings Record was set up in 1940 under the inspiration of Walter Godfrey, its first Director “to meet the dangers of war then threatening many buildings of national importance”. Bucks County Museum has a collection of 38 of these paintings including watercolours of St Leonard’s Church and Old Amersham.

Josephine was elected President of the Chiltern Art and Handicraft Club in 1941 and held the post until her death in 1945 and Caroline was elected President in 1955 until her death in 1959.

When Queen Elizabeth visited the area in 1941 she met Josephine and Car in recognition of their work for the Red Cross. We know the Queen also met the local Women’s Institute at Hyde Heath. The WI movement goes back to 1915 and is currently celebrating their centenary. Despite the Hyde Heath WI being established in 1919 the movement was still in its infancy in this area in 1940. Old Amersham didn’t have a WI until 1948 and Amersham Common until 1949. Chesham Bois had to wait until 1969.

As in WWI the term ‘Home Front’ was frequently used, acknowledging the women’s contribution to the war effort and the battles that were being fought on a domestic level with rationing, recycling, and war work.

The men were often away at war and as the allowance paid to a soldier’s wife was meagre, it was a difficult battle to put food on the table. Even with ration books food was not readily available.

With Dinah Latham’s father, Roland, serving in France she recalls how her mother, Eleanor Hatchett, kept chickens, storing their eggs in isinglass. “There were always dead rabbits and pheasants hanging in the walk-in larder and my mother was always plucking or skinning something!” Dinah recalls how nothing was ever wasted, food, material, wool everything was recycled. “I remember clothes coupons being saved …. also learning to knit and using darning wool to knit with because it could be purchased without those coupons. The problem was the colours were so dreary … black, brown and dark grey are all I remember and the wool was thin so took lots of knitting and was very scratchy to wear. “

Shop fronts were often empty for lack of items to sell. They had sandbags piled in front and if there was a rumour that the grocer has oranges in, queues of housewives and children formed along Chiltern Parade for the rare treat. Close to the Regent Cinema (a vital part of local social life at the time) there was a Wartime Food Office where ration books were issued to every single adult and child. Every six months people had to be issued with a new book. There was a siren on the corner of Sycamore Road and Woodside Road that was used to warn of air raids. After the war it was used to call out the fire brigade. A shelter was built in October 1940 to accommodate fifty people.

Lola Richard’s (née Matto) childhood recollections show that she had similar experiences to Dinah. Her father initially served as an Air Raid Warden and later joined the Army, serving in India and Burma. Her mum, Mrs Matto ‘kept the home fires burning’. She kept chickens and rabbits to augment the food rations.

Suzanne Matto (née Reddick) was a very glamorous French lady, whose house L’Enchantresse in Bois Lane was presumably named after her. Her mother, Alice Reddick had a successful millinery business in Paris and London and she travelled extensively between both cities as a model and concert pianist. She met her husband, Edward Matto, a handsome Italian who worked as a commercial artist for the Daily Express, when they were both taking part in a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. They left London for Chesham Bois during the war.

Lola recalls “The worst part for people like us were the air raids. My Dad constructed an air raid shelter in the house, made from a heavy carpentry bench, with sheets of metal encasing the sides. We crawled into the shelter from one end, and had blankets and pillows in there as we often had to hide for quite a while. The only problem was, as soon as the siren sounded, our 3 large Airedales would dash for the shelter and get in before us! They had to be hauled out again by their tails – the only part that was left outside – before we could clamber in ourselves!!

We would listen to the planes going overhead, and got to know by the sound of them whether they were ‘Ours’ or ‘Theirs’. I very clearly remember the jumper that my Mum was knitting for me in there. It was a complicated Fair Isle pattern, no doubt chosen to take her mind off the bombs. For light, we had a lantern covered with green baize, and I can still recall the smell of the warm cloth. Of course black-outs were in effect all over the country (so the enemy could not identify places so easily) – so we couldn’t have much light, even tucked away in the shelter. As a child I was only aware of feeling safe and protected in our hide-away.

When the All Clear siren sounded, it felt so wonderful! We would all pile out and my Mum would go and put the kettle on to make a cup of tea!! “

“However, one night it was different. Shortly after an especially scary raid, my Mum was alarmed by the Bomb Disposal Squad leader pounding on our door and telling us to evacuate the house quickly. Evidently, they knew that one bomb had dropped but had not exploded yet! A German bomber had dropped a ‘stick’ of six bombs. One was a direct hit on the goat shed at the far end of our property – the poor goat never knew what hit him! The next one fell in our back lawn – only yards away from where my Mum and I were hiding in our home-made shelter. Not only did it land there, but it turned underground and tunneled beneath the house……but did not explode!

After evacuating us, the Bomb Disposal Squad dug down to defuse and extricate the bomb. I have the greatest admiration for those brave men! We were not allowed back home officially, but my Mum sneaked back to feed the rabbits and chickens, and managed to get some photos of the crew working. After the crisis was over she made them all a cup of tea, of course! “

This bombing raid had a major impact on the village causing more property damage – particularly to the stained glass in St Leonard’s Church and 5 Anne’s Corner. Sadly this wasn’t the only bomb attack on Chesham Bois. Just before 11am Sunday 2nd July 1944 a V1 rocket hit and demolished Red Leys and its adjoining bungalow and caused wide spread damage to surrounding properties in Chestnut Lane and all over the area.

The Bucks County Council’s article ‘Bucks in WWII’ contains the report of the Area Engineer Richard Harris who was on site within half an hour of the explosion. He describes how around 200 people were involved in the rescue with teams from Amersham, Chesham and Great Missenden forming 10 chains of 15 men to pick through the debris. There were 20 casualties in total, 3 were killed, 5 taken away in ambulances, 10 in cars and 2 walking. Red Leys was demolished on impact, 3 further properties had to be demolished and some 300 other properties suffered damage. The Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) organised a mobile canteen providing hot drinks and lunch for the workers and brought blankets and clothes for the injured.

One of the 3 dead was an 18 month old girl Christina Hanbury-Sparrow, who is buried in Chesham Bois Churchyard. The grave stone is also dedicated in loving memory of her half-sister, Gisela, age 19, killed in an air raid on Dresden in 1945. The Tenor Bell in St Leonard’s Church is inscribed Christina and Gisela 1947 and was presented by the family to replace the cracked Tenor Bell which is in the Museum today. Christina’s father Lt Colonel Hanbury-Sparrow, 6ft 8” tall was a hero in WWI, twice mentioned in despatches, he’d been awarded the Distinguished Service Order twice and the Military Cross. He wrote a highly regarded book of his experiences The Land-Locked Lake but was rejected by the army in WWII because he was married to a German.

One of the 3 dead was an 18 month old girl Christina Hanbury-Sparrow, who is buried in Chesham Bois Churchyard. The grave stone is also dedicated in loving memory of her half-sister, Gisela, age 19, killed in an air raid on Dresden in 1945. The Tenor Bell in St Leonard’s Church is inscribed Christina and Gisela 1947 and was presented by the family to replace the cracked Tenor Bell which is in the Museum today. Christina’s father Lt Colonel Hanbury-Sparrow, 6ft 8” tall was a hero in WWI, twice mentioned in despatches, he’d been awarded the Distinguished Service Order twice and the Military Cross. He wrote a highly regarded book of his experiences The Land-Locked Lake but was rejected by the army in WWII because he was married to a German.

Alan Hanbury-Sparrow had met his second wife, Amelie, a divorcee with 2 young children, when she was visiting relatives in England in 1936. He wrote about her “alert green eyes and quick wit”. They lived in Hamburg in the years leading up to the war and his step-son Juergen Corleis writes very fondly of ‘Uncle Alan’ in his memoirs Always on the Other Side. He describes those years in Hamburg as the happiest of his life.

Amelie Hanbury-Sparrow had divorced her first husband, an officer in the German army, in 1933 and had brought up her son and daughter as a single parent. However when she married Alan Hanbury-Sparrow her ex-husband demanded the children back. Whilst he had had very little to do with them since the divorce he knew it would be too damaging for his career to have his children brought up by an English man. He had already had to prove to military command that his ex-wife was Aryan – embroidering the facts in the process as Amelie had a Jewish maternal grandmother.

Amelie took her husband to court for custody of the children but lost the case because the judge told her she should have married a German. 9 year old Juergen and 13 year old Gisela were sent away to their father who immediately put them into boarding schools as he had no room for them in his home. They were forbidden to have any contact with their mother or their mother’s family. The Hanbury-Sparrows left Germany because it was no longer safe for them to remain and initially settled in America but when Amelie fell pregnant in 1942 they decided to travel to the UK. In his Memoirs Juergen quoted Amelie as follows “Now it was overwhelmingly clear to us that we simply had to find a way of getting back, for we belonged to Europe and Europe’s fate was our fate. Alan English, I German and our child American that didn’t seem right.”

They took a passage on a small freighter carrying war supplies at the height of the U-Boat battle of the summer of 1942 just after America had joined the war. Their freighter was part of a convoy of several small ships and 2 torpedo-boats. 3 freighters were sunk in the convoy but their ship kept going until Liverpool.

Christina was born that December in Chesham Bois and tragically killed 18 months later. During the war Juergen learnt about the death of his baby sister from his mother because she had found a way of smuggling letters to him via a Swedish friend. Then a year later news reached Amelie that her eldest daughter was also dead – in the bombing of Dresden.

Following these tragic losses, the Hanbury-Sparrows decided to adopt. In 1945 they adopted twins Angela and Andrew whilst they were living at Elangeni with their good friends the Crovos who took them in after their home had been destroyed. Lt. Col. Hanbury-Sparrow was posted to Germany in charge of Agriculture at the British Control Commission after the war where he was able to make contact again with Juergen and Amelie’s mother who had both survived. Amelie and their young adopted children joined him the following year. They returned to Amersham six years later, where they bought ‘Mansfield’ in Hollybush Lane and settled there until they emigrated to Australia in 1969 following the twins. Juergen, a distinguished journalist, foreign correspondent and documentary maker also later joined them in Australia. His 1985 documentary on the Holocaust is a permanent feature at the Bergen-Belsen memorial, and has been seen by millions of visitors. Amelie passed away in Australia at the age of 98.

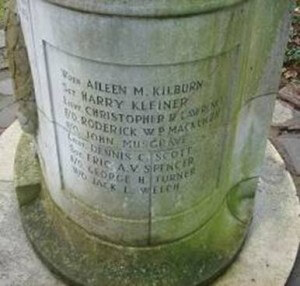

Sadly Christina Hanbury-Sparrow wasn’t the only Chesham Bois resident to die as a result of the war. Our War Memorial lists 18 dead, 17 service men and 1 service woman.

Chesham Bois War Memorial showing Wren Aileen Kilburn’s name at the top

Wren Aileen Kilburn was just 18 when she was killed by a bomb in Great Yarmouth March 1943. She was the daughter of Charles and Elsie Kilburn of Trewithin, Stubbs Wood and is buried in the Chesham Bois Burial Ground.

She had answered the WRNS recruiting call “Join the Wrens – free a man for the fleet” and after training was sent to HMS Midge, a Coastal Forces Base in Great Yarmouth. On 17th March 1943, there was an air raid. In bad weather at 6.28 am a lone Luftwaffe Dornier flew over the south part of Great Yarmouth and dropped six bombs. One scored a direct hit on a WRNS hostel. The house was destroyed and fire broke out.

Roger Cook, whose research on our WWII war dead can be found here (download), found the following account of the raid by Olive Swift of HMS Midge: “the bombing was devastating; a lot of the service quarters were razed to the ground, including our own. I was sleeping in a top bunk, but found myself blasted from my bed, lying on the floor at the far end of the room, amongst a lot of rubble and glass. It was fortunate for me that I was not in my bed, as a large section of wall and a window fell on it. There were seven of us in the cabin, and I can truthfully say that nobody panicked, we had great faith in our naval friends, they dug us out alright, and if they hadn’t got a spade, they dug with their hands. Fire broke out, and being short of fire engines, we formed a chain, and passed buckets of water along, from a stand pipe. When the losses were made known, we found many of our friends were injured, or in shock, and had to be sent home. Worst of all, seven Wrens and our Officer was killed, but war time is no time for brooding and we survivors attended a memorial service for our dead comrades, and went back to work”.

Locally women were fighting the Nazis in many other ways. Patricia Panton was married to a solicitor Alistair Panton. They lived in ‘Thornbury’, Manor Drive and then moved to Orchard House North Road after the war. Patricia worked for the War Department, based in Wormwood Scrubs. According to Patricia’s son she eavesdropped on conversations including those of the exiled Duke and Duchess of Windsor. I’ve not been able to corroborate this exactly but it is well known that the Duke and Duchess were suspected of collaborating with the Nazis and were under surveillance by British Intelligence and the FBI. MI8, Radio Security Section, was at the time based in the prison and monitored intercepted signals, with the intention of picking up enemy agents so the family story may well be true.

In 1947, Patricia who was an extremely athletic and active lady fell dangerously ill with polio. Pregnant at the time, she was in hospital in Oxford for several months and Christopher, her third son was born there. Thereafter she was confined to a wheelchair but this didn’t stop her living life to the full though according to her son. She had a specially adapted car, kept dogs, runner ducks and went on to have a greatly wished for daughter against doctors’ advice.

Susan Lustig, née Cohn, from Breslau (then in Eastern Germany and today in Poland) fled to England in 1939, aged just 18. Susan’s father had recently died, he had served in the German Army in WWI and unusually for a Jew had been made an officer and was awarded the Iron Cross 1st class for bravery.

This did not prevent Susan from suffering anti-Semitism after the Nazis had come to power. A school pal asked her to correct her French homework and then said that she would drown her during swimming lessons if she left any mistakes. When Susan complained about it to the Headmistress, she received the reply “if you don’t like it, you can leave the school”. Later she had to go to a special Jewish school when Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend German schools. After ‘Kristallnacht’ November 1938 her mother realised that she had to get Susan out but she was too old to be included in the Kindertransport as she was over 16 and too young for a visa as a domestic servant as she wasn’t yet 18. So she had to wait until her 18th birthday in April 1939 before applying for a visa and getting a UK family to sponsor her. Women were admitted to the UK only as domestic servants or trainee nurses with a guarantee of work – there was no other option.

Life was not easy in London as a refugee, especially after war broke out and her employer dismissed her that same day as she didn’t want a ‘German’ servant in the house. She must also have been extremely worried about her mother as she was unable to leave Breslau. She had an Affidavit to go to the USA, where she had a brother, but there was a quota according to your nationality, and after that had been filled, you were given a “waiting number”, which in Susan’s mother’s case was so high that it would have involved a wait of several years. In fact, a letter from the German steamship Company HAPAG turned up after the war which informed some authority that a ticket for the mother was now available, but she could not be traced! It had been sent after her mother’s death in a concentration camp.

In England Susan was called up for war work and joined the women’s ATS, the Auxiliary Territorial Service. She initially worked as a dental orderly, and then as a medical orderly – when she spent 3 months de-lousing ATS girls!

However her war took a really interesting turn in 1943 when an émigré friend who worked at Latimer House recommended her for the Intelligence Corps. After a selection interview and various tests she was given a railway ticket to Chalfont and Latimer station.

“A very smart naval officer and his driver waited for me in a jeep outside. As I got into the car the driver said to me, “I bet you a packet of cigarettes that you’ll be a Sergeant by tonight” I didn’t believe him. That night I was unexpectedly promoted to Sergeant and I owed him a packet of cigarettes!”

We now know, although Susan didn’t, that she was working at Latimer House, one of 3 Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centres, where German and Italian prisoners of war were held, interrogated and eavesdropped on. Latimer House was the HQ of Colonel Thomas Kendrick of Military Intelligence (MI6) who ran the unit which in turn became MI19. Masquerading as a supply depot, known as No.1 Distribution Centre no one locally knew its true activities. Even Parliament did not know of its existence. This unit became one of the most valuable sources of intelligence on German weapons – particularly V1 and V2 rockets, flying bombs, jet propelled aircraft and submarines. The intelligence gleaned at Latimer and its sister sites aided the intelligence from Bletchley Park and enabled Britain to win the war.

Susan, based at Latimer House and then later at Wilton Park in Beaconsfield (the 3rd centre was Trent Park in Cockfosters) worked on prisoners’ personal highly classified intelligence files. At one time she came across the papers of her former English teacher from Breslau who was being held in the camp. She ‘put in a good word for him’ as she knew he was not a Nazi and ‘he was soon transferred’.

It was at Latimer House, at a Christmas party, that she met her future husband, Fritz Lustig also a German refugee who was one of the secret listeners working in the ‘M Room’, listening in and recording the conversations of prisoners of war in their cells. Their romance started though when Fritz, a talented cellist was playing in a concert at Wilton Park accompanying a rather awful singer and Susan took pity on him as he looked so glum and with a friend she invited him for a drink to cheer him up. The romance blossomed and they became secretly engaged. By now Fritz was based in Latimer House and Susan in Wilton Park so on their days off they either used the small army car that was a shuttle between the 2 centres or they cycled to meet each other half way. They also sent each other many notes via the regular dispatch rider.

When the war ended they decided to get married immediately as Fritz could be transferred to Germany on similar intelligence work (which is exactly what happened). They had to ask Kendrick’s permission as they had both signed the Official Secrets Act. Susan was still on duty the day before so Fritz prepared all the food and they were married in June 1945. Fritz was indeed sent out to Germany that September and Susan was discharged from the ATS having gained the rank of Staff Quartermaster Sergeant (equivalent to Sergeant Major in the Army). Armed with an excellent reference from Kendrick her first civilian job after the war was with the United Nations.

Fritz was finally demobilized in June 1946 and able to return to England and Susan. They received British nationality, settled in North London and were happily married for 67 years. They had two sons, Robin, a distinguished journalist and Radio 4 presenter and Stephen who works in publishing.

Amazingly for the first years of that marriage they never discussed Latimer House, and never told their sons anything. It was only after the first books about Bletchley Park started to be published that the Lustigs began to think that the Official Secrets Act might no longer apply although they received no official notification. If asked they then began to talk about their experiences but Fritz says they never ‘volunteered’ such information. A chance meeting with Helen Fry led Fritz to tell her their story and then to her detailed research in the now mainly declassified archives and to her publishing her books The M Room and Spymaster, the secret life of Kendrick. Sadly Susan didn’t see the latter published as she died in March 2013 but Helen remembers Susan’s ‘absolute delight’ in attending the launch of The M Room and her pride in being one of the 3 veterans present (Fritz was there also) receiving ‘public recognition for their extraordinary contribution to the war and the defeat of Nazism’.

As you can imagine one of the major impacts of the war on the area was the influx and of new people – the very many servicemen and women billeted locally or in camps, the hundreds of evacuee children, the many displaced families, and of course the refugees.

These were mainly European Jewish refugees and together with the British-born Jewish evacuees, the handful of Jewish families who’d been in the area for generations and the many domestic servants living locally, they formed a vibrant community in the area. They even established their own Synagogue in Woodside Road. [The material about the Jewish refugees in this article comes from Vivien and Deborah Samson and their book: (2015) The Rabbi in the Green Jacket: Memories of Jewish Buckinghamshire, 1939 – 1945, England: Matador.]

These new arrivals of course included many formidable women and they quickly became well integrated into the district, serving on numerous committees, fundraising and contributing to the war effort in many ways -air raid wardens, firewatchers, members of the WVS, making barrage balloons at the Maltings. They welcomed Jewish servicemen into their homes for Shabbat and the High holydays and provided them with a social club and kosher canteen, they gave homes to the many (around 300) Jewish children who were evacuated from London schools. They also ran a canteen in the Pioneer Hall where children could get a good dinner for 4d, and adults for 1/-. There were cake baking competitions to raise funds and one refugee claims the Jewish ladies won every time!

Esther Kleiner of Dorset House, Long Park was one such women who joined the WVS and got involved in all the committees, the jam making and so on. She organised a knitting group to make balaclavas, gloves, socks and anything else the soldiers might need. Her son, Sergeant Harry Kleiner, was a flight engineer on a Lancaster bomber when it was shot down over the North Sea. He is commemorated on the Chesham Bois War Memorial.

Sister Katie Krone worked tirelessly in Amersham Hospital. She helped transform the Old Amersham workhouse into a hospital during the war. She was another German Jewish refugee whose family were all murdered. Unlike many others who moved back to London after the war she stayed on in Amersham Hospital. She was a strict nursing sister but was always very caring and is very fondly remembered.

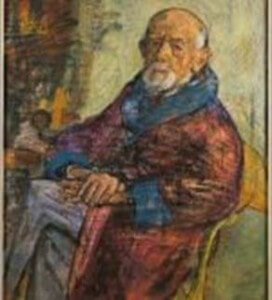

Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, a distinguished Austrian painter and the subject of the book The undiscovered Expressionist by Jill Lloyd came to live in Chesham Bois during the war. A pupil and lifelong friend of Max Beckmann she was forced to leave her native Vienna and a promising career by the rise of National Socialism. Here she rebuilt her life, to become one of the major Austrian painters of the twentieth century and one of the most important émigré artists in her adopted homeland.

Her work includes several hundred drawings and 300 paintings, mostly portraits, self-portraits and still-lifes, a number of which she completed in Amersham. These include portraits of local people such as Father Milburn of Durris, Stubbs Wood where she initially lodged. She also painted the garden in Chestnut Lane where she lived with her mother and local rural scenes.

Copyright in these three pictures is held by the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust 2015.

Marie-Louise was the lover of Elias Canetti, winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize for literature who also sought refuge here with his wife Veza and wrote his impressions of Chesham Bois in his book Party in the Blitz. Canetti’s huge collection of books was kept in Marie-Louise’s studio. Together they were quite an ‘artistic set’ with the Colensos of Elangeni, the Milburns, composer Francesco Ticciati of Chestnut Lane’s Music Studio, the Brailsfords, various members of the Chilterns Arts and Handicrafts Club and The Hanbury-Sparrows. Indeed Canetti mentions the Hanbury-Sparrow’s story in Party in the Blitz – although he does get some of the details wrong.

During the war housing all these new people was a real challenge for the local billeting officers. If anyone had spare rooms these were soon occupied by evacuees and refugees. Many families shared the same house or had to live in unlikely places such as the Amersham and Chiltern Rugby Clubhouse and the Chesham Cricket Club pavilion. Both were used to house Jewish families during the war.

When the war ended many decided to return to London but for those families who wanted to stay in the area finding suitable accommodation was a real problem. The area had a number of temporary army camps with Nissen huts wooden huts and ablution blocks which had been used as barracks for troops in training or in transit and as the soldiers moved out displaced families started to move in.

Elizabeth James, now Barry, another formidable woman, moved into Beech Barn Camp, the “squatter camp” in Chesham Bois, with her 2 young children in 1945. She had been abandoned by her husband who was serving in the RAF and had been living for a time in a tiny caravan in Amersham with her brother and his family.

When she first arrived at the camp she was met by Margaret Hartley, a member of the Committee. Margaret explained that there were no huts available but ‘to get one’s foot in the door’ they could live in the dance hall. To furnish this huge space she only had the children’s cots, an army canvas’ fold-up’ single bed, an old chest of drawers and a couple of orange boxes from the general store round the corner.

After getting a hut, Elizabeth describes how tough that first winter was living in a wooden hut with blankets for walls: “During one winter there was thick ice on the inside of the windows, but I still had to get the children up and take them to work with me, walking a couple of miles in the deep snow to earn enough money for milk, bread, and potatoes. I would carry Valerie as far as I could. David would come strolling leisurely behind, with me nagging him to ‘get a move on, or I would be late for work’. It seemed a long way to go just for two hours work for three shillings, but the journey was soon forgotten when we were settled back home, with a hot meal on the table. On the way home I would pick up wood from the hedgerows, although it was hard to find in the deep snow. On such days, not only did we have a meal – we also had warmth from the fire.

Being a deserted wife, it wasn’t easy bringing up two children on my own. At that stage there were no pensions or parent’s allowance, one had to work hard, otherwise starve. Although there was ‘The Relief’ one could go to, as a last resort, where we would be given a food voucher.”

David James’ memories of these awful winters show what an amazing job his mom did: “We spent a lot of time indoors due to the bad weather and there was always a lot of good things to do. Mum could tinkle a dozen tunes on an old piano we’d acquired from somewhere and she was good at reading books to us and playing games. We could also keep ourselves amused. The games were always played amid much laughter and squeals of delight. The winters always went as fast as the busy summers.”

After successfully campaigning with the Hartley’s for Amersham Council to take over Beech Barn Camp the family moved in to one of the refurbished Nissen huts and lived in the camp until 1953. Today they live in Australia and Elizabeth is still going strong at the age of 95.

Wladzia Pogoda, now Tanska lived in the Polish resettlement camp at Hodgemoor Woods for 10 years. She met her husband and started her family there.

In 1940 as an 11 year old girl she was forced to leave the family farm and was transported to Siberia in a cattle wagon with her parents and 3 year old sister when the Soviet Army invaded Eastern Poland. There then followed 8 years as a homeless refugee. During this time they travelled to camps in Uzbekistan, Iran and the Lebanon, often in horrific conditions. She describes the journey to Iran packed on a boat “like sardines” – which sounds horribly familiar. At one time she was placed in an orphanage because her parents were so ill with typhoid, they recovered but sadly her little sister died. Against all the odds Wladzia and her parents arrived in England as refugees 12 September 1948. They were unable to return to Poland as their homes had been annexed by Russia under the political settlement at the end of the war. Wladzia was issued with a ‘Polish’ identity card but this was not recognised by the communist government in Poland. It authorised her to travel anywhere except Poland!

Hodgemoor provided a safe home to over 150 Polish families after the war in temporary buildings, barracks and Nissen huts. Conditions in the camp were basic but it was a proper community, a Polish village with a Church, with its own priest, an infant school, a post office, a shop and an entertainment hall used for meetings, plays, and celebrations.

Wladzia and her family settled in this area. She has written her memoirs for her 3 children, grandchildren and great grandchildren and has been happy to share her memories with the Museum’s Knit and Natter group.

The post-war housing crisis was ameliorated by the 1945-51 Labour Government’s provision for the building of council houses, legislated for in the New Towns Act of 1946 and the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. The Hartleys moved to a council house in the new town of Hemel Hempstead in 1950 and the Tanskas to a council house in Little Chalfont in 1958. Other families were relocated to Piggotts Orchard in Old Amersham and the Quill Hall estate.

David James remembers the morning in 1953 when at last a letter dropped through the letterbox of 16 Beech Barn. “When Mum opened it she jumped for joy, we’d been allocated a house in Weller Close the very area where all our friends were.”

Bibliography

Walking Forward Looking Back – Dinah Latham

The M Room – Helen Fry

Spymaster, the secret life of Kendrick – Helen Fry

Always on the Other Side – Juergen Corleis

The Undiscovered Expressionist, a Life of Marie-Louise von Motesiczky – Jill Lloyd

Party in the Blitz – Elias Canetti

Buckinghamshire Spies and Subversives – DJ Kelly

The Rabbi in the Green Jacket, Memories of Jewish Buckinghamshire 1939 – 1945 by Vivien and Deborah Samson