Shakespeare and “William Cheynie of Chessamboyes” – A Mystery Solved

By Nick Gammage, Jan 2024

Unlocking the secrets around a shadowy Tudor figure known as “William Cheynie of Chessamboyes” presents us with a clearer picture than was known before of the link between William Shakespeare, the glittering court circles of Queen Elizabeth I and Lollardy in this part of the Chiltern Hills.

I first came across William Cheynie during my research to recreate William Shakespeare’s walk from Stratford upon Avon to London in the mid 1580’s which in all likelihood would have brought him through Amersham. I discovered that his patron Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, was grandson of Jane Cheyne, 1st Countess of Southampton, who according to the Wriothesley Memorial at Titchfield was the daughter of “William Cheynie of Chessamboyes”.

Piecing together long-lost fragments from the history of the Cheynes of Chesham Bois it is now possible to answer the question ‘who exactly was this mysterious William Cheyne?’

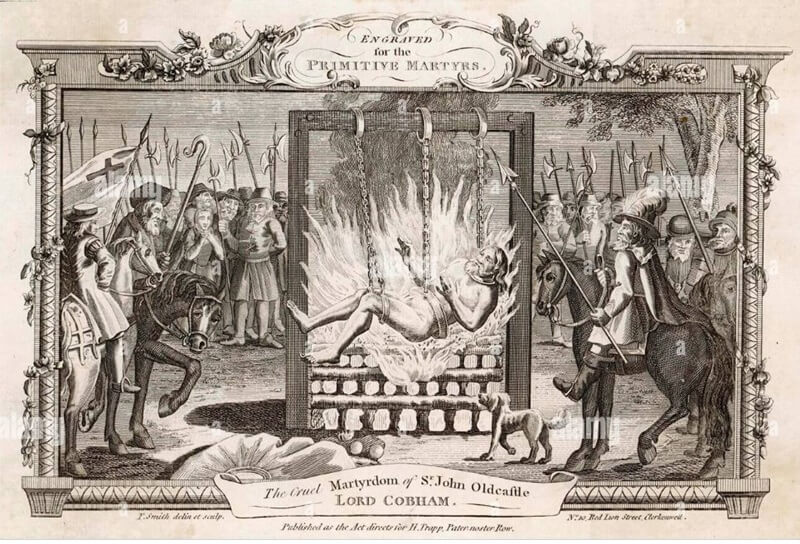

The solution reveals powerful bonds between the Lollard-supporting Cheyne family and the great Lollard families of the West Country including a family link between the Cheynes and the Lollard leader Sir John Oldcastle (c. 1374 – 1417), burned at the stake as a heretic. (1)

The mysterious figure of “William Cheynie” rose up while I was researching William Shakespeare’s journey of around 1585 when he left his Stratford Upon Avon home for a new life in the London playhouses – a journey which itself was shrouded in myth and mystery and which would have brought him through Amersham.

William Shakespeare’s great patron and close friend was the powerful courtier Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624) (2). I discovered that Wriothesley’s grandmother, the 1st Countess of Southampton, was in fact Jane Cheyne (1505-1574) born and brought up in rural Buckinghamshire at Chesham Bois Mansion.

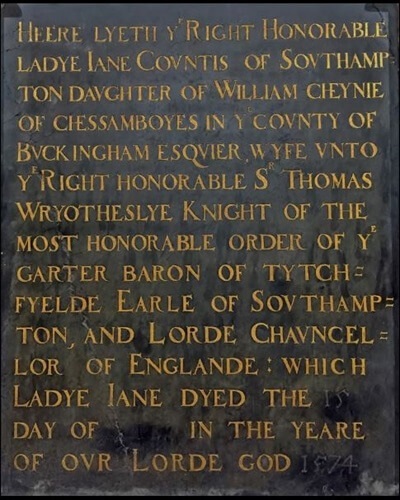

Jane Cheyne Wriothesley’s (pronounced “Rithsley” (3)) deep influence on her family is clear from the magnificent memorial to her in the church on the family estate at Titchfield in Hampshire which shows (very unusually for Elizabethan Memorials) the Matriarch on top, her husband and son below.

The memorial tablet carries a reference to Jane’s Chesham Bois origins:

“Heere lyeth ye Right Honourable Lady Jane Countis of Southampton daughter of William Cheynie of Chessamboyes in ye Countie of Buckingham Esquier.”

William Shakespeare must have seen that memorial when he stayed with his friend the Earl of Southampton at Titchfield. It was erected in 1594, 20 years after Jane’s death, exactly the time that Shakespeare was dedicating some of his greatest poetry in loving terms to his patron Henry Wriothesley.

Shakespeare may well have read the inscription and wondered about that place with the strange sounding name – “Chessamboyes.” It is believed he travelled widely with the Earl of Southampton and he may well have joined him on visits to his grandmother’s family at Chesham Bois.

The life of Jane Wriothesley, Countess of Southampton is well-documented. The long history of the Cheyne family who first arrived in England with William’s army in 1066 has, equally, been well-charted. Much has been written about the branch of the Cheyne family which settled at Drayton Beauchamp and Chesham Bois including two brilliantly researched pieces by the late Chesham Bois historian Anne Paton (4). But it is a very different story with Jane’s father, William of whom so little has been known.

First Son of Powerful Chesham Bois Tudor Landowner

William must have had some influence and standing: in 1530 his daughter Jane was married to Thomas Wriothesley, a young courtier on the cusp of a meteoric rise to become one of Henry VIII’s most trusted allies, whom Henry rewarded first with the gift of former church lands at Titchfield and then with the new title 1st Earl of Southampton and Baron of Titchfield.

There were just a few small clues to his life which have proved just enough for us now to understand for the first time when exactly William lived, how he came to be married into one of the great Herefordshire families, how his daughter could have married someone of such latent power in Thomas Wriothesley, and why there has been so very little recorded about him.

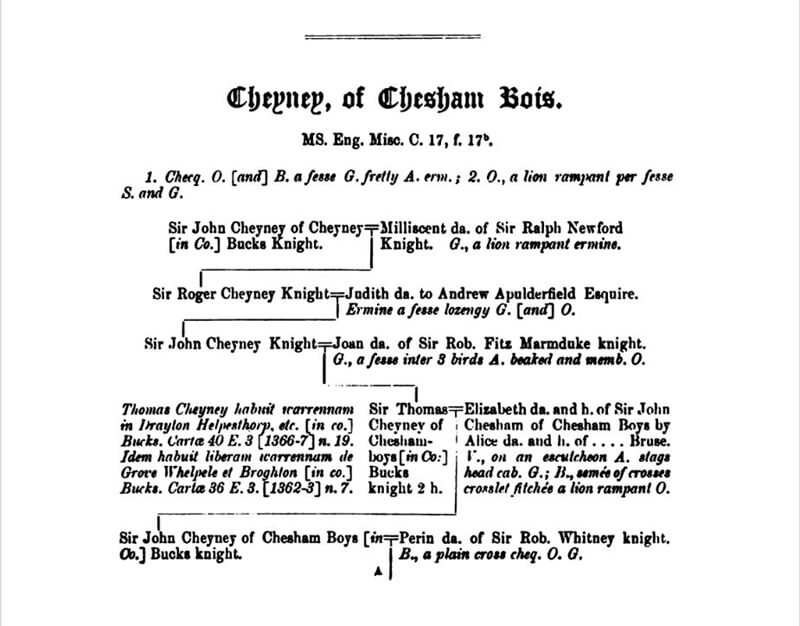

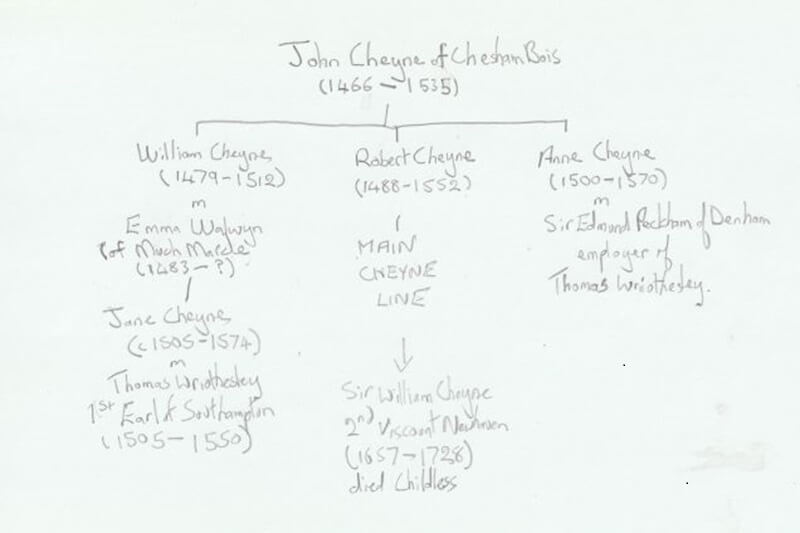

The clues come through the work of a group of heralds from the College of Heralds, who, during the 16th and 17th centuries, were dispatched across England to record in intricate detail the pedigrees of the great families of England. There is a fleeting reference in their Cheyne pedigrees to a William, son of John Cheyne of Chesham Bois (1466-1535) and a brief reference to this William’s marriage to an Emma Walwyn of Much Marcle. Fortunately, during their visits to Herefordshire, the heralds included a detailed history of the Walwyn family which led to the answers.

The trail begins around 1400. William Walwyn of Longford married Joan Whitney, daughter of the great soldier and landowner Sir Robert Whitney of Whitney-on-Wye. Around the same time Joan’s brother also called Robert Whitney married Wenllian Oldcastle of the influential Oldcastles of Almeley and niece of the famous Lollard rebel leader Sir John Oldcastle (1370-1417).

What bound these powerful Herefordshire families together – as it did with the Cheynes and other families in the Chiltern Hills – was their fanatical support for the heretical beliefs of John Wycliff and Lollardy and their protection of Lollard priests (5).

From the heralds’ work in Herefordshire, it emerges that Emma Walwyn of Much Marcle (c 1474 -?) married William Cheyne (1479 – 1512), eldest son of John Cheyne (1466 – 1535), Lord of the Manor of Chesham Bois.

As eldest son, William and his heirs would have been expected to inherit all his fathers’ lands and titles including that of Lord of the Manor of Chesham Bois. And so why, the question arises, apart from that mention on Jane’s memorial at Titchfield did William disappear into oblivion?

The explanation lies in those dates.

William married Emma Walwyn around 1500 and their daughter Jane Cheyne was born around 1505. William died aged around 34 in 1512 when Jane was just seven and (critically for our story) while his father was still alive.

William, who would have inherited everything, inherited nothing. He would have been living at his father’s home with his young family at the medieval family mansion which was being developed and enlarged at the heart of Chesham Bois manor (6) as the family wealth grew. But he would have been living there as son, not Lord of the Manor.

With William already dead, when his father John Cheyne died in 1535 it was the second son Robert Cheyne (1488-1552) who inherited the land and titles. And it was through Robert’s line that the Cheynes of Chesham Bois steadily prospered during the Tudor and Stuart period (7).

Charles Cheyne (1626-1698) was the Great Great Grandson of that Robert Cheyne. He married Lady Jane Cavendish, a noted playwright and poet, the granddaughter of Bess of Hardwick, and in 1681 was created 1st Viscount Newhaven by King Charles II as a reward for his loyalty. He bought the manor of Chelsea (remembered in Cheyne Walk, etc.) with his wife’s money.

Thomas Wriothesley, “Rising Star” of the Tudor Court

William’s death before his father without any inheritance raises the question of how his daughter Jane was deemed a suitable match for the rising star Thomas Wriothesley (1505-1550). While serving Thomas Cromwell, Thomas was created Clerk to the Signet at the court of King Henry VIII and he became known as one of Henry’s most loyal and ruthless enforcers.

Again, the clue to this marriage lies in the dates and in the great circle of influence among the families at Court.

It is unlikely that, without prospects, Jane’s marriage to Thomas Wriothesley would have been pre-arranged as a great dynastic match. Both were aged around 25 and dynastic marriages were often fixed when the betrothed pair were in their early teens. At the time of his marriage in 1530 Thomas was still employed in a middle ranking Court role, however it is that job which gives us the clue to the marriage.

Thomas Wriothesley had been working as secretary to Sir Edmund Peckham of Denham (1495 – 1564) who rose through a series of financial posts in the Royal Household to in 1544 be made High Treasurer of all the mints of England and Ireland by King Henry VIII. Crucially for our story, in 1516 Sir Edmund Peckham had married Anne Cheyne of Chesham Bois, younger sister of William and Robert. It is quite possible that it was through this network of relationships that the talented and ambitious Thomas became betrothed to his employer’s spirited young niece Jane Cheyne (8).

The Catholic Link

There was another powerful bond linking Jane Cheyne, Thomas Wriothesley, Sir Edmund Peckham and his wife, Jane’s Aunt Anne Cheyne: they were all Catholics.

It has been recorded that Jane as Countess of Southampton raised her children secretly as Catholics (9). Jane’s private prayer book held at the Bodleian Library carries has a warm inscription to her from the Catholic Queen Mary (Bloody Mary, at that time Princess Mary) (10)

This commitment to Catholicism – which put their lives at risk – seems deeply ironic given the Cheynes’ generations of support for heretical Lollardy which challenged the power of the Roman Catholic church and itself had threatened those lives.

However, it was not unusual for members of the same family to have different religious beliefs. It is said m land-grabbing robber barons embraced Lollardy mainly because it challenged the right of clerics to hold vast swathes of land. They sensed rich pickings if that right could be removed. And this is exactly what happened when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and re-distributed ecclesiastical lands among his courtiers.

The Cheynes of Drayton Beauchamp and Chesham Bois married into the great Herefordshire Lollard families of Oldcastle, Whitney and Walwyn whom they had come to know through service as Knights in the Royal Household of Richard II. The Cheynes gave open support to Sir John Oldcastle’s violent Lollard uprising against King Henry V in London at in 1414 after which both Roger Cheyne and his son Thomas were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower (Roger contracting an illness in the Tower which killed him).

It is probable that it was this Lollard bond between families sharing joint service at the Royal Court which may have sat behind the, apparently, unusual alliance between William Cheyne of rural Buckinghamshire and Emma Walwyn of distant Herefordshire.

Being a Catholic in itself, however, did not necessarily prove fatal. Protestant monarchs were most concerned by Catholics who stirred up rebellion against the Crown (or may have been used as figureheads for rebellion) which threatened that which has always mattered most to monarchs: their hold on power.

All of which brings us back, finally, to William Cheyne and William Shakespeare.

William’s daughter Jane was the Catholic matriarch of a powerful noble Catholic family, so well respected by the Protestant Queen Elizabeth that in 1569 the Queen stayed with the Countess of Southampton at Titchfield during a Royal Progress (11).

William Shakespeare was the product of a predominantly Catholic network of families in rural Warwickshire who (while his own religious views remain the subject of debate) became close friends with the Catholic Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, grandson of Jane Cheyne of Chesham Bois.

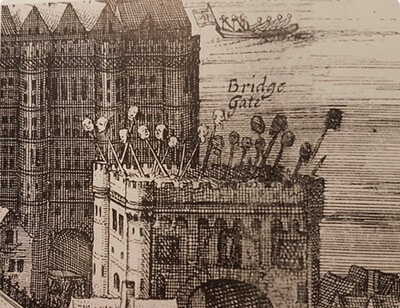

Arriving in London around 1585, Shakespeare would have been left in no doubt about the bloody fall-out from England’s violent religious turmoil. Crossing London Bridge, he would have seen, still impaled on a spike on top of Traitors Gate, the shrunken severed head of his mother’s cousin Edward Arden of Warwickshire – implicated in a Catholic plot against the Queen, arrested, convicted on flimsy evidence, executed, and beheaded.

Notes:

- Sir John Oldcastle led the Oldcastle Uprising of 1414 against King Henry V. The two men were close friends (Sir John appears as the king’s companion Sir John Falstaff in a number of Shakespeare’s plays). The King offered to pardon Sir John if he rejected his support of Lollards but he refused. There is a vivid image of Sir John being burned at the stake in 1417 in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs first published in 1563.

- The close relationship between William Shakespeare and his patron The 3rd Earl of Southampton is explored in Kenneth Brannagh’s 2018 film, All is True

- The tradition goes that during the 15th Century the Rithsley family, minor civil servants in Yorkshire, gradually lengthened their name to appear more noble and well-connected.

- See Anne Paton’s two articles about Chesham Bois Manor and the Cheynes of Chesham Bois:

Chesham Bois Manor, Home to the Cheyne Family for 350 Years, Records of Buckinghamshire, Volume 50, 2010

The Manor of Chesham Bois: - For example, Thomas Cheyne of Drayton Beauchamp (1394-1468) who was arrested following the 1414 Oldcastle Uprising was well-known for his protection and sponsorship of the Lollard priest Thomas Drayton.

- The original medieval mansion with well laid-out grounds features in an Estate Map of Chesham Bois Manor prepared for the Earl of Bedford around 1735 and held in the Russell Papers at Bedfordshire County Archives. The map provides a clear idea of the mansion’s haphazard, sprawling development.

- There is a detailed description of the evolution of the Chesham Bois branch of the Cheyne family from around 1200 in Anne Paton’s Articles (see above). The earlier history of the Cheyne family from Ralf de Chesnai arriving in England with William of Normandy in 1066, then spreading across Britain, is set out in R. W. L. Chesney’s typescript Le Fief de Quesneto (1962) held at the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Ref: MS. Top. gen. c. 76)

- The recorded evidence, as well as her memorial, paints a powerful picture of Jane Cheyne as the well-educated, highly sophisticated moving force in the Southampton family household after her husband’s death in 1550. She left a number of annotated books including an early edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, as well as her private prayer book, suggesting she was literate and well-read – and she was clearly confident enough to entertain her Queen in 1569.

- See G. P. V. Askrigg: Shakespeare and The Earl of Southampton (1968), pps 6-7

- Jane Wriothesley Private Prayer Book with inscriptions by Katherine Parr, Princess Mary etc. Bodleian Library, Oxford: ref: MS. Laud Misc. 1

- For a detailed list of Queen Elizabeth’s Summer Progresses, see Mary Hill Cole: The Portable Queen: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Ceremony (1999)