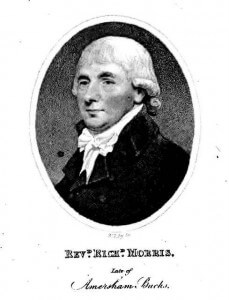

Richard Morris, Pastor of Amersham Baptist Church for 41 years from 1776

This account was written by Judy Buckley, one of whose ancestors, John Cocks, was the second pastor of the Upper Meeting after the separation of Amersham’s two Baptist congregations in 1823.

Memoirs of Richard Morris were compiled in 1819 by 24 year old Benjamin Godwin, Baptist Minister at Great Missenden from c.1813-1822. He began:- It had long been the wish of many who knew Mr Morris to possess an account of his early life; their requests, however, were unavailing till he was nearly in a dying state, when he dictated at intervals and a friend wrote. The resulting 90 pages mix a few basic facts with lengthy comments about Morris’s piety, from which some highlights are presented here with additional information.

Lancashire Origins 1747-67

Richard Morris’s own dictation began:-

I was born in the parish of Radcliffe in Lancashire 29th May 1747. My father George Morris was a respectable farmer. I was brought up to attend with my parents the Presbyterian Meeting at Cockney Moor; Dr Barnes was then Minister.

Radcliffe is about 7 miles north west of Manchester. The family farm may have been Lower Hagside, on Eton Hill near the river Irwell, where, in 1841, a William Morris aged 45 (perhaps Richard’s nephew) was farming. The Cockney Moor chapel at Ainsworth was founded in 1647 and still stands, about three miles (an hour’s walk) north-west of Radcliffe. Dr Thomas Barnes was minister there from 1768 (when Richard was 21) until 1779. Richard’s account continued:-

There was nothing remarkable about my early life, except that being the youngest child, and at a distance from any school, my education was, for several years, neglected. At this time I had strong convictions respecting Death, Eternity and Judgement to come, which obliged me to conclude that at some future time I would amend my life; and this was all I then knew about religion. But I found that instead of an alteration for the better, my heart and ways became more and more depraved.

When I was sixteen years old [in 1763] I was much distressed at the loss of a sister who died at the age of 20. And I resolved again to set out in religion with greater earnestness; but I was at this time unacquainted with the disease of sin and the remedy which God has provided in the Gospel; so that I found the resolutions melt away before the force of temptation.

About the year 1767 [he was 20] I was invited to visit a friend at West Chester, from which place I went with him through North Wales and returned through Liverpool to my relatives at Radcliffe. From this time I began to be very unsettled, partly [because] my father seemed to intend to give up the farm to a sister’s husband, and partly because the journey in Wales had given me a strong taste for travel. Knowing that I could not support the expense that must attend travelling, I came to a determination to enter the army, that I might have an opportunity of gratifying my inclination for seeing more of the world … [and] … adopted the resolution of entering the Oxford Blues.

Army Service 1767-73

After 1763, when the Treaty of Paris had ended the very expensive Seven Years War between England and France, the size of the army had been drastically reduced, but the Oxford Blues were still recruiting. Richard enlisted in Manchester in 1769 with a friend and, tall, well proportioned, six feet two inches, very striking in his regimentals, joined the regiment at Stamford in Lincolnshire. The horses belonged to the regiment, but the King’s shilling paid to a soldier upon enlistment (for life), the equivalent of one day’s pay, was to buy some of his initial equipment.

But the Blues did not travel abroad. They were merely quartered in various Midland towns, used as militia for policing duties, ready for action but mostly kicking their heels, without even a detachment in London to perform escort duties for the King. They were billeted out in lodgings, morale was low, discipline was slack, and Richard found that the riot and dissipation around him didn’t make him happy; He tried to reform but fell into the snare of intoxication. Resolutions of abstemiousness, fasting, and attending chapels to hear sermons were hampered by the scorn of his rougher fellow troopers. The officers labelled him Methodistical. At Loughborough, while the Commanding Officer was absent, the men subjected him to a traditional Cold Burning for the alleged crime of scandalising the regiment. He was tied up in the yard while they poured pails of iced water over him. Afterwards some men boasted, and some were ashamed, but he kept his head and calmly told them that he wouldn’t have been so good if they hadn’t washed away his sins.

In spite of opposition Richard continued to attend meetings whenever possible but was unsure which denomination to follow. Finally he arrived in Hemel Hempstead and, then in his mid twenties, he was taken under the wing of Baptist Pastor Mr [Morgan] Jones whose behaviour to me was in every respect that of a father … believing that God had designed me for the ministry, [he] spared no pains to instruct me in what he thought would be useful to me in future life.

Soldiers at that time were (by Articles of War) expected to attend the Established Church, and he hadn’t stopped being an Anglican Communicant, but he staunchly claimed that the Toleration Act of 1689 entitled him to hear sermons in his time off anywhere he chose. Desertion was unthinkable.

A compromise between his army duties and his determination to hear good preaching and learn to preach had to be reached. In 1772 Mr Jones drew up a petition to Lord Barrington at the War Office, requesting that Richard and a few friends of like mind who attended the Established Church on Sunday mornings, might be freed from barrack duties in the afternoon to exercise their right to attend dissenting meetings. This finally bore fruit, but when his officers discovered that Richard was beginning to preach himself, they took stronger action against him. Finally his case was reported to Lord Robert Manners, who took an interest, and his influence led to a formal Court Martial and honourable discharge.

As soon as I was discharged I went to London to thank Lord and Lady Manners. In the conversation which followed, her Ladyship enquired if I intended to go into the ministry. I replied that there were several things in the service of the Church of England to which I could not conscientiously conform. Upon which she cautioned him that he might find difficulties among the Dissenters also. But in 1773 Richard was invited to supply the Particular Baptists at Woodrow, succeeding their pastor, Mr Harris, who was both old and unwell, so he arranged for part-time tuition from Mr Clark of Chesham Bois, and almost certainly found employment assisting in the Hobbs family brush making business, a wise choice at the age of 26. And soon after his return from London, Mr. M. availed himself for some time of the instructions of Mr. Clark of Chesham Bois, a pious and learned clergy man of the Establishment, who kept an academy and prepared students for the university and for ordination.

Amersham Baptist Deacon Henry Hobbs, a Wood Turner and Brush Maker, had died in 1770 leaving a widow, Catherine (perhaps his second wife) and two daughters aged 22 and 12. Catherine, like many widows in those days, seems to have been carrying on her husband’s business after he died, probably offered Richard the job that started him off. Mary, the elder Hobbs daughter, was married to Amersham Carpenter William Woodbridge (with four children by 1770) and Martha (aged 15 when she met Richard) lived with her mother.

Amersham Pastor 1775-1818

On 15th June 1775 Richard married 17 year old Martha Hobbs. As she was under age, they needed a licence and the consent of her mother Catherine and the Trustee for her father’s estate who was Caleb Cock, the Baptist Minister at Chesham. Richard and Martha started married life with income from the family business. Later Richard took part in several other business ventures in the town, including setting up a cotton mill to provide employment. . One of the houses in Chapel Yard was inherited from his father-in-law and in 1816 he was still occupying a house in the High Street (possibly now No.125) described as formerly Henry Hobbs.

Almost a year after his marriage Richard was ordained at Woodrow 4th June 1776 aged 29. And for the rest of his life (after learning the hard way that Lady Manners has been right about the narrow-mindedness of Non-conformists) he embraced an open style of worship, in spite of some intolerant members who expected me to adopt the whole of their creed without hesitation, before they could cordially give me the right hand of friendship.

Soon he was giving an evening lecture in his own home in Amersham, and by 1777 he had fitted up a workshop his yard (later Chapel Yard) for meetings. In 1783 about ten people from Woodrow and Chesham split away from their own churches to meet at Amersham, and by October 1784 they had raised £256 and built a new meeting house.

Richard and Martha had five children; Mary (1776-1853) Richard (1788-1855) Elizabeth (1792-1837) Sophia (1793-1849) and George Washington (1795-1867). The children’s births were registered in the Lower Meeting chapel book among the families of other Amersham Baptists; their close friends William and Mary Potter, and Dorrells, Haileys, Holdens, Mortens, Shrimptons and Woodbridges.

In 1792 Richard accepted an invitation to take upon me the pastoral care of the church at Amersham, to which that of Woodrow was now united. In 1799 a larger meeting house seating 700 was built for £727.

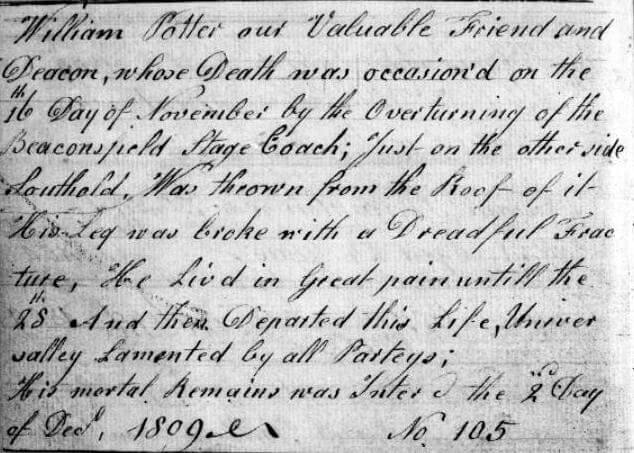

On the 25th of November, 1809, the loss of Richard’s great friend and deacon, Chair Maker William Potter, affected him deeply.

In 1811 another blow struck Richard aged 64, when Martha died, at only 53. Their elder son, Richard junior, would have started his apprenticeship to a Draper in London in about 1802, and he worked in Cheapside even after he went bankrupt in 1832, retiring to Chapel Yard by 1851. Sophia also went to London, but Mary, Elizabeth, and George (who worked for his father) were still at home to look after him until Mary married in 1812. On 17 Aug 1816 he made his will. First I give to my eldest daughter Mary the wife of John Hewet my freehold cottage … in the Franchise of Amersham now in the occupation of the said John Hewett … and afterwards to my grandson Richard Hewett an infant of the age of three years or thereabouts, the child of the said John and Mary.

The house wherein I now dwell and my three freehold cottages adjoining and their several gardens in or near the High Street in Amersham on the south side all other real estate to go to Richard Morris my eldest son subject to the payment of £100 to each of my three younger children George Washington Morris, Elizabeth Morris and Sophia Morris to be paid within 12 months.

He concluded by leaving £10 to his friend, Amersham Baker William Rouse and some investments and the residue to his three younger children, appointing Richard and William Toms [another Amersham Baker] as executors. His three closest friends were all named William; I wonder how he distinguished between them!

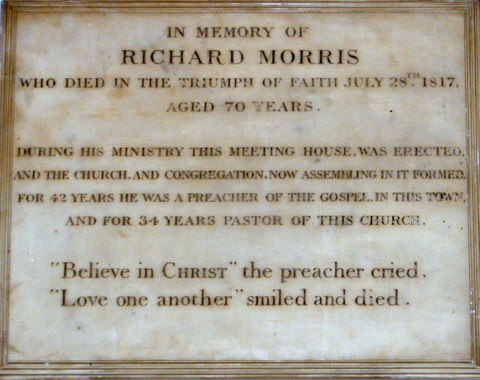

From April 1817 he was so weak that he organised help from younger ministers. To a young friend he said How far I have been useful in the world, another day must prove; but of one thing I am certain, that my aim and desire have been to do good to mankind. He managed to administer communion to his congregation on 1st June and preach for 20 minutes on 11th July, but after that he was failing fast, and he died on 28th July aged 70.

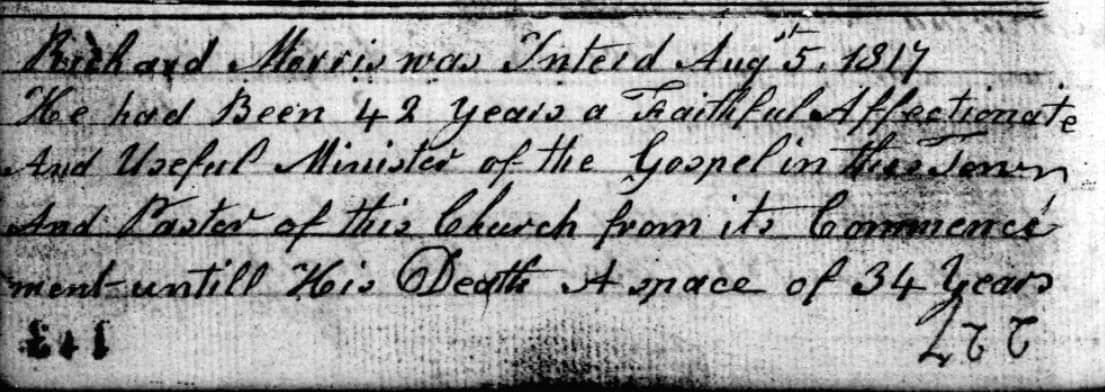

On 5th August 1817 his funeral sermon was preached to a large audience by Mr. Sexton, Baptist Minister at Chesham, with whom Mr. M. had lived in uninterrupted friendship for nearly thirty years. He was buried in a vault in the burial ground behind the chapel – close to the graves of his beloved wife and good friend William Potter.

Mary was the only one of Richard’s children who married in his lifetime, but not until a year after her mother had died. Quite a long time after their father’s death Sophia (in 1826 aged 33) and George (in 1841 aged 46) also married, but the next generation only numbered two. They had such extremely different, but interesting, lives that they need a story each. They will be added to this website soon. The story of Martha Morris, Richard’s granddaughter, is now on this site.