By Peter Borrows

On the north side of St Mary’s Church, Amersham, adjacent to the West Door, is a cluster of graves, the Weller family plot (see Fig. 1). There are also some memorials to the family inside the church. One records the death of Henry Weller in Black River, Jamaica, in 1815. Black River was a slave port in the parish of St Elizabeth, so, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, and with plenty of lockdown time available, I was prompted to investigate. Using only the University College London Legacies of British Slave Ownership[1] website and the usual on-line resources available to family genealogists – the census, church records, wills and newspapers in the UK and Jamaica – I have uncovered some perhaps surprising facts about the Weller family. To a modern eye, the subtlety of the various racial distinctions used in the Jamaica baptism records[2] may seem both astonishing and shocking.

The Weller brewing dynasty in Amersham was founded by William Weller (1727-1802), a maltster, and his wife Ann House (1732-1817) from High Wycombe. They had (at least) 8 children between 1760 and 1773, all born in High Wycombe and 2 more born in Amersham. The first, third and fourth sons, John Weller (1760-1843), William Weller (1763-1843) and Joseph Weller (1766-1857) became brewers in Amersham with their father, although Joseph suffered from ill health and was advised to move to the coast, so he left the brewery and moved to Folkestone in 1806 or 1807, and then emigrated to New South Wales in 1830. Unexpectedly, much of our information about the Weller family[3] comes from the descendants of the second son, Thomas Weller (1761-1823) who was not a brewer but moved to Penn as a butcher.

Of the brewing sons of William Weller, the eldest, John Weller (1760-1843), had (at least) 5 children by Katherine Fowler (1761-99) and Elizabeth Hickman (1769-1851). His first son Edward Weller (1790-1850) also became a brewer, the second, John Weller (1794-1862) became a clergyman and the third, Richard Weller (1798-1854), was living on an annuity by the time of the 1851 census. All very British, very conventional, although John was an embittered and not very conventional clergyman as he was buried in a neighbouring parish, not in his own, and his epitaph, composed by himself and inscribed in Latin (presumably so the villagers would not understand it) translates as:

Here lies John Weller S.T.P., at one time a fellow of Emmanuel College in Cambridge, from where, having left under a bad omen, he was appointed rector of the church of North Luffenham – truly a hard and thankless office, which at the least having caused him to feel utter disgust in the greatest part, he preferred his bones to be laid to rest in this alien ground.

The Jamaica Connection

Click on this link to view the Jamaican Weller family tree.

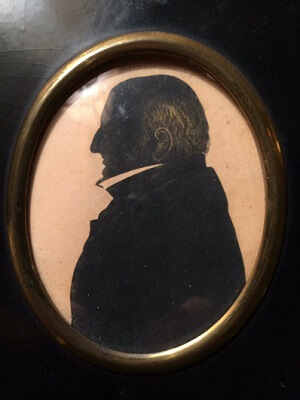

William Weller’s 3rd son, also William Weller (1763-1843), see Fig. 2, is more interesting. With Sarah Lacey (1762-1820) he had (at least) 8 children. Their fifth son, another William Weller (1797-1859) (and his descendants), followed his father and grandfather into the brewery. Their eldest son, Henry Weller (1788-1815), died in Black River, Jamaica and their second son, John Lacey Weller (1790-1823), was also carrying out business in Jamaica at that time. Their eldest daughter, Mary Weller (1783-1860), married George Channer (1779-1830), also of Black River, Jamaica, by licence in Amersham in July 1807, although he already had a family in Jamaica. Mary and George had (at least) 9 children, 3 of whom died in infancy and these 3 are recorded on a tablet in St Mary’s Church. Their eldest daughter Mary Elizabeth Channer was baptised in Amersham in July 1808. It’s unclear where and when Frederick Lacey Channer was born but he died aged 3 months. However, their 7 other children from 1811 onwards were baptised in Heston in Middlesex.

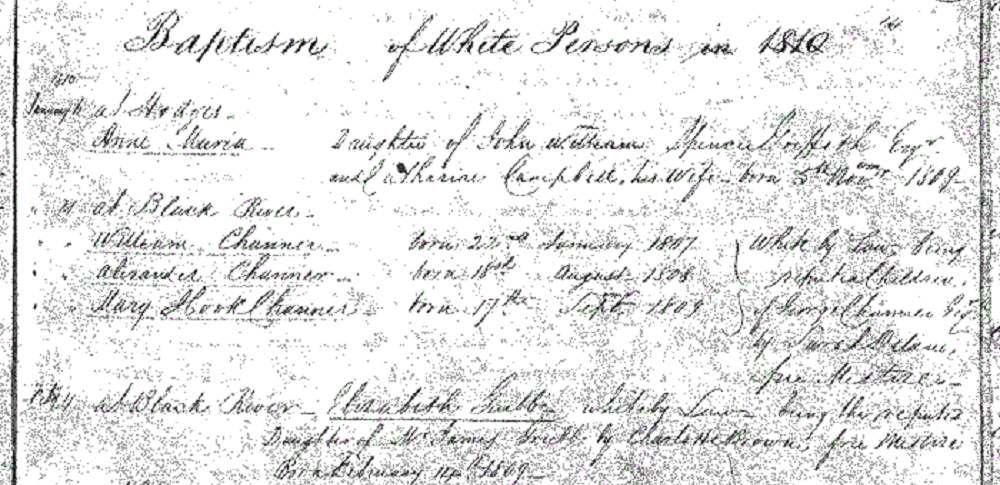

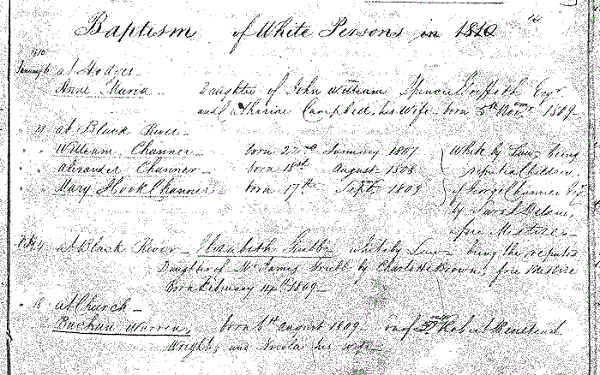

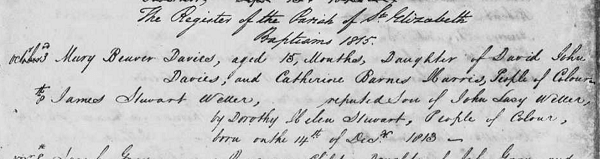

Despite his marriage in Amersham in 1807, George Channer continued to have business in Jamaica. According to Legacies of British Slave Ownership, in 1808 he filed accounts for the Bath Estate in St Elizabeth. This was a coffee plantation owned by the heirs of the recently deceased John Jenkins. Presumably he was a manager or book-keeper working for slave owners rather than a slave owner himself. In 1809, at the height of the Napoleonic wars, George was a Major in the St Elizabeth Militia, and in January took part in the invasion of the French colony of Martinique. George Channer’s second family in Jamaica comprised 4 children born in 1804, 1807, 1808 and 1809 to Sarah Delano. The three younger children were baptised as ‘white by law’ in 1810 (see Fig. 3); the eldest, James, was just reported as ‘white’. Sarah is described on the Baptism registers as a Mestize. Although this was the term used in Hispanic America for children of European and indigenous parents, by this time in Jamaica ‘mestees’ was used to describe those who were only 1/8 black (octaroons). Under an Act of 1761, a white man who fathered non-white children could have a Private Act presented to the Jamaican National Assembly. This Act would give them the same rights and privileges as British subjects, born of white parents, subject to certain restrictions, usually with respect to voting. However, the Act seems not to have been invoked after about 1802 and ‘white by law’ by then simply means more than ¾ white. ‘Reputed’ does not mean that paternity was disputed, just that the couple were not married. According to John Stewart, a not entirely disinterested white male writing in 1823, it was regarded as degrading for a white man to marry a coloured woman but quite normal to have her as a mistress or ‘housekeeper’ and he said such women considered it more genteel and reputable to hold such a position than to marry a coloured man[4] . In fact, Sarah Delano was quite a wealthy woman. In 1836 she was awarded £286-12s-8d by the British Government when her 11 slaves were freed.

In 2021, the Museum was contacted by Angela Macfarlane, a descendant of George Channer and Sarah Delano. She told us Sarah was the daughter of Nathaniel Delano, a river pilot in St Elizabeth and later harbour master, and Rachel Pinto, who must have been a quadroon (1/4 black).

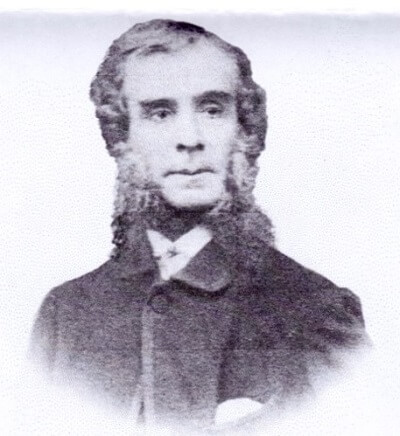

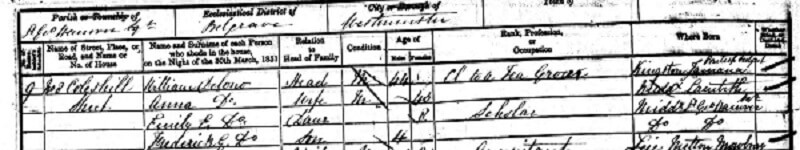

In the 1830s, a number of members of the Pinto family (from both Jamaica and Trinidad) were awarded compensation when their slaves were freed by the British Government. The Delano family is believed originally to have been of French descent, probably Huguenots. The second child of George and Sarah, William Delano (1807- 1866) (see Fig. 4), came to England in about 1830 and married Anne Howe in Lambeth in 1834. They lived in Pimlico and had five children while William worked as a clerk to a tea grocer. Interestingly, the 1851 census, although giving his birthplace as Jamaica, states clearly he is a British subject (see Fig. 5). Their second child was William Henry Delano (1838 – 1921). He was not listed with the rest of the family on the 1851 census because he was a pupil at Christ’s Hospital School in Newgate. He married Ada Rebecca Robinson and worked as a civil engineer in France. Their four children were all born in Paris. Interestingly, their eldest child, a son, was called Hugh Channer Delano and their fourth, a daughter, Maud Channer Delano, their middle names recalling their great-grandfather. It was from their eldest daughter, Hilda Dalrymple Delano (1880-1973), that the Museum’s contact was descended. Angela Macfarlane was Hilda’s granddaughter, George Channer’s great-great-great-granddaughter. Angela Macfarlane’s father had been baptised with the Channer Christian name.

For a few years, George Channer was a business partner of William Weller’s eldest son, Henry Weller but the partnership was dissolved in 1811[5] and Henry carried on the business on his own. George seems to have been a rather disreputable business man because he left Jamaica secretly in 1813[6]. Even after he left Jamaica, his financial affairs rumbled on and then William Weller’s 2nd son, John-Lacey Weller was appointed to wind up those affairs[7].

The three notices referred to above all appeared in the Royal Gazette of Jamaica and were signed by A. Girdwood, as the attorney. It is interesting to note that the eldest (legitimate) surviving son of Mary Weller (1783-1860) and George Channer (1779-1830) was baptised George Girdwood Channer in Heston, Middlesex in 1811, presumably in thanks to his attorney, Alexander Girdwood, in Jamaica. Alexander is listed in Legacies of British Slave Ownership in 1817 as Executor of the Pisgah Estate with 40 slaves, although he had died by 1818. A Frances Girdwood received £546-12s-2d compensation for 28 slaves. There were several slaves baptised with the name Frances Girdwood (and other first names), no parents listed, but the surname is unusual so it seems likely that Alexander was responsible.

Meanwhile, George Channer’s problems continued and in 1818 William Williams took over as Receiver from the late Alex Girdwood[8] and in 1820 George was made bankrupt in London[9]. Nothing daunted, he was then involved in setting up a marine insurance business in 1824[10] and continued in this until his death in Amersham in 1830[11].

George’s second surviving (legitimate) son, Alfred Taylor Channer seems to have been a rather prosperous clerk in, surprise, surprise, a marine insurance office, keeping 2 servants according to the 1851 census. George and Mary’s second daughter, Clara Ann Channer (1816-?) married Captain Robert Shortred in Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh in India in 1844, where he was serving in the 2nd Bombay European Regiment. It was presumably no coincidence that her brother, George Girdwood Channer (1811-?) was captain of ordnance in Allahabad at the same time.

Our contact, Angela Macfarlane, told us that a few years ago she had seen a medal on sale inscribed with George Channer’s name. As a member of the British force which invaded the French colony of Martinique in January/February 1809 he would have been eligible for the Military General Service Medal (MGSM) issued to officers and men of the British Army as a retrospective award for various military actions from 1793–1814, including the Napoleonic wars. However, only those living when it was issued in 1847 could make the retrospective claim, which clearly excluded George Channer who died in 1830. Apparently, it was not uncommon for relatives of deceased soldiers to purchase other people’s medals and re-engrave with their relative’s name. So, it seems that some of George Channer’s descendants were as deceitful as he had been. Or did his Amersham wife know about his mistress in Jamaica?

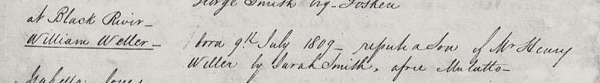

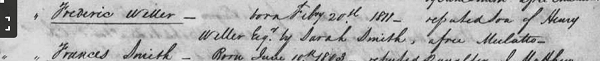

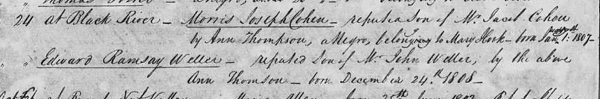

Now to return to the Weller brothers in Black River, Jamaica. Like George Channer, Henry Weller was not married but had a family with 2 children, William and Frederic by Sarah Smith, described as a free mulatto (see Figs. 6 and 7). A mulatto is the child of one black and one white parent. Henry died at Black River in 18153.

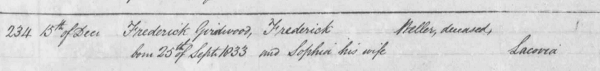

Henry’s son William became a planter. Frederic(k) died in 1833 and was deceased by the time his son Frederick Girdwood Weller was baptised. Note the Girdwood middle name, reflecting both the Channers and Alexander Girdwood, the Jamaican attorney. These families were intimately connected. Frederic(k)’s wife was Sophia.

In Legacies of British Slave Ownership, there is only one award of compensation to any Weller for freeing their slaves – to Sophia Weller. She had 3 slaves in St Elizabeth and was awarded £65-13s-11d. It is very likely, therefore, that Frederic(k) Weller, son of a free mulatto and an Amersham Weller, had been a slave owner.

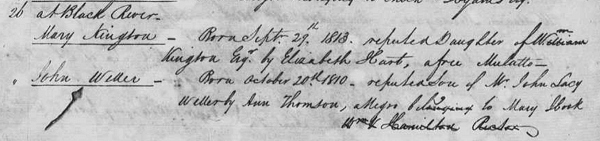

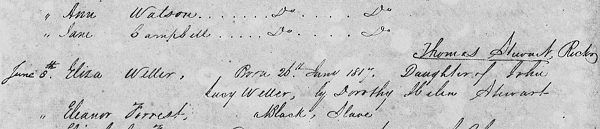

Henry’s brother, John-Lacey Weller, also had a family in Black River. His first children, Edward Ramsay Weller and John Weller, are by Ann Thomson, a negro, described as ‘belonging to Mary Hook’ (see Figs. 9 and 10). He then had 2 more children, James Stewart Weller and Eliza Weller, with Dorothy Helen Stewart (see Figs. 11 and 12), who was described as ‘people (sic!) of colour’ on James’s baptism. James became an accountant.

It seems that in the early part of the 19th century, some members of the Weller family had extensive affairs, both financial and of the heart, in Jamaica and benefitted indirectly from the slave trade and their mixed-race descendants probably owned slaves.

Read about Amersham’s support for the anti-slavery movement by clicking on this link.

The connection to Australia and New Zealand

Click on this link to view the family tree.

As mentioned above, Joseph Weller (1766-1857) was one of the sons of William Weller (1728-1802), founder of the brewing dynasty, and Joseph, like his brothers John and William, initially became a brewer. However, he suffered from consumption (tuberculosis) and was advised to move to a warmer, coastal climate. Joseph married Mary Brooks (daughter of a maltster) in Aylesbury in 1801 and his first 2 sons, Joseph Brooks Weller and George Weller were baptised in Amersham but by 1807 when his first (surviving) daughter, Mary Brooks Weller, was baptised, he was living in Folkestone. His brothers, John Weller (1760-1843) and William Weller (1763-1843) must have bought out his share of the brewery for a considerable sum and he invested that in a sizeable estate near Folkestone in Kent[12]. He later had another daughter, Ann Meek, and his youngest son, Edward, there.

However, Joseph’s ill health continued and he was advised to go on a long sea voyage. His two elder sons, Joseph Brooks and George, made separate reconnaissance trips to Australia in the 1820s and after returning to England seem to have persuaded the whole family to emigrate there. Joseph Brooks and Edward went first in 1829 and were followed in 1830 by brother George, with his new wife Eliza Barwise, his father and his wife and George’s 2 surviving sisters. Joseph had sold his estates near Folkestone for a large sum of money. One source said he had sold property in Folkestone to the Earl of Radnor (Viscount Folkestone) for ‘a six-figure sum’[13] and another that he took his money to Australia in sacks containing 12,000 sovereigns. Since 1817, a gold sovereign has weighed 7.988 g so the sacks would have been just under 100 kg and in 2017 the money would be worth a little over £800,000. Sources quoting a value of £80,000 were probably calculating a figure based on values in the 1970s10, 11. On arrival in New South Wales, part of the money was invested in land but part in setting up a shipping and whaling business (see Fig. 13) in Sydney which became very successful. A year later, in 1831, the younger sons Joseph Brooks and Edward set off in their whaler the Lucy Ann for New Zealand to set up a whaling business near what later developed into the city of Dunedin10. They landed at what became known as Weller’s Rock (although the Maoris already had a name for it). Quickly, they became very successful, employing over 80 people, not just there but in 6 other whaling stations, and in farming and selling supplies to visiting ships.

Edward had one daughter with each of two Maori women, although both women died soon after giving birth. The elder daughter, Fanny Hana (1835-1907), had four children by a Maori man but the younger daughter, Nani (1840-1924) had 12 children with Daniel Raniera Ellison11 (1839-1920), himself the son of a Maori woman and an English whaler. Some of Nani and Daniel’s children made distinguished contributions to New Zealand society. The 4th child, Tom Rangiwahia Ellison (1867-1904) was an international rugby player, touring Australia and Great Britain in 1888/9. His younger brother, Edward Pohau Ellison (1884-1963), played both rugby and cricket for Otago University where he graduated MB, ChB in 1919, returning in 1925 to undertake postgraduate studies in tropical medicine. Having worked in Samoa, Fiji and the Cook Islands, as well as New Zealand, he was awarded an OBE in 1938 for services to the Polynesian people. The Weller family’s generally good relationships with the Maoris, and the positive contributions of their descendants, are seen as part of the reason for the better relationship between Europeans and indigenous peoples in New Zealand than in Australia.

Joseph Brooks and Edward ran the Otago whaling station successfully for some years. When Joseph died of tuberculosis in 1835, Edward had him shipped back to Sydney in a barrel of rum. Edward had a reputation for being rather stubborn and insisted on captaining some of the whaling expeditions, much to the concern of (married) brother George running the Australian branch of the business in Sydney. The whaling business declined somewhat in the late 1830s and George was keen to pull out but it was only after some rather dodgy land deals that Edward left New Zealand, handing over the remaining business to Charles Schultze, who later married Edward’s sister Anne Meek Weller (1817-1887).

Towards the end of 2020 sea shanties became very popular on the social medium TikTok and in particular one sea shanty called The Wellerman[14]. It tells the story of whalers waiting for the supply ship, The Wellerman, i.e., one of the ships run by the Weller supply company of Sydney, to bring them sugar, tea and rum. It also tells of the obstinate captain who, having harpooned a whale, won’t cut the line despite the whale towing the boat for days on end. Surely that captain must be based on the rather obstinate Edward Weller? And, of course, the so eagerly-awaited sugar and rum might have been supplied by the Weller cousins in Jamaica.

The Wellerman

There once was a ship that put to sea,

And the name of that ship was the Billy o’ Tea

The winds blew hard, her bow dipped down,

Blow, me bully boys, blow!

Chorus (after each verse):

(HUH!)

Soon may the Wellerman come

to bring us sugar and tea and rum.

One day, when the tonguing’ is done,

We’ll take our leave and go.

She had not been two weeks from shore

When down on her a right whale bore.

The captain called all hands and swore

He’d take that whale in tow.

{Chorus}

Before the boat had hit the water

The whale’s tail came up and caught her.

All hands to the side, harpooned and fought her,

When she dived down below.

{Chorus}

No line was cut, no whale was freed,

An’ the captain’s mind was not on greed!

But he belonged to the Whaleman’s creed

She took that ship in tow.

{Chorus}

For forty days or even more,

the line went slack then tight once more,

All boats were lost, there were only four

and still that whale did go.

{Chorus}

As far as I’ve heard, the fight’s still on,

The line’s not cut, and the whale’s not gone!

The Wellerman makes his regular call

to encourage the captain, crew and all!

{Chorus x2 til Finish}

Interestingly, in 1842 the American Hermann Melville joined the whaler Lucy Anne (the same vessel on which the Weller brothers had sailed from Australia to New Zealand) on the Marquesas Islands, whence he sailed to Tahiti. Melville was the author of Moby-Dick. Was Edward not only the inspiration for The Wellerman captain but also the inspiration for Captain Ahab?

References

[1]University College London, Legacies of British Slave-ownership,[2]https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1827268

[3]http://weller.org.uk/cgi-bin/FamilyTree/ShowFamily.pl?PersonID=116

[4]Stewart, J., A view of the past and present state of the island of Jamaica …, (1823), Edinburgh & London: Oliver & Boyd, G & W B Whittaker.

[5]Royal Gazette of Jamaica, 25 September 1811.

[6]Royal Gazette of Jamaica, 3 August 1813.

[7]Royal Gazette of Jamaica, 21 October 1815.

[8]Royal Gazette of Jamaica, 28 July 1818.

[9]The Star (London), 21 August 1820.

[10]Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 1 August 1824.

[11]George Channer’s grave is the 2nd from the left, in the front row, in the photograph at the start of this article, Fig.1.

[12]https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1w13/weller-edward.

[13]http://tomswhakapapa.co.nz/brons_family_history_017.htm.

[14]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qP-7GNoDJ5c