The ministry of John Cocks (1783-1850) at the Upper Meeting in Amersham 1842-1850

This account, written by his grandson’s great granddaughter, Judy Buckley, is a short biography of the second pastor of the Upper Meeting after the separation of Amersham’s two Baptist congregations in 1823. (Any questions to the author can be sent via the contact page.)

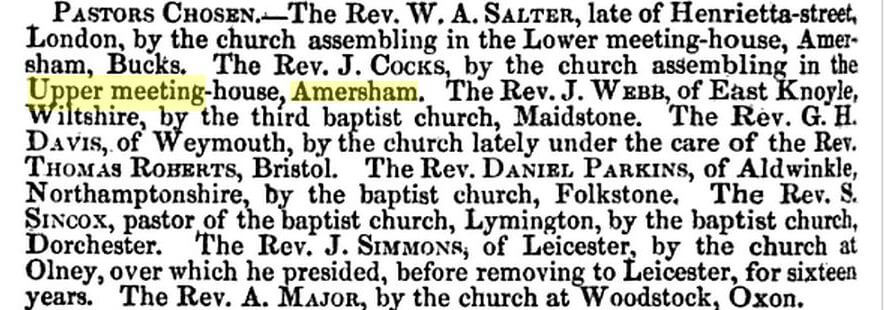

Seeking a new pastor for the Amersham Upper Meeting

In the early nineteenth century the Baptist Movement divided. Closed communion chapels held preaching services for all comers, but followed the commandment of St Paul to the Corinthians by restricting the serving of the elements of Holy Communion to their own members, who were of known good standing. But now I have written unto you not to keep company, if any man that is called a brother be a fornicator, or covetous, or an idolator, or a railer, or a drunkard, or an extortioner; with such an one no not to eat. 1 Corinthians 5:9-11

The split came in Amersham in 1823, when the Lower Meeting remained open communion as it had been since it was started in the 1780s by Richard Morris (1747-1817) but the old Upper Meeting became a closed communion chapel.

James Cooper (1794 – 1871) came to Amersham, his first pastorship, in 1819 and stayed for 20 years (his daughter Angelina married Samuel Toovey) Four years after he arrived he led a small separating group away from the main Baptist congregation to the old Upper Meeting chapel. In 1839 when he moved to Leighton Buzzard, it took the Upper Meeting deacons over a year to find someone to replace him. As John Cocks wrote afterwards in the Baptist Reporter Their late beloved pastor, Mr. Cooper, having removed from them, they were left without pastor for a long time.

James Cooper’s roots had been in Bath, where he was a member of the closed congregation of Revd. John Paul Porter (1759-1832). That congregation also included Opie Smith (1751-1837) the wealthy philanthropic Bath brewer who was one of John Cock’s mentors. Opie knew John before 1822 when he made a significant contribution to the funds for the chapel John built in Crediton in Devon. And during the early 1830s, while recovering from a family tragedy, John stayed at Westfield, Opie’s home in Bath. When Opie Smith died in 1837 at the great age of 86, his nephew James Grant Smith inherited Westfield and his uncle’s influence in the Baptist movement, becoming among other things Treasurer of the Society for the Support of Aged and Infirm Ministers.

In 1839 James Cooper may have advised the Upper Meeting deacons to contact James Grant Smith in Bath, to find a new pastor with similar views to his own. John Cocks, whom Grant Smith knew well, was also a closed communion Baptist. In 1823 Cock’s name was included in a list in The Baptist Magazine of The Particular or Calvinistic Baptist Churches in England, introduced as follows:-

The “Confession of Faith” 1689 is the standard of doctrine which the Particular Baptists have always avowed. By the principles of this Confession we have endeavoured to regulate the following list, not admitting any church whose minister is known to be either Arminian [maintaining that although God gives indispensable help in salvation, ultimately only the free will of man can decide the issue] Antinomian [believing that Christians are released by grace from the obligation of observing the moral law] or Anti-Trinitarian [denying the existence of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost]. Some have pastors who are Paedobaptists [allowing infant baptism] but it is supposed the majority are Baptists [only baptising adults].

From which it may be gathered that John was a Baptist Minister who accepted the Trinity and the necessity of Divine help for Salvation, while insisting that his chapel members must also try to lead good, devout, and teetotal lives. Indeed, in 1843 and in 1849 he invited Dr Jabez Burns, a well-known preacher on teetotalism who lived in Paddington, to preach at the Upper Meeting.

And John had struggled in his previous settled pastorship at Twerton Chapel, near Bath, because he was too strict. Deacons had to balance the chapel books, Twerton was a new chapel in a poor area, and a minister who expelled members for drunkenness and immorality caused loss of revenue. He resigned from Twerton because of unpleasantness in 1834, but was still living and preaching in the Bath area, while looking for a new settled post.

But although John was strict, he was inspiring and energetic. His colleagues at the Home Missionary Society and the Western Association would have vouched for his record as a popular preacher, valued by his small congregations, who worked unstintingly for them, built several new chapels and ran successful Sunday schools. Here is the testimony written for him in 1821 when he was 38, by Rev Samuel Kilpin of Exeter, one of his mentors:-

I am happy to bear my testimony to the character and labours of Mr Cocks, your missionary at Crediton. He has carried the gospel into some of the most destitute villages in that neighbourhood; and several persons have been so convinced of sin, and inclined to seek the Saviour, that they now come from those villages a distance of three or four miles to attend his ministry on the Lord’s day. Mr C appears to be every way adapted to that station; he preaches sometimes four times on Lord’s day: and every evening in the week except Saturday, he either preaches or goes from house to house distributing religious tracts.

The new pastor, his family and his health

When John Cocks arrived in Amersham at the age of 59 (at which time of life a richer man might have been able to retire) he must have been grateful, after several much harder postings, for a peaceful position in charge of a small chapel in a comfortable friendly market town very like his birthplace in North Devon. And so he accepted, and several church magazines reported The Rev. John Cocks, late of Bath, has accepted the unanimous invitation of the church assembling in the Upper Meeting, Amersham, to become their pastor, and entered upon his labours, Jan. 2, 1842.

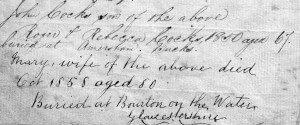

The only family member that John and his wife Mary brought to Amersham with them was their six year old orphaned granddaughter. Four of their own seven children had died. Baby John I died in infancy in 1817, Julia died aged 18 of diphtheria very soon after beginning her first job as a dressmaker in Bristol in 1830, John II drowned while bathing aged 13 in 1833, and Elijah, a Tailor (father of granddaughter Julia), died of consumption in Twerton in 1840. His widow Sarah worked for a bookseller in London, leaving little Julia with her grandparents. Well might John write, in 1847, It is true, we have had our trials in afflictions of body and distressing bereavements of dear Children, but, we have hope in their death, and trust that all things work together for good.

To lose lose four out of seven children in such tragic ways was bad enough, but John’s reference to afflictions of body were equally significant. According to his death certificate John suffered from diabetes for at least six months before he died, and there are indications that he may have had mild diabetes all his life, controlled by abstemious diet. Partly because he was not rich, and partly because he avoided alcohol. Before the discovery of insulin in the 1920s, diabetes was a well known but feared disease that caused blindness, loss of limbs, kidney failure, strokes, and heart attacks. 5% adults with diabetes died within two years, and fewer than 20% lived more than ten, because of complications from uncontrolled blood sugars. Since about 1800 doctors had known that excess blood sugar in people with diabetes could be controlled by low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets. The first indication of John’s health problems can be found in a letter from his mentor Revd. Samuel Kilpin of Exeter (who knew what he was talking about; he had earlier injured his own health by refusing to eat meat in order to save money for good causes) in a long letter about funding new chapels – when John was 38 in 1821:-

Don’t … refuse to drink a little Cyder when you are asked, but never drink it except the cold intake of let the heat of your body be the standard therefore never drink when you are very hot. Immediately after preaching Coffee, Tea or Warm Milk with a little sugar and nutmeg or allspice is good. I write this not to guard you against excess but to guard you from not taking enough. Our souls and bodies are to each other what a man and his horse is to each other on a journey. If you give him too much Corn he will kick up and throw you, if you don’t give him enough he will knock up and you must lead him home.

It sounds as Samuel knew that John avoided alcohol, and perhaps even that he had sometime collapsed from exhaustion. And nine years after that in 1830 when he was 47, a postscript to the very touching obituary to his daughter Julia, ran Her father had recently suffered the amputation of one of his legs. Maybe the result of diabetes, rather than an accident.

The remaining three of the seven Cocks children were, in 1842, not only surviving but flourishing. The eldest son, Japhia, a shoemaker like his father, had married and emigrated to Adelaide in 1838. His many descendants still flourish in Australia. Daughter Hephzibah, who married George Youatt, a London pianoforte maker, in 1839, founded the large Youatt clan in London and Manchester, which includes the author of this account. And youngest daughter Jemima, still a spinster when they came to Amersham, married very soon after her father’s death and provided a final home for her widowed mother in Gloucestershire. She left Wilkins descendants in Devizes.

His origins and experience

John Cocks’ father was a well established Stone Mason in Great Torrington. He held leases on several pieces of land in Torrington, but no record of the family business survive until John’s brother Walter (1775-1840) eight years older than John, had taken over and made it successful, rebuilding the church tower in 1828 and building the Torrington Pannier Market.

John was the youngest child. His father, Roger Cocks (1731-1802) and his mother, Rebecca Browne (1739-1791) were married in 1762 and had (according to John’s obituary written in 1851) thirteen children. Nine of them can be named, but by the time John was born only five were still alive. His eldest sister Rebecca, 20 years older than John, was married with a baby when John was born. She had three more children and died in a 1790.

His second sister Philippa married a mason and died in 1791, a few days before their mother, when John was eight. Walter, and another elder brother, James, were both masons, and another brother Roger was a scrivener. The family all attended the parish church, where Walter’s headstone, and his initials in cobbles by the south door can still be found. John didn’t join the family business, but his knowledge of the trade must have helped him to organise the building of two new baptist chapels and extend others. He became a shoemaker.

His second sister Philippa married a mason and died in 1791, a few days before their mother, when John was eight. Walter, and another elder brother, James, were both masons, and another brother Roger was a scrivener. The family all attended the parish church, where Walter’s headstone, and his initials in cobbles by the south door can still be found. John didn’t join the family business, but his knowledge of the trade must have helped him to organise the building of two new baptist chapels and extend others. He became a shoemaker.

Shoes were then all handmade. Depending on hours worked and help available from family, shoemakers might earn around £25 a year, which was no more than a common labourer. A subsistence wage, especially for a family with several small children. However, the capital outlay on tools was quite small and a shoemaker, working (and selling) from home in his own way, and at his own speed, could be very independent.

And since it was a highly skilled job, shoe making was a surprisingly well-respected trade. Many shoemakers, who of course must understand size and measurements and keep accounts, could read and write, taught their children at home and sent them to school. It was a good choice of trade for a man with an ambition to establish himself as a preacher, with the hope of a settled pastorship one day. In 1807 Thomas Roberts, the youngish Baptist Minister of Brixham (flourishing market town, sea-port, and extensive fishing station) was paid a salary of £60 a year, about double a shoemaker’s income.

His education and religious training

John’s mother was the daughter of Walter Browne, Master of the Torrington Bluecoat school, but she died in 1791 when he was eight. His obituary, written in 1851 states His mother died when he was very young, and he seems to have had little instruction or restraint. His father seems to have married again within a year, and perhaps the eight year old boy and his stepmother didn’t agree. He probably went to school until he was 14, and was then apprenticed to a shoemaker, either in Devon or London. His obituary continued After a dissipated youth, he left home for London.

His apprenticeship would normally have lasted from 1797-1804 so either the apprenticeship itself, or his first job as a journeyman was in London, where he became acquainted with some pious young men, by whom he was invited to hear Dr. Jenkins, at Orange Street Chapel, and under his ministry he was convinced of his sinful state, and of the need of salvation by Jesus Christ.

That dramatic change sent him back to North Devon. He no sooner felt the mercy and love of God for himself than he was desirous to tell that love to his brethren, and he returned home in order to commence preaching at his native place. He must then have earned his living as a shoemaker either in Torrington or in Bideford, and it was in Bideford that he met his future wife, Mary Heay, a childless widow, five years older than he was, who certainly had some income of her own. Mary was the daughter of a coastal mariner with a grocer’s shop. They were married in Bideford parish church in 1807 when John was 24 and Mary was 30. Mary was a great support to John, once described in a letter to him as your prudent wife

Itinerant preaching added to normal working hours was hard and daunting, because the Baptist cause in North Devon was very new. He met with much opposition, through which, however, he continued his labours without shrinking, and with some success. At this time, also, he became convinced of the propriety and obligation of believers’ baptism, and he was baptized in a river near the town. This would in fact have been John’s second baptism, as his parents christened him as a baby in Torrington Parish Church.

Lack of work and the wish for further education may be why, by 1811 John and Mary and their two small boys were living in London, where they joined the Wesleyan Chapel at Waterloo Street in Hammersmith. Two baby daughters were baptised there in 1811 and 1813. Much later, in 1843 John was to write, in an amused vein, that in Amersham his chapel had four deacons and was composed of baptised believers and infant sprinklers! He was an infant sprinkler himself. In London John was almost certainly working as a shoemaker, and perhaps attending evening classes or being tutored in Greek, Hebrew and bible study. Stepney Baptist Academy opened in 1810, and they certainly accepted evening students as well as a small number of full time trainees.

Settled pastorships before Amersham

By 1815 John and Mary were back in Devon, and in 1817 John, aged 34, was ordained minister of his first Baptist chapel in Calstock, recently formed as a branch of the Devonport Chapel. It was not a well paid position, and this letter shows how small incomes were for some Baptist ministers.

To Revd W Wilcocks, Pastor of the Baptist Church in Pembroke Street, Plymouth Dock, Devonshire

My dear Sir, Last Tuesday I got our Deacons to grant £3 out of our annual collection for poor Ministers for Mr Cocks of Calstock. I apply’d last year, but having mislaid his letter, my memory w’d not suffice to state his Case particularly and they objected that they knew nothing of him, not do I remember the name of the place at which he preached, I could only tell them that I remembered you and Mr Davis had recommended him. I since laid my hands on his letter, and read it to them, when they voted the above donation … Yours respectfully John Ryland

John Ryland was Principal of the Baptist Colleegin Bristol, and although he took little interest in John Cocks, two of his good friends became John’s mentors. One was Samuel Kilpin of Exeter and the other was the aforementioned Opie Smith of Bath. Both of them were influential in the Baptist Home Missionary Society, and soon they arranged for John to move to Crediton. By 1821 with the zealous and liberal aid of the Rev. S. Kilpin, of Exeter, and Opie Smith, Esq., of Bath, he was enabled to erect a chapel. And a letter from Samuel Kilpin giving John very detailed advice about raising funds to build the chapel in Crediton survives with the friendly comment My d[ea]r wife said it appears that no man sent Mr C to Crediton but God only.

While John was at Crediton he (presumably because he knew the young man’s family very well) visited 19 year-old Philip Chappell of Great Torrington at the Exeter Assizes when he was tried for the murder of his pregnant girlfriend, found battered and drowned in the river Torridge on 8th December 1821. The case was heard at Exeter Assizes on Friday 22nd March 1822

All the witnesses for the prosecution were called again, with several other persons to speak to the character of the prisoner, and all concurred in his general good conduct and gentle demeanour up the fatal occurrence. It was a melancholy sight to observe his father and mother brought forward to bear testimony against him. A respectable dissenting minister [John Cocks] gained admittance to the unhappy young man the same evening [Friday] and obtained from him a confession of his guilt – that while walking with her on the bank of the river, he stunned her by repeated blows on the head with a stick and then threw her into the water; but that the dreadful act was not premeditated.

Philip was sentenced that afternoon to be hanged on Monday 25th March, and immediately Exeter Minister Samuel Kilpin wrote to John Cocks to insist that he visit Philip again in the condemned cell. It was a three hour walk from Crediton to Exeter.

Dear Cocks, Providence appears to appoint out your duty to come in either this evening or tomorrow morning and spend a good part of the Sabbath with the poor condemned wretch. Your visit is mentioned in the Papers this morning very respectfully. Come over. Mr Sturgess shall come and preach for you. He cannot preach but twice and would wish to return in the Evening. He will be sure to be with you in time for meeting tomorrow Morning. Who can tell but God may give you this lost soul. Yours indeed S.K. (Revd. Mr Coxe Bap Minister Crediton To be delivered immediately as it is on business concerning the poor man that is to be executed on Monday)

On 1st January 1823. A new Baptist Meeting was opened at Crediton … the congregations were not large (there being much prejudice to be removed) but we hope the interesting services of the day will long be remembered by those who were present.

In 1826, John left Crediton and transferred his residence to Periton, near Minehead, at which latter place, also, he was enabled to erect a chapel, under the patronage of the [Home Missionary] Society.

Minehead chapel was built by the persevering efforts of the pious and worthy minister, and a few other friends, notwithstanding numerous … insurmountable obstacles … in no place could such exertions be more necessary or desirable… the moral aspect of the town is as dreary as its situation is delightful and romantic.

In November 1832 John’s chapel members at Minehead minuted;

We extremely regret that our beloved pastor Mr. John Cocks should be compelled to leave us and we believe the cause of his removal was the decided interest he took in the cause of civil and religious liberty, for this he was persecuted, both by the professors and open enemies of the cross of Christ and we bear testimony to his diligent, faithful and pious labours amongst us during 7 years and having been the instrument of erecting in Minehead a chapel and dwelling house for the minister.

John’s persecutors were Minehead landlord and MP John Fownes Luttrell of Dunster Castle and his younger brother Thomas, Rector of Minehead, who both deplored the way John supported and organised their poorer tenants to question their despotic rule … and eventually the Luttrells managed to get rid of him.

From Minehead John moved to Highbridge in the parish of Burnham-on-Sea where navvies were building the Glastonbury canal. And this was the place where another family tragedy happened. On a hot day in July 1833 John junior, aged 13, who couldn’t swim and had got into difficulties cooling off, alone, in the river Brue near Churchland Farm, drowned. Losing two of their children in their teens within a space of 3 years must have devastated John and Mary, who probably wanted to get away, and Opie Smith kindly invited them to stay with him at Westfield in Bath. And at the end of September 1833 the deacons of Twerton Chapel, just South of the river, who had recently separated from John Porter’s church in Bath, offered him £40 a year to settle with them. John stayed as Pastor at Twerton until December 1835, then left after a battle with the deacons, already mentioned above, over the strictness of membership rules. But he stayed in Bath and continued to preach at the many nearby chapels. But before 1841 he and Mary had moved again, to Lessness Heath in Kent, taking their granddaughter Julia with them. Lessness was John’s last pastorship before Amersham, and very little is known about it. Possibly they wanted to be within easier reach of Julia’s mother, who had found work in London.

Life in Amersham

It appears that neither of Amersham’s Baptist chapels had a manse in those days. John and Mary’s lodgings seem to have been in Chapel (or Meeting) Yard, which was, and still is, approached from the High Street through the archway beside the shop that then belonged to Thomas Morten, the Chemist and Druggist in High Street (afterwards Haddons). In the 18th century this was the house of Amersham’s Baptist Minister Richard Morris (1747-1817) which was registered as a meeting house for the Baptists, and the “Lower Meeting” House (now King’s Chapel) was built in 1785 on Morris’s land behind the house.

It appears that neither of Amersham’s Baptist chapels had a manse in those days. John and Mary’s lodgings seem to have been in Chapel (or Meeting) Yard, which was, and still is, approached from the High Street through the archway beside the shop that then belonged to Thomas Morten, the Chemist and Druggist in High Street (afterwards Haddons). In the 18th century this was the house of Amersham’s Baptist Minister Richard Morris (1747-1817) which was registered as a meeting house for the Baptists, and the “Lower Meeting” House (now King’s Chapel) was built in 1785 on Morris’s land behind the house.

Behind the shop now is a warehouse and behind that two tall houses, from whose upper floors the martyrs’ field can easily be seen. In 1841 George Washington Morris (1795-1867), Richard Morris’s son, was living in one of them. He was a Brushmaker (like his father and his mother’s father) who stayed a bachelor until he was 46, and in 1841 he lived alone with a housekeeper. Later that year he married Sarah Ainsworth (1794-1878), and in 1851 they shared their home with his brother Richard and three lodgers.

In the other house lived a chairmaker Thomas Dumbarton (1795-1863) and his wife Isabella (1795-1877) with their family. Eight of them in 1841, five in 1851. Isabella was a nurse. She looked after John Cocks in his last illness from Summer to December 1850, and it was she who registered his death. Probably John and Mary Cocks lived in rooms rented from the Dumbartons. In 1846 John wrote in the Baptist Reporter The field where poor Tilsworth was burnt … anciently called Stanly close … now known by the name of Ruckles … is opposite my house, and I often look at it with mingled emotions of grief and indignation. Kelly’s Directory for 1844 confirmed John’s address as Chapel Yard.

In Amersham John was at last able to enjoy more time for reading and study, and he began to write to the Baptist Reporter, at first, in 1843, reporting events at the Upper Meeting:

Two young men, who bid fair for usefulness in the church of Christ, were baptised in the Upper-meeting, Amersham, by Mr. John Cocks, pastor of the church assembling there. We trust this is the beginning of good days to this church, which has, for some time, been in depressed state … without a pastor for a long time. We have now cause to thank God and take courage, as our congregation is increasing, and many are inquiring the way to Zion.

John continued this same article with his own version of the well known story of the Amersham Martyrs, and speculation about whether or not they could be called Baptists. He seems to have enjoyed exploring the history of the town, but he wrote nothing new, except that the end of the article he made a useful statement about the Upper Meeting trust deed (now lost) :-

The trust-deed states that there are to be four deacons, two of whom are to be Baptists and two Paedo-baptists; so that the church is composed of baptised believers and infant sprinklers! Amersham, J.C.”

Four deacons seems a large number for such a small group. The names of John’s four Upper Meeting deacons have been lost, but it would be good to discover who they were. Perhaps two guesses might be made from John’s letters; Sampson Toovey the Chairmaker (1783-1860) and his son John Toovey (1807-1873), both of whom are mentioned in John Cock’s letters. Possibly also William Spratley (c.1786-1849) and his son John Spratley (1812-99) both Butchers, and also I think the Hosts at the Elephant & Castle? Another Upper Meeting deacon was probably Thomas Dumbarton (1797-1863) John’s landlord, whose daughter Sarah married Sampson Toovey’s son Henry (1822-?) Furniture Broker, of what is now 49 High Street (The Museum).

In 1846 John’s articles about the antiquity of the Baptist Church in Amersham were unfairly criticised by another regular contributor, Peter G. Johnson, the Town Missioner of Saffron Walden, who cast doubts on the basis of John’s claims, and also, infuriatingly, on John’s education and intelligence. It is unlikely that the two men actually knew each other. John’s reply read thus:

From the “confident tone” in which P.G.J. writes, one might conclude that he is the keeper of the records of all the baptist churches in Great Britain. Let him produce the documents. P. J. “having set his intelligent readers (for whose edification does he write?) all right,” he sits down in his easy chair, and with self complacency seems to say, “Now then, I feel it unnecessary to prosecute the subject further. I have enlightened the intelligent reader, and corrected the ignorant scribbler of church history, and the question is for ever set at rest.” I must confess that I am not yet satisfied that he has made all right.

A surviving letter (retained by the author) dated 1 March 1847 to George and Hephzibah Youatt from John Cocks (Hephzibah’s father) in Amersham (where he was the Baptist Minister) was addressed to Mr. G Youatt, Pianoforte Maker, 3 Stanhope St., Hampstead Road, London. He wrote that Mary (70) and granddaughter Julia (11) who was still living with them, had been ill but were better. He added

Many of our congregation are ill and feel the pressure of the times … in consequence of the severe weather our Congregation has been small and the collections have fallen off.

A lot of businesses and banks were collapsing after the end of the railway boom, and the winter of 1846-47 was noted for severe frosts and heavy rains across southern England.

The same letter also mentioned Glove Maker John Chappell of Torrington who had been one of the passengers waiting inside the Torrington bus, drawn up on Bideford Quay, when the horses became restive and backed the cab into the river, drowning all the occupants. I fear [he] was not better prepared for eternity than his poor Brother that I attended on the gallows at Exeter. It is an eternal disgrace to Bideford for their neglect of that dangerous quay.

The same letter also mentioned Glove Maker John Chappell of Torrington who had been one of the passengers waiting inside the Torrington bus, drawn up on Bideford Quay, when the horses became restive and backed the cab into the river, drowning all the occupants. I fear [he] was not better prepared for eternity than his poor Brother that I attended on the gallows at Exeter. It is an eternal disgrace to Bideford for their neglect of that dangerous quay.

Two of John’s letters, written in June and December 1849, are now in Amersham Museum, kindly donated by the author, complete with transcripts. They were written to his daughter Hephzibah and her husband in London, and mention Tooveys, Spratleys and Stathams. Also Thomas Morten opening (or expanding) his shop, and a public protest against Brooks the Relieving Officer.

On 10 Dec 1849 John Cocks wrote to George and Hephzibah Youatt in London:

We heard from Jemima last week, she seems to succeed in the school they numbered 40 when she went and now they have 81 she improves in writing and diction. The instruction she received from Miss Greenfield was of great service to her and I don’t doubt but she will become an efficient teacher. The Baptist Church at Bourton is a very respectable Church, and she has some superior companions so that by this she has an opportunity of improving herself. Mr and Mrs Statham are very kind to her.

Mary Greenfield was Mistress of the British School in Amersham. John Statham (1790-1863) Minister of the Baptist Chapel in Bourton at that time, was born in Amersham, so he was probably the person who arranged for Jemima to go and teach at the school in Bourton. His wife was Fanny (1808-after 1861) and in 1861 I think they were back in Buckinghamshire and John Statham was the Minister at Chenies, but the Statham family were numerous.

Figures published in 1851, but collected in 1850 while John was still alive, recorded services and attendance figures at all places of worship in Amersham. The Parish church, which seated at least 600, had Services and Sunday schools morning, afternoon and evening. The Methodist church had two services but no school. The two Baptist meeting houses provided the same services as the parish church, without evening schools. The Lower Meeting probably seated 350 and the Upper Meeting 80. The two Lower Meeting Sunday Schools (morning and afternoon) catered for about 150 children, and the Upper Meeting schools had about 30 each.

On 12 December 1850 John Cocks died aged 67. Mary (then aged 73) was helped with the nursing by Isabella Dumbarton, who registered his death. The Baptist Reporter January 1851 printed [p.44]

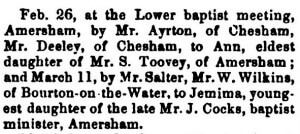

A note in the Cocks family bible says that John was buried at Amersham Bucks. His grave must be in the burial ground behind what is now the Kings Chapel, at the top of the path from Chapel Yard to the Platt, and the service was probably conducted by his fellow minister, Revd. William Salter (who also officiated  at the marriage of John’s daughter Jemima three months later.) Jemima, a schoolmistress in Gloucestershire, who probably returned to Amersham immediately after her father’s death, to comfort her mother, married Thomas Wilkins of Bourton on the Water on 11th March 1851.

at the marriage of John’s daughter Jemima three months later.) Jemima, a schoolmistress in Gloucestershire, who probably returned to Amersham immediately after her father’s death, to comfort her mother, married Thomas Wilkins of Bourton on the Water on 11th March 1851.

The Baptist burial ground has now (2016) been cleared to a bare lawn, with some of the headstones used as paving. Sitting on the seat looking north across the Misbourne valley, towards the Martyrs Field on the hill beyond it seemed (to his great great great granddaughter, who has inherited his bible) a fitting resting place for a man whose life was devoted to the salvation of Protestant souls.

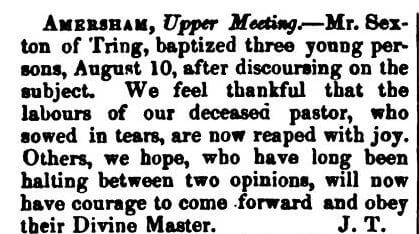

John Cocks had not been replaced eight months after his death in August 10 1851, when the Baptist Magazine printed a report that Mr Sexton of Tring baptized three young people of the Upper Meeting Amersham.

Probably the Upper Meeting membership was too small to afford another Pastor, but they hoped to expand. Who was J.T.? Probably John Toovey, Chairmaker, eldest son of Samson Toovey.

By 1861 John Price had succeeded William Salter at the Lower Meeting, but nothing can be found to indicate who succeeded John Cocks as Pastor of the Upper Meeting. The 1861 census lists a lodger at the home of Sampson Toovey’s son James and his wife. He was Thomas George Davison Bell, Unmarried Dissenting Minister, aged 24, born in Gatehead, Durham. He seems to have been a Congregational minister in Cumberland who went to Nebraska in 1867, so his stay in Amersham must have been for something else.

After John’s death, Mary stayed for a while in Amersham, lodging with Miss Jane How in the High Street. But eventually she went to live with Jemima in Bourton in the Water, where she died in 1857. Her grave, which she shared with an infant granddaughter, is marked Mary COCKS, widow of the late Rev’d John COCKS of Amersham, 14 Oct 1857, 80