By Nick Gammage

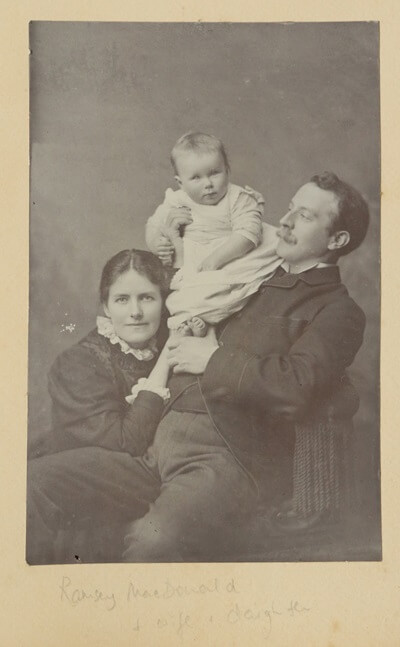

Striking photographs in a newly discovered Edwardian album bring to light a previously unrecorded friendship between the families of Labour Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald and his wife Margaret and their Chesham Bois neighbours, social campaigners Francis and Sophie Colenso of Elangeni.

The album, which once belonged to the Colenso family, has now been acquired by Amersham Museum through a generous gift from the Amersham Society. Alongside powerful portraits of the Colensos’ at their now long-demolished home Elangeni sit a remarkable group of photographs from around 1906 of Ramsay and Margaret MacDonald and their young children haymaking with the Colensos at Elangeni.

The Colensos of St John’s Wood built Elangeni on farmland in 1901 as a country home and in March 1905 the MacDonalds’ rented Linfield cottage in Bois Lane – also as a weekend retreat (1). The two families’ connections with Chesham Bois and their pioneering social campaigning have been well-documented in articles on Amersham Museum’s website (2). But what has not been known before now was that these influential Chesham Bois neighbours were also good friends.

Research in the MacDonald and Colenso family archives (3) prompted by these photographs uncovered many letters which reveal that this was a warm and lifelong friendship which spanned more than 30 years. In a letter to Ramsay MacDonald’s son Malcolm in June 1935 to congratulate him on his promotion to the Cabinet as Colonial Secretary (4), Sophie looked back on the long and close association between the two families:

“Remembering what a help your father was to Mr Colenso in his struggles for justice for the S. African natives, I feel the Colonies can safely be left in your hands”

and she signed off:

“Your old (very old!) friend, Sophie J Colenso”

Other letters reveal that in fact the two families knew each other well before the MacDonalds leased Linfield in 1905, which makes it possible that the Colensos were behind the MacDonalds’ choice of Chesham Bois for a weekend retreat. Sophie’s father Sir Edward Frankland (1825-1899) and Margaret’s MacDonald’s father John Hall Gladstone (1827-1902) were among the most eminent Victorian scientists and were friends, their families often visiting each other. Sophie tells MacDonald that Margaret’s sister Florence (his sister-in-law) had been her bridesmaid in 1880 and reminds him that she and Frank had first met him at the home of Margaret’s father. This must have been after Ramsay MacDonald first met his future wife Margaret Gladstone on 13 June 1895 (5) and before Gladstone’s death in 1902 – at last three years before they rented Linfield.

The MacDonalds and Colensos were bound not just by social campaigning but by the shared experience of a series of devasting family tragedies. Condolence letters in the MacDonald archives sit alongside a silk ribbon that once tied a child’s funeral wreath, which make the photographs of those carefree young children and their mother in the hay meadows even more poignant.

The album contains two intimate photographs of four of the MacDonalds’ six children. As a number of photos carry the dates 1906 and 1907 it is likely these are Alister (born in 1898), Malcolm (1901), Ishbel (1903) and David (1904). Joan was to arrive later (in 1908) and their sixth child, Sheila, in 1910.

In February 1910 the MacDonalds suffered the devasting loss of their five-year-old son David from diptheria in the London Fever Hospital. Frank and Sophie knew all too well what it was to lose a young child: in July 1882, their first-born Esmond had suddenly taken ill and died aged just seven months at her parents’ home in Reigate.

children

Sophie and her daughter Irma both sent messages of sympathy to the MacDonalds, with Irma (then aged 24) recalling the MacDonalds’ happy family visits to Elangeni with their children:

“Much as I love all year dear children, little David always held the biggest place in my heart and we shall never forget his sweet loveable ways. The hours we have spent with your dear little ones are among the happiest in our lives and we shall miss his dear little face from among them more than I can possibly say.” (6).

The card attached to the ribbon which tied the Colensos’ funeral wreath reads: “In ever loving memory of our darling little David, from Mrs Colenso, Eothen, Irma and Sylvia”

More tragedy was to come. Four months later in June 1910 Frank died at Elangeni, aged just 58 (7). In September the following year Ramsay MacDonald, too, was suddenly widowed when his wife Margaret died aged just 40 after contracting blood poisoning, leaving five children.

Two years after that, in 1913, Sophie Colenso lost another child prematurely in tragic circumstances when her only surviving son Nigel, aged 23, was killed in a shooting accident in South Russia while working as a mining engineer. There are striking portraits in this album showing Nigel in his later teens, astride an early motorcycle and on horseback. He was the image of his father.

The MacDonalds and Colensos were drawn together too by their campaigning on a number of pressing social issues, most notably in favour of women’s suffrage, against the worst horrors of war and against the treatment of native tribesmen in Britain’s South African colonies.

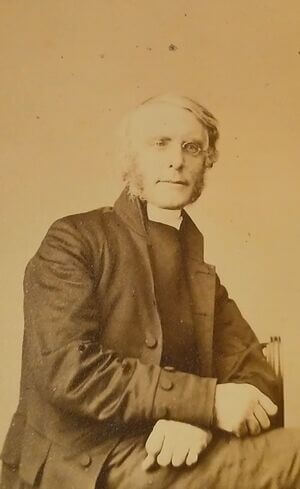

Francis (Frank) Colenso (1852-1910) was the son of the controversial Bishop John Colenso (1814-1883), first Anglican Bishop of Natal and tireless campaigner for the Zulus against what he saw as ruthless British colonial rule. Frank, working in London, lobbied Parliament and the British Government tirelessly on the Zulus’ behalf. This lobbying intensified in March 1906 (the period of that idyllic Elangeni haymaking) following the Natal government’s over-reaction (a view many shared) to a native revolt against a harsh new Poll Tax. The self-governing colony arbitrarily declared martial law, arrested the Zulu rebels, tried them without a jury in courts martial and condemned twelve to death.

The MP through whom Frank channelled his efforts for the condemned Zulus was none other than his new Chesham Bois neighbour James Ramsay MacDonald, then a rising star in the fledging Labour Party, newly elected in 1906 as a Member for Leicester.

There can be no doubt that the MacDonalds shared, passionately, the Colensos’ concern about what was happening in Southern Africa. In 1902 Ramsay and Margaret had visited South Africa in the aftermath of the Boer War and were appalled by what they saw. MacDonald’s vivid account of that journey (8) carries harrowing accounts of the trenches and indiscriminate revenge-burnings of Boer farms by British troops, which clearly forged his life-long belief that war achieves nothing.

There is a stark personal reply from MacDonald to Frank Colenso dated 30 March 1906 in which he “privately” reveals what Winston Churchill (Churchill then a Colonial Affairs Minister in the Liberal Government) thought of how the Natal colonial government was behaving.

“The whole situation is most critical. I had several interviews with Mr Churchill yesterday upon his invitation and I can assure you privately that he is really in a great state about it.” (9)

It is not clear from the letters whether Frank began canvassing Ramsay MacDonald’s support after the two men became Chesham Bois neighbours in 1905 or whether they had discovered their shared interest before that.

Pacifism, another shared interest, was of growing importance through MacDonald’s political career and his refusal (initially) to support Britain’s decision to declare war against Germany in 1914 brought him vitriolic criticism. The war raised complex issues, too, for Sophie Colenso. Her mother was German, she and her children bi-lingual and they made regular visits to German relatives and friends. Census returns show the Colensos employed German servants at Elangeni.

From the outbreak of war Sophie urged MacDonald to take up the plight of German interns and German Prisoners of War. He explained that while he was sympathetic, he could not do this publicly without him appearing even more pro-German than he was already being painted. In a reply to Sophie from November 1914 about conditions in internment camps he refers to picking up her letter at Chesham Bois. This indicates he was still renting Linfield cottage at the outbreak of the Great War, a decade after first leasing it.

MacDonald and Sophie Colenso died within a few months of each other in 1937. MacDonald never lost his love of Elangeni and Chesham Bois. Writing to Sophie shortly before his – and her – death that year he describes fondly catching sight of Elangeni just a few days earlier as he walked down a road to the west of Chesham Bois, passing under the railway bridge (10) and walking beside the watercress beds on his way to Chenies.

The photographs in this album provide us with our clearest picture yet of the Colensos and their long-demolished home Elangeni in its heyday (or perhaps haydays!). They also bring to life, vividly, an enduring relationship between “very old friends” in two remarkable families.

Notes

- Ramsay MacDonald describes taking the lease on Linfield in March 1905 in Margaret Ethel MacDonald (Hodder and Stoughton, 1912), a memoir of his late wife published a year after her death.

- See: Margaret And Ramsay MacDonald by Alison Bailey: https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/20th-century/margaret-and-ramsay-macdonald/

MacDonald Family by Alison Bailey: https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/20th-century/mac-donald-family/

The Colenso Family at Elangeni by Nick Gammage: https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/19th-century/colenso/ - Ramsay MacDonald’s personal papers are held at the National Archives, Kew. The Colenso family papers are at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Malcolm MacDonald’s correspondence, drawn on for this article, is held at the University of Durham.

- Ramsay and Malcolm MacDonald were only the third father and son in British politics to have both held Cabinet posts.

- See Ramsay MacDonald, a biography by David Marquand (Jonathan Cape, 1977), page 44.

- Irma Colenso to Ramsay and Margaret MacDonald (letter dated 11th February 1910)

- 7.In a manuscript letter to the Zulu chief Zinuzulu after Frank’s death, Sophie writes that his “fatal illness” had been brought on by tireless campaigning. “This want of rest & great strain – the work and the heartache over your sorrows and those of your people wore him out at last.” (undated)

- What I saw in South Africa, September and October 1902 by J Ramsay MacDonald (The Echo, 1902)

- Typed letter from Ramsay MacDonald to Francis Colenso, dated 30th March 1906.

- This may be the railway bridge over Hollow Way Lane, Chesham Bois, which carries the Metropolitan Railway between Chesham and Chalfont and Latimer. The other “over bridge” in that area carries the railway over a path descending through Blackwell Stubbs to the Latimer Road which is a track rather than the “road” MacDonald describes.