Bible-reading was central to the religious practices of the Baptists and other nonconformists. This meant that literacy was a highly valued skill in relation to salvation and underpinned the drive towards ensuring that education was available to all. The desire to distance themselves from the Church of England and to run their affairs themselves was particularly strong in relation to education as the influences children were subject to and the instruction they received would be with them for the rest of their lives.

Many of the Amersham Baptists were self-employed men, used to making their own decisions and proud of their independence. At a time when most of them lived in houses owned by the Drake family, in a parish served by an ordained member of the Drake family and, if they went to a magistrate’s court, could find themselves in front of one or more members of the Drake family[1], there may have been a particular satisfaction in setting up a school of their own.

In the past many children put out to work from an early age, had got such book-learning as they could from the Sunday Schools. In the early nineteenth century the influence of the Sabbatarian movement was widely felt and restricted what could be learnt in such schools. Reading could be taught as it gave access to the Scriptures, so had a godly purpose. A knowledge of writing gained at Sunday School might, in contrast, be exploited for commercial purposes if used to earn a living and thus might profane the Sabbath.[2]

Successive governments, for many years after the French Revolution, were fearful that similar uprisings could take place in Britain. Educating the children of labourers might make them discontented with their lot in life, ‘even worse, the acquisition of literate skills would make the working classes receptive to radical and subversive literature.’[3] Such views were countered by those who urged that literacy was essential for the efficient functioning of an increasingly complex urban and industrial society in which people needed to understand indentures, bills of lading, safety regulations and advertisements for jobs, to say nothing of all the other benefits of education.

The General Register Office was in a position to collect some indicative statistics on literacy. That education was being closely linked in some people’s minds in the 1840s to social improvement is strongly implied in the Eighth Annual Report of the Registrar-General dated 25 March 1847 (p 33) when he considers the number of people who between 1839 and 1845 had had to make their mark on their marriage certificates because they could not write their names. In 1842 the figures were 38,031 men and 56,965 women. The total number of couples married that year was 118,825.

‘The serious fact remains, that there is no evidence that any improvement in the mere elementary education of the people took place in the period when the men and women married in the seven years, 1839-1845, were educated; and that the state of education was such that in 4 in 10 English man and women could not write their own names. The state of education differs in different counties. And it has recently been shown, in an analysis of the Criminal Returns, compared with the facts published in previous Reports, that crime is most prevalent in the districts where in proportion to the whole the fewest numbers can write. “It is found, that out of 22 different combinations formed of the various districts of England and Wales, in every instance there is an excess of crime where there is the least education or instruction; and, comparing the respective sections of each group of counties, it will be seen that there is an average excess of 25% of crime in the sections of inferior education over that of higher education; and in some districts the excess is as much as 44%”.’

The figures are then further broken down by county with Buckinghamshire coming low on the list with 43% of men and 55% of women unable to sign. Curiously the two best are the Metropolis and Cumberland, returning 12 & 16% for men and 24 and 36% for women.

Fears about the loyalty to the state of those who refused to conform to the 39 articles of the Established Church had come through from Tudor times and had principally borne down upon Roman Catholics. When Elizabeth I was excommunicated by the Pope, where did their true allegiance lie? Suspicions were reawakened at intervals by a succession of political events — the Spanish Armada, the Gunpowder Plot,[4] the Jacobite Rebellions of 1715 and 1745, and in the Gordon Riots of 1780 many houses belonging to Catholics had been destroyed in London. The French Revolution, in contrast, meant that some protestant nonconformists instead fell under suspicion because of their support for egalitarianism:

‘They [the Methodists] do a great deal of harm, they pretend to great sanctity, but it is ostentation, not reality. They draw people from the Established Church, infuse prejudices in them against their legal Pastors and of late they are all Democratic and favourers of French Principles.’[5]

In the early years of the nineteenth century most elementary education was provided by voluntary societies. This consisted of ‘the three R’s’ (Reading, Writing, ’Rithmetic) but a fourth R, Religion, was crucial. The fears of those who thought that the three R’s would simply

encourage radicalism and revolution were allayed by ensuring that there was a strong moral message also. This, of course, led to disagreements about who should provide it. Parish schools run by the established church were viewed with suspicion by nonconformists.

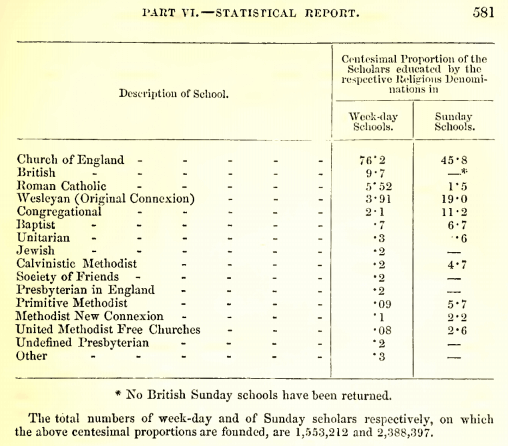

The two largest voluntary providers of education were the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, which had a Royal Charter, and the British & Foreign Schools Society, which set out to be non-denominational and therefore appealed to many dissenters. Others had their own denominational schools as can be seen below:

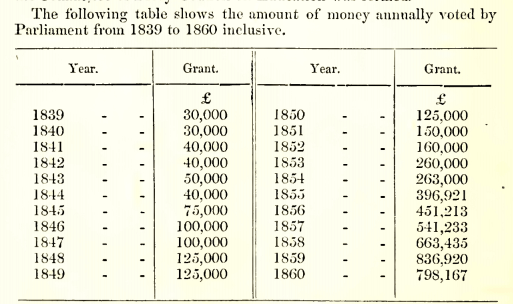

The government had begun to channel money in the direction of the voluntary societies from 1839 and this had risen steadily:

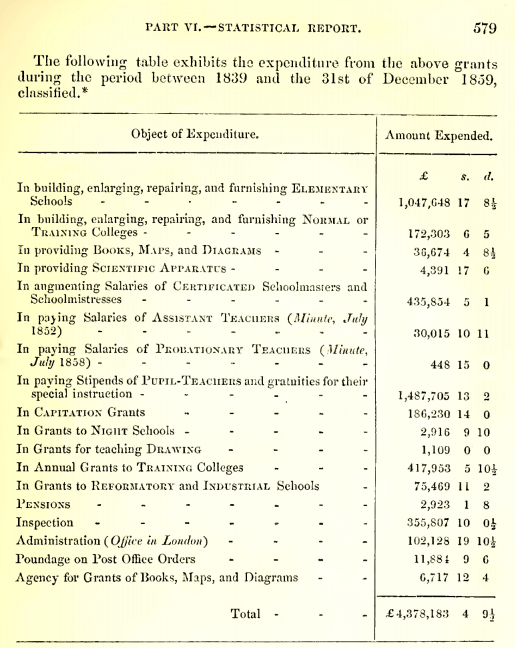

The money had been laid out as follows:

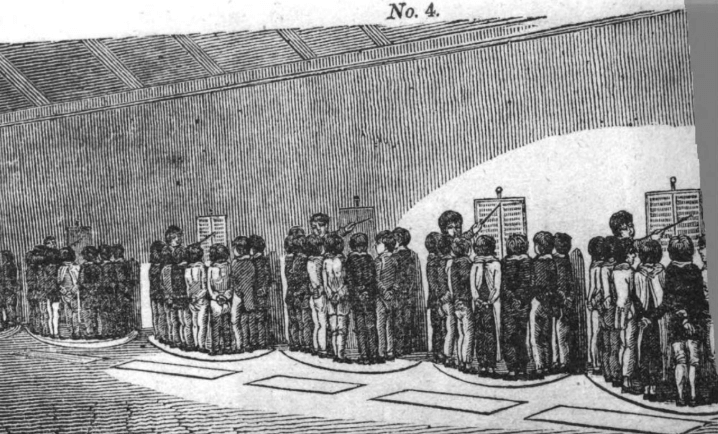

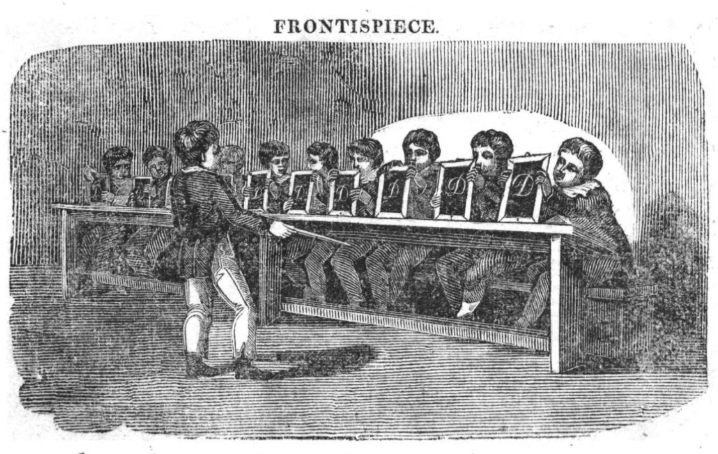

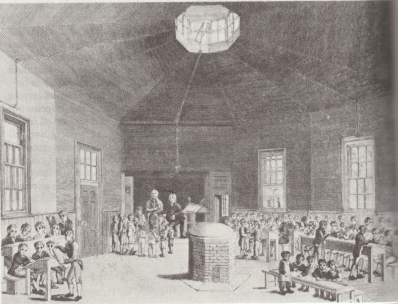

The British and Foreign Schools Society had been founded in 1808 and the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in 1811. Both were organized along similar lines. Dr Andrew Bell, superintendent of The Military Orphan School in Madras in 1792, and Joseph Lancaster, a young and energetic Quaker in Southwark in 1796 faced the same problem — how to educate large numbers of children with few resources? Lancaster, aged only 19, had attracted 90 children and the number grew ten-fold over the next two years. The solution for both men was to teach a few of the older children, then set them to teach others. So both schools used what became known as the monitorial system.

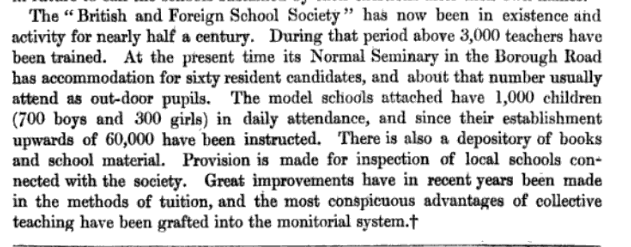

Management of the Lancasterian schools passed into the hands of the BFSS when Lancaster, whose talents as an administrator lagged well behind his power to inspire, ran into debt. The schools were run on ‘an unsectarian basis — no particular religious tenets being inculcated; the “Bible without note or comment” being the only religious school-book.’[6] Their success led Anglican churchmen to set up the National Schools, with Dr Bell as the first Superintendent. The table shown earlier proves how successful this was, with 76.2% of those in school by 1859 being in National Schools and 9.7% in the British School system.

Large schools were divided into sections of about fifty pupils, then taught in drafts of ten to fifteen. For writing ‘the children of the lowest section are employed on slate, with pieces of slate-pencil inserted in pencil-holders. The position of body and hand, the forms of letters, and the elementary principles of writing are thus taught before the expense of writing on paper is incurred. Children should not, however, be kept from copy-books longer than is absolutely necessary; the additional trouble entailed by the use of pen, ink and copy-book, is more than repaid by the better means of training and improvement which they afford.’[7]

In 1814 the Bishop of London memorably declared: ‘Every populous village unprovided with a National School must be regarded as a stronghold abandoned to the enemy.’[8] His view then was that ‘the great instrument of education is at present in the hands of the church, every effort to wrest it from them has hitherto been in vain.’

A high proportion of education had been provided through parish schools, schools staffed or headed by members of the clergy (such as Dr Challoner’s), or through schools provided by large landowners who overwhelmingly were members of the established church. But dissent was growing:

‘In this unfamiliar setting [the industrial revolution] Protestant Nonconformity fared remarkably well. Between 1772 and 1851 its total of worshipping congregations multiplied tenfold. Its numbers more than kept pace with population growth. Whereas in 1715-18 Nonconformists formed about 6 per cent of the population, in 1851 they constituted some 17 per cent in England and no less than 45 per cent in Wales. At the religious census of 1851, the only official return of worshippers ever undertaken in England, Nonconformists were shown to be not far short of half the churchgoing population. It was an astonishing achievement.’[9]

By 1841 the British Schools were well established and growing:

It was to the Normal School, often called Borough Road College, in Southwark, that Ebenezer West would write when teachers were needed for the British School in Amersham. British Schools were run, as in Amersham, by a local committee and these were usually described as being ‘in union’ with the BFSS. This gave a sense of shared purpose without removing control from local communities. The BFSS could supply not only trained teachers but teaching materials as well and the Annual Report contained a list of what was available.[10]

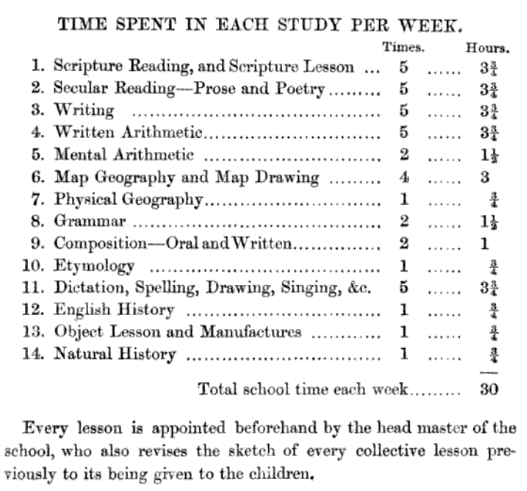

Some idea of what went on in the Model Schools where the student teachers did their teaching practice can be gained from the specimen timetable of 1856. The school is divided into three groups and school hours are from 9 to 12 and 2 to 5:

Initially teacher-training at the Borough Road College was for quite short periods, with junior and senior courses being offered, each lasting three months. Not all students took both.[11]

Benjamin Armstrong, Vicar of East Dereham, reflected with pleasure on 29 June 1864 that he had managed to obtain a post as pupil-teacher for a local girl ‘otherwise she would have been a maid of all work’, but the indentures of another girl were cancelled by her father on the grounds that her health would not stand up to the work.[14]

FH Spencer describes how he was set on this path by his father (confessing that, had he been asked, he would rather have been an engine driver): ‘My father was one of the type of skilled artisan not by any means uncommon, men of intelligence with intellectual interests which they are only partly able to exercise. “Going to college” appealed to him, and he hardly discriminated between Balliol or Trinity and a Training College for Teachers then in the back streets of South London. Moreover, I should not have to tumble out of bed at 5.15 in the morning in winter to ‘be at my work’ by 6; and there would be more than a week’s holiday in the year. So a pupil teacher I became.’[15]

Pupil teachers found that they had to work extremely hard. Mrs Burgwin, later Head of Orange Street Board School in London, remembered ‘the five years which I spent as a pupil-teacher as being the hardest period of life that a girl can possibly have. I had to give up, during those five years, both music and painting…..because the work was so heavy and we had so many home lessons to do.’[16]

Those who did well in their exams were awarded a Queen’s Scholarship and could proceed to a Normal College for up to three years’ training. Success brought a state-recognized qualification, the Teacher’s Certificate, first awarded at Borough Road College in 1851. Exams were held at BRC in English Grammar, History, Geoography, Arithmetic, Geometry, Algebra, Reading, Penmamship, Physical Sciences and Singing.

As will become apparent the Amersham Committee was very conscious of how schooling could improve the life chances of children who were able to access it and for nonconformists a British School was an attractive choice.

[1] The Reverend Henry Beddow, Baptist Minister, and Samuel Toovey, for many years Deacon of the Upper Baptist Chapel, had to settle their differences following a brawl in the chapel at the Amersham Petty Sessions presided over by the Rev ET Drake, Rector, and Captain Drake. See the South Bucks Standard, 3 March & the Bucks Herald of 4 March 1893.

[2] WB Stephens, Education in Britain 1750-1914, 1998, p 5

[3] Michael Sanderson, Education, Economic Change and Society in England 1780-1870, 1995, pp 12-13

[4] Until 1859 the Book of Common Prayer included a service ‘for the happy Deliverance of King James I, and the three Estates of England, from the most traitorous and bloody-intended Massacre by Gunpowder.’

[5] Ed Jack Ayres, Paupers & Pig-Killers, The Diary of William Holland, a Somerset Parson, 1799-1818, 2003, p 33, entry for 11 May 1800

[6] Census of Great Britain, 1851, Education in Great Britain, being the Official Report of Horace Mann, of Lincoln’s Inn, Esq, Barrister-at-Law, to George Graham, Esq., Registrar-General, London, 1854, p 12. See https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=xTcIAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false For an outline of Dr Bell’s career see https://www.raggeduniversity.co.uk/2012/10/31/andrew-bell-1753-1832/

[7] A Hand-Book to the Borough Road Schools; Explanatory of the Methods of Instruction Adopted by the British and Foreign School Society, 1856, pp 5 & 7

[8] William Howley, Bishop of London 1813-1828, was afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury. His ‘Charge to the Clergy’ of his See was printed in the British Critic and Quarterly Theological Review, 1815, Vol 3, p15. See also WB Stephens, Education in Britain 1750-1914, 1998, p13. The earliest known schools in Britain were choir schools attached to cathedrals, such as Kings School, Canterbury, founded in 597 and Kings School, Rochester, in 609.

[9] Ed David Bebbington, Kenneth Dix & Alan Ruston, Protestant Nonconformist Texts: Vol 3 The Nineteenth Century, 2006, p 1

[10] See Appendix 3

[11] BFSS Archives Info Sheet no 3, Stockwell College, p2

[12] It is not clear where it is now held. Searches of the catalogues of London Metropolitan Archives, Collage, AIM25 and the Institute of Education have proved negative. An example was sold by Bonhams on 1 April 2008. Lambeth Archives has an engraving of the exterior of the school attributed to Bartholomew Howlett and dated 1813 (ref: SP22/171/CLA.1 and online https://boroughphotos.org/lambeth/clapham-parochial-school-old-town-clapham/). They seem to an untutored eye to be very similar in style. Other octagonal schoolhouses survive in Mildenhall, Wiltshire, Cowgill’s Corner, Delaware, and Birmingham, Pennsylvania.

[13] Pamela Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 1989, p 167. See also BFSS Archives Info Sheet no 2, Borough Road College, p2 & no 3, Stockwell College, p2

[14] Susanna Wade Martins, A Vicar in Victorian Norfolk, the Life and Times of Benjamin Armstrong (1817-1890), 2018, p153-4

[15] FH Spencer, An Inspector’s Testament, 1938, pp74-5

[16] Pamela Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 1989, p 167, quoting from the Royal Commission on the Working of the Elementary Education Acts, Parliamentary Papers, 1888, Vol XXXV, Q 17, p 188