Refusing to conform to the beliefs and practices of the Established Church had for several centuries involved penalties. Active persecution had ceased but civil disabilities remained. These were gradually disappearing.

In 1828 the Test Act of 1661 and the Corporation Act of 1673, designed to prevent nonconformists from holding public office, were repealed. Their provisions had been widely ignored (indeed an Act of Indemnity had been passed annually so that they could be safely flouted) but their continued existence had angered nonconformists and put successive governments in the undignified position of proposing that legislation should be ignored. The Reform Act of 1832 changed the social composition of the House of Commons and the election of a number of nonconformist MPs helped to bring about further significant changes.

Admission to the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge was restricted to Anglicans, so access to learned professions was barred. The founding of the non-denominational University of London in 1828 had begun to address this problem also.

The payment of tithes which had forced people who did not wish to be part of the Established Church to contribute to its maintenance was ended by the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. The resentment this produced had resulted in vehement denunciations:

‘In every ten years the entire produce of the land for a year is eaten up by the black-footed locusts, and the parties who principally consume this revenue, are the bloated Archbishops and Bishops, the lazy Deans and Sub-Deans, and the useless Canons and Prebendaries.’

This preacher, Matthew Tebbutt, was addressing an open-air meeting at Cottenham in 1834 and was clearly totally opposed to the Established Church:

‘The Church of England is the synagogue of Satan, and so far anti-scriptural and anti-Christian, that it will one day or other be eaten up by the breath of God’.[1]

The diary of John Skinner, Rector of Camerton, shows how baffled he was by the attitudes of the Methodists in his parish. He reports some very interesting encounters such as that on 16 February 1816. It is incomprehensible to him, a man of learning and authorized by both his Bishop and the state to run his parish that his parishioners should turn aside to other forms of worship. He was told that some Methodists had been

‘crying and bewailing their sins, and continued in that state until 11 o’clock at night. I replied that I was sorry to hear that they had suffered their feelings to be worked upon by the ignorant and designing; that it would be much better for them to come to Church to convince their reason and understanding, instead of suffering themselves to be misled by the heats of a disordered imagination.’[2]

On being told that the Methodists wanted to convert everyone in the parish and hoped to do so ‘ere long’,

‘I told them that it would be much better for such ignorant and uninformed persons as they were to attend to their own business as colliers and leave me to direct the souls of my parishioners which were committed to my charge; that it was my office to do so and that they had no place or pretence [claim] to take that office from my hands.’

They, on the other hand, were not inspired by the fixed liturgy, but responded much more readily to spontaneous prayers, to fiery preachers and to gathering in their own homes in small groups for Bible-reading, discussions and prayers.

The Reverend Skinner’s confrontations with his parishioners show that the gulf between them was not just one of differing points of view about forms of worship: there was also a social divide — he was educated and thought differently, lived differently and probably spoke with a different accent.

Amersham had long been drawn to puritan practices: a report made in 1624 to Dr Farmery, Chancellor of the See of Lincoln, stated that:

‘Notwithstanding the orders given by the Vicar General at the visitation of Amersham, no pews in this church have been taken away, or lowered, no doors leading to the churchyard stopped up, and the people still lie in their pews, sit with their hats on, and neither kneel at the litany nor bow at the name of Jesus. The names of those who kept a muster in the churchyard are given in, but the Deputy Lieutenants threaten vengeance on those who gave the information. Complains also of unnecessary delays in the baptism of infants, so that the sacrament is scarce thought one of necessity.’[3]

In 1662, following the restoration of the monarchy, use of the Book of Common Prayer was made mandatory so that worship within the Church of England followed a fixed formula. Many parish priests, including the Reverend John Phillips of Amersham, a Presbyterian, could not stomach these restrictions or the other changes which accompanied them. He had to be evicted from the Rectory[4] and so many other ministers were also forced to leave their parishes that this became known as the Great Ejectment.

The questionnaire sent out in preparation for the Visitation of 1709 showed that Amersham was still home to numerous nonconformists: ‘Families 400: souls 2,000; dissenters of all kinds, chiefly Anabaptists and Quakers; these meet every Sunday; in number the former of 70, the latter of 90. About one third of the parish are dissenters.’[5]

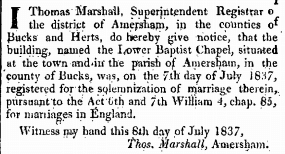

Following the accession of William of Orange to the throne, a measure of tolerance had been granted to protestant nonconformists (with the exception of Unitarians). They could now have their own chapels and burial grounds provided those were registered and licensed. This did not, however, bring full freedom from the Established Church. From 1754 to 30 June 1837 all marriages except those of Quakers and Jews had to take place in an Anglican church.[6] Many clergymen disliked having to marry couples who had not been baptized into their church. Conversely the calling of banns made many nonconformists feel as though their marriage was being subjected to the approval of a body whose authority they did not acknowledge. To avoid this they might be put to the extra expense of obtaining a licence or, like many Amersham couples, get married in a London church or one a little nearer, such as Hillingdon. From 1 July 1837 civil marriage before the Superintendent Registrar was possible without any religious ceremony.

Nonconformists could, if they preferred, be married in a chapel licensed for that purpose and in the presence of the local Registrar of Marriages. Apart from the mandatory declaration that they were marrying, the ceremony could take any form which was agreeable to the minister and, presumably, the bride and groom. Anglican marriages continued as before but with the priest acting additionally as registrar and producing quarterly returns for the local Superintendent Registrar.

On 7 July 1837 the Lower Baptist Meeting House was registered so that marriages could be performed there under the new legislation. This shows that the application must have gone in very promptly indeed. The Minute Book shows that members were informed on 4 August 1837 that this process had been successfully completed.

On 3 November the first marriage to be performed there was noted, that of Mr H Ainsworth and Miss Stratford. The pastor, the Rev J Statham, was away, so the Rev J Hall officiated. There does not appear to be any register of weddings performed at the Meeting House. Some announcements were made in the local press and some in the Baptist Magazine. By 1859 in such announcements the chapel is being referred to as the General Baptist Chapel, Amersham.

Until 1856 details of couples applying to marry by Superintendent Registrar’s certificate (which was cheaper than a licence) had to be read at three consecutive meetings of the Poor Law Union Board of Guardians. These were duly noted in the Board’s minutes. This process acted as the civil equivalent of the calling of banns in church and now provides a useful additional source for extra-parochial marriages. Once again Henry Ainsworth and Mary Stratford were first on the list.

Another problem for nonconformists was that their records did not have the same legal standing as those of the Established Church. An entry of baptism in an Anglican register was accepted by the courts as proof of lineage and of (approximate) age.[8] Legal advice had been taken before the Registry of Births was set up at Dr Williams’s Library[9] and the information recorded there (as any family historian swiftly discovers) is much more precise than that from a parish register of baptisms. It gives a precise date and place of birth and usually the names of two witnesses (often including a surgeon or midwife) who could attest to the arrival of the baby. As Baptists did not believe in infant baptism it was desirable to provide proof of age by this means, but many other nonconformists could also see the desirability of having a certificate. It was galling that in court these certificates could only be adduced in evidence but were not of themselves sufficient proof. Quite a number of Amersham Baptists made use of the registry at Dr Williams’ Library as well as setting out their own records with space allowed for the signature of witnesses.

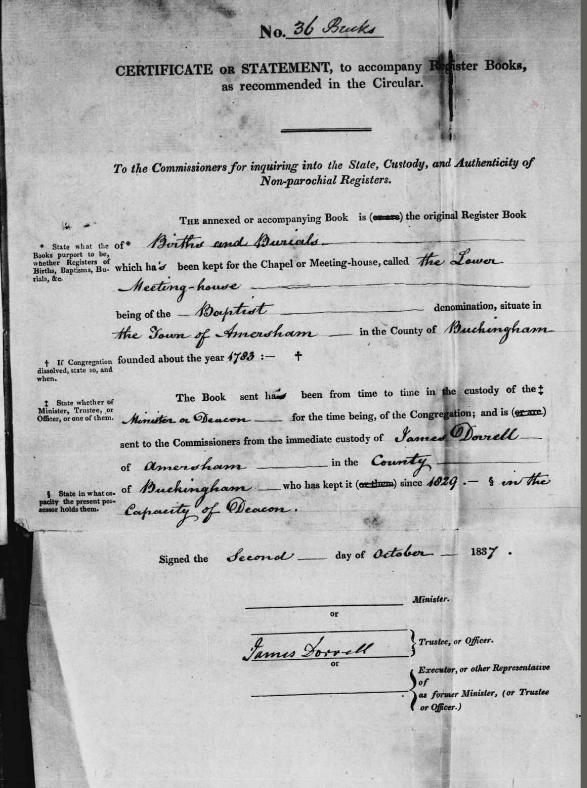

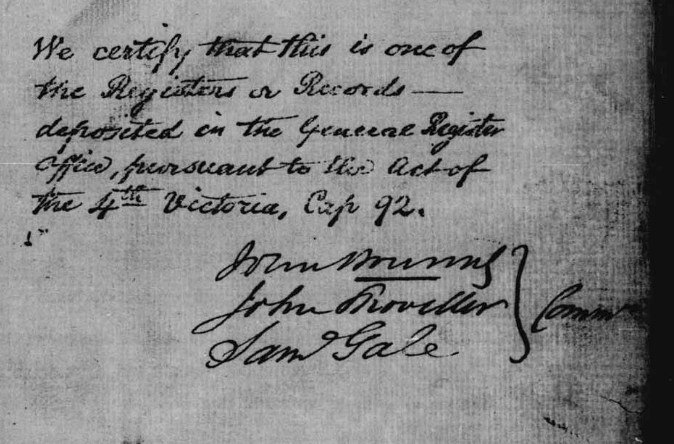

In 1840, once the system of civil registration was in operation, the Registrar General’s attention turned to nonconformist registers. If these were handed in and authenticated (that is, if the entries were made at the time the event was notified and were not copies made later and if the registers had been securely kept), then birth and other certificates could be issued.

The National Archives, London, England)

The National Archives, London, England)

All these were notable victories for nonconformists and must have whetted their appetite for further advancement.

Attitudes to the Established Church varied, from those who had no problem with attending church in the morning followed by chapel in the afternoon to the antagonism of those whose eventual aim was the disestablishment of the Church of England. It is probably fair to say that in many places people were very conscious of owing allegiance to either church or chapel and that this choice affected not just where they went on Sundays but impacted many of their activities. Of Long Crendon it has been said: ‘There were Church shops and Chapel shops, and people buying groceries would go out of their way to patronise one from their own religion. For the Sunday School outings there were church waggonnettes and Chapel waggonnettes drawn by Church horses and Chapel horses.’[10] Given the choice, the two communities liked to keep themselves to themselves and this was not only for worship.

The 1851 Religious Census shows that in Amersham the Baptists were the most numerous and active of the nonconformists. Attendance at the Quaker Meeting House was down to 2 on Sundays, while the Wesleyan Methodists had an attendance of 28 and no Sunday School. The Lower Meeting House, in contrast, could claim an afternoon congregation of 286, with 148 in the Sunday School, and 353 in the evening. The Upper Meeting House additionally had 78 Baptists in the afternoon and a Sunday School of 78.

Anyone reading the 1830 (and later) editions of Pigot’s Directory of Buckinghamshire and noticing frequent phrases like ‘the baptists are most respectable congregations, and their ministers highly respected’ must be led to wonder just what other sections of society expected of them? It seems likely that this is a reflection of sixteenth and seventeenth-century attitudes towards Anabaptists.[11] Their critics viewed them as a ‘danger to the whole fabric of our churches and kingdoms’[12] and remembered that the desire of some of them to separate from church and state had led in 1534 to the seizure of Münster which was intended to be the new Jerusalem.

By the 1840s, however, the Baptists were one of the three most numerous groups of Nonconformists and the time when they were viewed as dangerous and heretical subversives was long past. They were characterized by their preference for non-liturgical forms of worship, with a strong emphasis on prayer and preaching and their belief that baptism should only be administered to those who chose it and could profess their faith. This precluded infant baptism. Basing their practice on the New Testament, they also held that baptism should be by total immersion.

Their desire to run their own affairs independently of interference by the Established Church or the state extended also to the education and upbringing of their children.

[1] Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 28 March 1834

[2] John Skinner, Journal of a Somerset Rector 1803-1834, ed H & P Coombs, 1984, pp 92-94

[3] Calendar of State Papers Domestic, 1623-5, p 347

[4] http://amershamhistory.info/old-town/the-old-rectory-2/

[5] Ed John Broad, Buckinghamshire Dissent and Parish Life 1669-1712, Buckinghamshire Record Society, Vol 28, 1993, p 99. Visitations were being carried out every three years by William Wake, Bishop of Lincoln. Anabaptists [later shortened to Baptists] opposed the baptism of infants, believing that baptism could only be valid when administered to those who confess their faith in Christ and desire to be baptised.

[6] Quakers and Jews were exempted because of their exemplary record keeping. The issue was not a doctrinal one. It is clearly, if a trifle pugnaciously, explained by Owen Chadwick: ‘The dissenters wanted to be free to marry in their chapels. But their ministers were of insecure tenure, their chapels impermanent, their registers chaotic. The lawyers demanded legal safeguards for the correct registration of marriages and provision against clandestine marriage. The parish register reposed in the parish church and under the care of the parson. The rector or vicar was the nearest official to a modern registrar’, the Victorian Church, Part 1 1829-1859, 1992, p 143.

[7] Reproduced under Open Government Licence v3. For further details see http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

[8] For further detail see Peter J Bilbrough, ‘The Admissibility of Parish Registers as Evidence in Courts of Law’ in the Genealogists’ Magazine, Vol 17, 1973, pp371-376.

[9] A ‘General Register of the Births of Church of the Three Denominations’ [Presbyterian, Independent or Congregationalist and Baptist] dated from 1742. The College of Heralds instituted its own, more expensive registry in 1748 and the Wesleyans in 1818. For more detail see DJ Steel, The National Index of Parish Registers, Vol 2, 1980, p 509

[10] Joyce Donald, The Letters of Thomas Hayton, Vicar of Long Crendon Buckinghamshire 1821-1887, Buckinghamshire Record Society, Vol 20, 1979, p. x.

[11] The term ‘Anabaptist’ originally meant ‘re-baptiser’. Those who joined the movement early had been baptised as infants but, convinced that this was not valid, were then re-baptised following a conscious decision and a profession of faith.

[12] Robert Baillie, 1646. Quoted by Andrew Bradstock, Radical Religion in Cromwell’s England, 2011, p1.