Some basic information could be pieced together from local directories and census entries together with the Reports of the BFSS published annually:

| BOYS | GIRLS | TOTAL | MASTER | MISTRESSS | SOURCE | |

| 1841 | Robjohns? | C | ||||

| 1842 | 50 | ? | ||||

| 1843 | 54 | 79 | 133 | |||

| 1844 | 83 | 74 | 157 | |||

| 1845 | ||||||

| 1846 | 87 | 79 | 166 | |||

| 1847 | Stedman | Robjohns | D | |||

| 1848 | ||||||

| 1849 | Greenfield | |||||

| 1850 | ||||||

| 1851 | 54 | 55 | 109 | Stedman | C | |

| 1852 | 51 | 52 | 103 | |||

| 1853 | 52 | 58 | 110 | Stedman | Greenfield | D |

| 1854 | 60 | 52 | 112 | Stedman | Greenfield | D |

| 1855 | 61 | 68 | 129 | |||

| 1856 | 59 | 71 | 130 | |||

| 1857 | ||||||

| 1858 | ||||||

| 1859 | 40 | 40 | 80 | Ainsworth | AR | |

| 1860 | 47 | 55 | 102 | |||

| 1861 | Kirby | Greenfield | C | |||

| 1862 | ||||||

| 1863 | ||||||

| 1864 | Witty | D | ||||

| 1865 | ||||||

| 1866 | ||||||

| 1867 | SOURCES: | C = census | ||||

| D = Directory | ||||||

| AR = Annual Reports | ||||||

It will be seen that enrolment figures climbed steadily in the 1840s and went upwards again in the 1850s although starting from the lower total of 109 in 1851. The information is too patchy to allow firm conclusions to be drawn, but numbers do not seem to have been so well maintained in 1859/1860.

The school was only sparingly mentioned in the local press. Unusually the annual report of 1855 was summarized in the Bucks Chronicle, 19 May, p 3, under the heading ‘Advantages of a British School’. Two masters are mentioned by name. Mr Stedman read a paper on the ‘Rise and Progress of the English Language’ to the Amersham Literary Institute (Bucks Herald, 19 January 1856, p 5). Mr Kirby spoke at an evening meeting following a public examination of the scholars at the British School at The Lee. Relating some of the many discouragements schoolteachers had to contend with ‘he urged the importance of parental co-operation with the master, and regular and early attendance. His experience showed him that those parents who neglected these duties were often the first to complain of the want of progress in their children’ (South Bucks Free Press 7 June 1862, p10). This will no doubt resonate with many teachers today, but the report also shows how the British Schools were very willing to have their achievements publicly assessed and how teachers would co-operate in examining each other’s pupils. On 31 July 1862 it was the turn of Mr Kirby’s boys, 32 of whom, described as ‘intelligent and respectable lads’ were examined in scripture, geography, spelling, mental arithmetic, writing, drawing and singing, which gives some idea of how they spent their time.

Perhaps it was on this occasion that the wonderful sketch by Master J Line aged 11 was put on display (https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/19th-century/the-line-family/). Mr Kirby must have valued it highly as it was eventually taken to America, presumably in one of the three items of luggage which accompanied the family when they crossed the Artlantic aboard the Wisconsin. For us it is a rare glimpse of the high standards which could be reached at the school.

The results obtained by the master, Mr HT Kirby, were praised, especially as ‘three years ago the school was in a very low state, but the perseverance and assiduity of Mr Kirby have raised it to great efficiency, as the examination proved. Mr Kirby bids fair to become as successful teacher in Amersham as ever E. West, Esq. has been. To the discredit of the town the attendance was very thin. A collection was made, which amounted to £1 7s [shillings] to give the children a treat.’ (South Bucks Free Press, 9 Aug 1862, p 2). This contrasted with the parents at The Lee whose attendance, at the evening meeting and also at the celebratory cake and tea served to the scholars after their ordeal ‘ showed the evident attachment of the people to the school, most of the parents with others having thrown up their work to be present, as they were at the tea also’.

The reports sent the BFSS which formed part of the published Annual Report show the school from a different perspective, that of the managing committee. Disappointingly the teachers are rarely named in them, but they do give some further glimpses of the schools’ development.

Some insight into the school’s finances has already been gained from Ebenezer West’ letter. The report for 1849 showed that over the previous eight years school fees had brought in £260 16 shillings and threepence while voluntary contributions had totalled £664, so that the school had raised over £900. The Committee was able to comment that ‘the aid rendered has been clogged by no conditions infringing on the rights of conscience or unfriendly to that spirit of independence which becomes free men.’[1]

The report for 1842 noted that they had 50 girls enrolled and that there had been a steady rise in applications since the public exam held at Christmas last. Keeping numbers up before schooling became compulsory was not easy and became much more difficult when the weather was bad. This affected prices and increased the cost of living, especially for families ‘ill able to forego the small earnings of the younger members of the family’ (1849). This was again a factor in 1854 and 1855 when the ‘unusual length and extreme severity of the winter’ again pushed food prices much higher, but this time attendance was less badly affected.

In 1856 the committee reported that their ‘chief matter of regret was that the children, especially the boys, leave school at so early an age’. In 1859 we are told that most leave aged 10 or 11. ‘If they could stop they would be fitted for higher places than they get now.’

The report for 1855 is of particular interest because the committee

‘believed it would be interesting to many to know what becomes of the children on leaving school; they accordingly requested the master and mistress to furnish them with tables of the present occupations, so far as they can be ascertained with tolerable accuracy, of the 100 boys and 100 girls who had most recently left the schools. The following is the result: — farmers, 6; trades — butchers, bakers, grocers, poulterers, etc, 22; mechanics — chairmakers, carpenters, shoemakers, etc, 34; domestic servants, 8; soldiers and sailors, 4; agricultural labourers, draymen, etc, 23; no employment, 3.

Of the 100 girls, it may suffice to say that 53 are in service, of whom 30 are in superior situations; 29 are dress or bonnet makers; 6 are married; and only 12 are at home with their parents. The education received in these schools has fitted these young people for their present position; in many instances it has enabled them to rise from a lower one to that which they now hold.’

This sense of mission, to help children rise in the world and to influence it for good, had already been vehemently described in the 1851 report:

‘During the last five years 162 new scholars have been admitted and 155 old ones have left. How shall we estimate what has been thus accomplished in the formation of good habits, as well as in the calling out of latent powers? By the education these young persons have received they are better qualified for taking their part in the great battle of life, and for doing good service for God and man: nor must it be supposed that this is all; the competition to which other schools have been exposed has improved them so that the general standard of instruction is far higher than it was in this neighbourhood twenty or even fifteen years ago.’[2]

All but one child of the 109 on roll had previously attended a different school. They could also rejoice to see on the subscription list an increasing number of parents and old scholars.

The same report gives us a glimpse of the curriculum.

‘All receive instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic; 71 are taught grammar, 77 geography, 27 singing by notes; 18 boys learn drawing and 2 have begun mensuration.’

Back in 1844 the committee had inaugurated tuition in mechanical and object drawing, which was deemed a useful skill for future artisans and in 1849 the boys were learning ‘fractional and decimal arithmetic, measurements of surfaces and solids’. Some of the older boys were also being taught in 1855 the elements of agricultural chemistry, presumably by Mr Stedman.

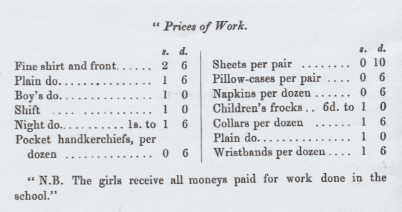

Sewing and knitting was taught extensively to the girls. They made and mended articles to help their parents and much of their work was sold. This income helped to defray the cost of their education as well as to fit them for future trades and for caring for their families. The amount raised is frequently mentioned in the reports. In 1856 they earned £12 3 shillings and sixpence which was two-thirds of what they would otherwise have had to pay in school fees. Some also earned money as monitors, £2 16 shillings being paid out that year.

This was a very practical way of encouraging the education of girls.

It was also in 1846 that a school lending library was established, the cost having been met by ‘a few friends’. This was open to past as well as current pupils and membership went up to 60 within a month of its opening. This may have been bought as a collection for amongst the items offered for sale in the Borough Road catalogue was a ‘Library of Sixty Volumes on Historical and Scientific Subjects, Natural History, Voyages, &c, 18mo, bound in sheep. An excellent foundation for a School Library….Retail price £2, Reduced price £1 15 shillings.’

The committee would have liked children to have much greater access to books at home and estimated in 1852 that the extra cost would only amount to a halfpenny per child per week.

[1] The expression Free Churchmen, instead of Dissenters or Nonconformists, was increasingly used at this time by those who were not part of the Established Church.

[2] Some so-called schools offered little more than child-minding or might concentrate on passing on practical skills such as lace-making. Of 13,879 returns sent in for the 1851 Education Census from schools classified as ‘Inferior’, in which only reading and perhaps writing was taught, no fewer than 708 bore a mark because the teacher was apparently unable to sign! Mann added ‘the same is true of 35 Public Schools, most of which had small endowments’, Census of Great Britain 1851, Education in Great Britain. Being the Official Report of Horace Mann, of Lincoln’s Inn, Esq., Barrister-at-Law, to George Graham, Esq., Registrar-General, London, 1854, p29