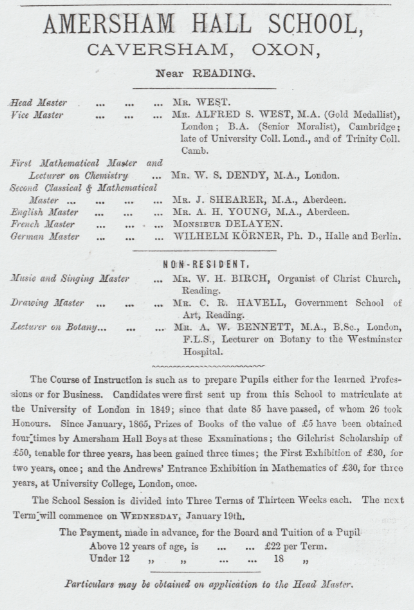

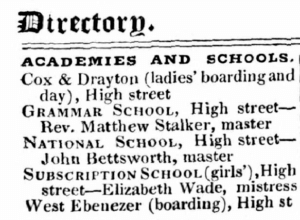

Pigot’s Directory for 1842 shows that Amersham already had six schools in operation, all in the High Street — Cox & Drayton’s ladies’ boarding and day school; the Grammar School founded in 1621, then under the Reverend Matthew Stalker; a school for teaching writing and arithmetic founded in 1728; the National School whose master was John Bettesworth; a girls’ subscription school run by Elizabeth Wade; plus a boarding school, Amersham Academy, run by Ebenezer West.[1] By 1841 this school had 39 pupils and the census lists 28 boarders there ranging in age from 7 to 15. Two assistant masters are employed. The school moved to Caversham in 1861.

by kind permission of the Librarian of the Society of Genealogists)

Eliza Cox and Ann Drayton provided boarding for twelve girls aged 6 to 15 and had a resident assistant. Only one Elizabeth Wade appears in the 1841 census. Aged 46 she is part of the household of Joshua Wade, a gardener. No occupation is given for her. The 1851 census finds them in Church Street as man and wife with a daughter aged 25, but again no mention is made of a school.

The Rev Matthew Stalker was born in Cumberland, at Castle Sowerby in about 1773 according to the 1851 census. After being made Deacon and assistant Curate of Hesketh Forest on 29 June 1800 he was ordained priest about a year later, on 14 June 1801. The records show him as the stipendiary curate of Chesham Bois 26 June 1815, with an annual stipend of £40 and the use of a house, but it seems he was there much earlier as he married Sophia Bovingdon, a widow, at Chesham Bois on 1 September 1808 by licence. By 1823 his stipend had been increased to £60.[2] He was headmaster of Dr Challoner’s Grammar School from 1826 to1849. FR Treadgold[3] notes that although his time in office began well, the teaching suffered after the death of his son who ‘assisted his father and taught the children mensuration[4] and the practical branches of mathematics, in addition to the common education.’ This must have been his eldest son Robinson Stalker who was buried at Chesham Bois on 20 September 1830. Such was the parlous state of health of Matthew Stalker by 1849 that he was persuaded to resign and his successors, the Rev S Newman and the Rev EJ Luce, both agreed to pay him a pension. He died in 1852 and his wife in 1854.

Not all these schools were teaching the same curriculum. The original purpose of a Grammar School was to teach Latin grammar, at a time when Latin was the key to all learning and also functioned as an international language facilitating the exchange of knowledge between people of many different mother-tongues. Although ‘any Parishioners have a right to send their Children to this School; which is solely for Greek and Latin’, the school seems to have had no pupils at all in 1780 or in 1818.[5] Reports made on the school in 1832 and 1864[6] shed some light on the teaching there. Instruction in Latin was free. Some boys were taught Maths and English, either by the master in return for a fee, or by attending the Writing School in the gap between morning and afternoon classes which ran from 8.30 to 11 and 3-5.[7] In 1864 all 17 boys were learning Latin, 4 Greek and 5 or 6 French. Up to six books of Euclid[8] might be taught. In Geography they did ‘fairly’, but ‘the arithmetic of the remaining boys was scarcely satisfactory’.

There was little interchange between the schools according to a report in 1864: ‘There are a National and a British school in the place; some boys pass to the grammar school from the former, but none, as I was told, from the latter, though the master readily exempts from the Catechism[9] at the desire of parents.’

The Grammar School had declined until its premises were taken over by Lord Cheyne’s Writing School which according to Treadgold (p 47) in 1840 had over 40 pupils each paying a penny a week.

In addition a school run by Mary Ainsworth and her husband Henry in the High Street can be found in the census but is not mentioned in the Directory. Four boys and one girl were boarding there, ranging in age from 4 to 8.

Two schoolmistresses are listed by the enumerator without specifying where they were working, Mary Harding, 23, was lodging in Whielden Street with Mrs Hoare, a laundress, and her family. Mary Robjohns’s landlady was Ann Toms in the High Street. No occupation is given for Mary, possibly because (like Elizabeth Wade) she was not the head of the household, but she is known to have taught at the British School and may already have been doing so.[10]

This is still not the full picture as one educational provider had no need to advertise: Amersham workhouse ran its own schools until the late 1870s. In 1854 John Robinson Bettesworth was schoolmaster there and Miss Elizabeth A Eaton was teaching the girls. In the 1861 census only the schoolmaster is listed, Samuel Bryan, but by 1864 Miss Gillett had joined him.

[1] For more details of West’s career and of his school see https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/19th-century/martha-morris/ and https://amershammuseum.org/history/research/other-articles/the-academy/ A man of wide-ranging interests, West found time to translate from German KF Peschel’s influential Elements of Physics, finishing his introduction to the second volume in Amersham on 14 July 1846. This is still being reprinted.

[2] See https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/, person ID 6351

[3] The Story of Dr Challoner’s Grammar School Amersham, 1974, pp 45-48

[4] A branch of practical geometry concerned with calculating lengths, areas and volume

[5] Nicholas Carlisle, a Concise Description of the Endowed Grammar Schools in England, Vol 1, 1818, p 44 and The Literary Panorama and National Register, Vol 2, 1807, col 248

[6] The 1832 report stemmed from the nationwide Inquiry Concerning Charities. The 1864 report formed part of the Schools Enquiry Commission (also known as the Taunton Commission) and was published in Vol XII, 1868, pp 175-176

[7] FR Treadgold, The Story of Dr Challoner’s Grammar School Amersham, 1974, p 45. For the Report made in 1864 see Appendix 2.

[8] Euclid’s 13 books were concerned with number theory and a series of increasingly sophisticated theorems and two- and three-dimensional geometry.

[9] The catechism was included in the Book of Common Prayer and sub-titled: ‘An instruction to be learned of every person before he be brought to be confirmed by the Bishop.’ It covered the main points of doctrine in the form of questions and answers. The creed and the ten commandments were also included.

[10] For more detail see Section 6 ‘Schoolmistresses’.