Mary Robjohns (1813-1900)

Mary was probably the first teacher appointed by the Amersham Committee. She had been baptised on 14 November 1813 at Milton Abbot parish church in Devon, the daughter of Amy and Henry Robjohns, who was a miller or millwright at Combe Mills.

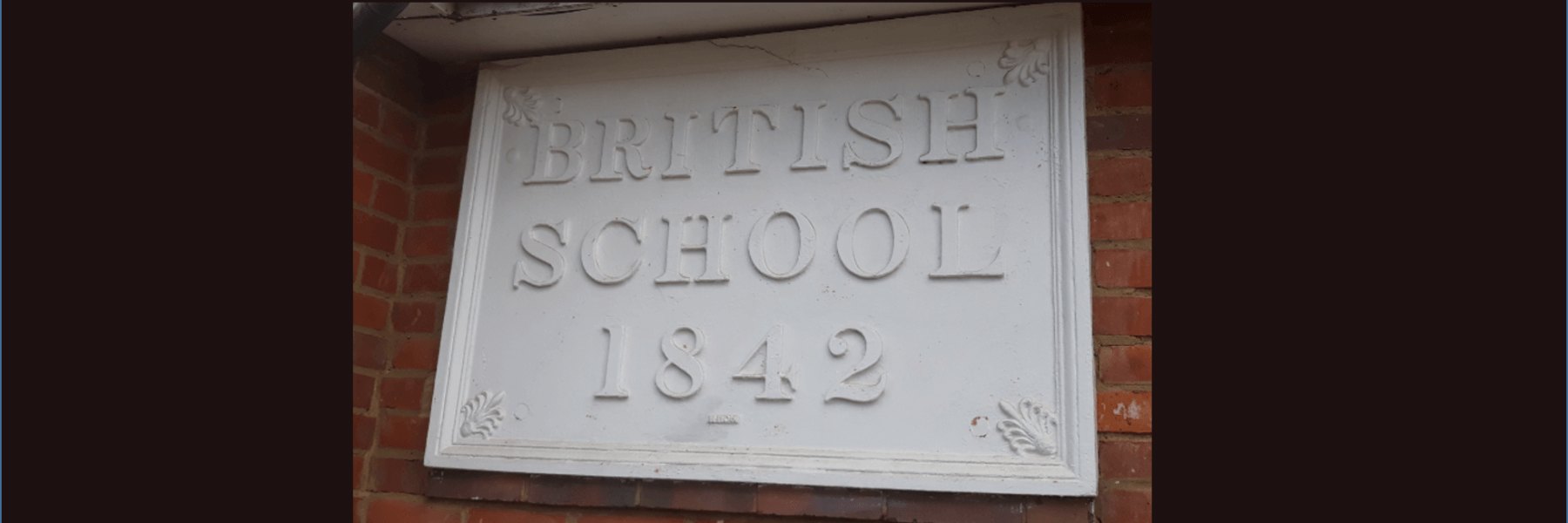

In June 1840 she applied to be a student at Borough Road College in Southwark which trained many teachers for the British Schools. Her testimonials, conserved in the BFSS Archive at Brunel University, reveal that she had been ‘instructed’ [been a pupil?] at Tavistock Girls School and had later worked in the British School in the parish of Mary Tavy under the direction of Mr Smith before superintending the school at Maybury. Mrs Rooker stated that she had ‘maintained a pious and consistent profession’. By 1841 she was in Amersham, lodging with Ann Toms in the High Street. No occupation is given for her. The 1847 Directory listed her as schoolmistress at the British School.

The List of Members of the Lower Baptist Church recorded two dismissals of Mary Robjohns, one in 1842 and one in 1850. Despite that, she is still to be found in the 1851 census lodging in Union Street with John and Charlotte Plester. Aged 37, she was described as a daily governess.

Ten years later she was back in Devon living with her sister and working as a schoolmistress. They had a servant and a boarder, 13 year-old Emily Gregory, living with them.

In 1871 she was still in West Street, Tavistock, and mistress of a private school. Aged 67 in the 1881 census she has retired and was again living with her sister Anna, but now at Cross Cottage, Kilkhampton, Cornwall. She died on 5 August 1900 and was buried in the Wesleyan Cemetery there.

Mary Jane Greenfield (1828-1907)

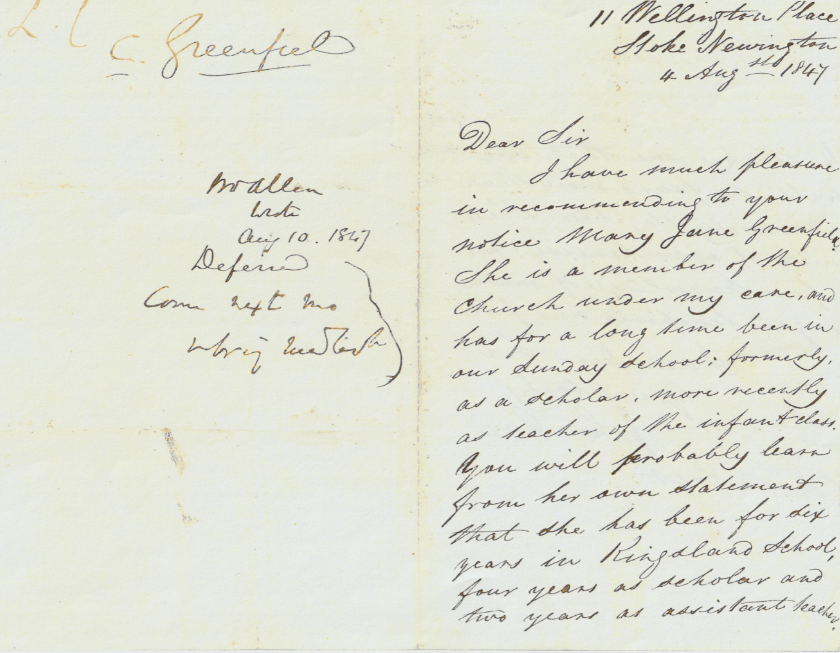

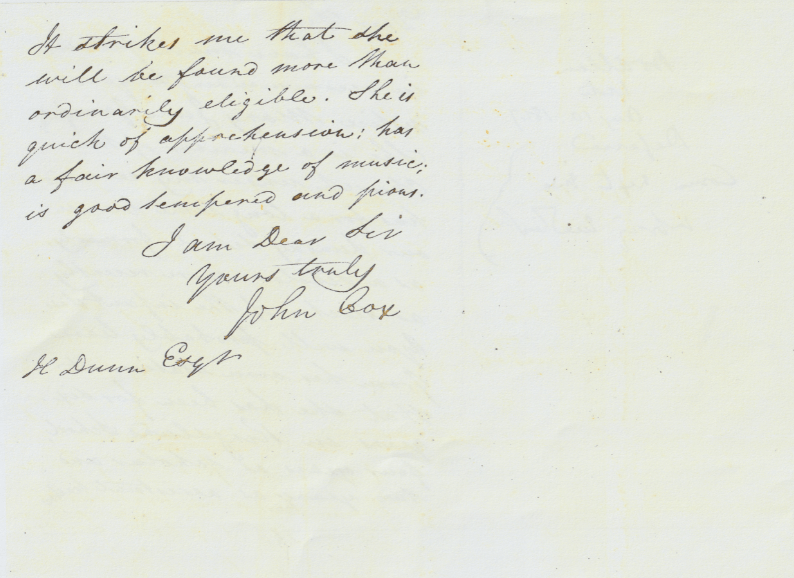

Mary Jane was baptised on 27 June 1828 at Shoreditch St Leonard, the daughter of Mary and William Greenfield, a plasterer of Union Street. In September 1847, aged 19, she also applied for admission to the Borough Road College and from her testimonials we can gain some information about her early life. She had been at the Kingsland British School for four years as a scholar, followed by two years as assistant teacher. Mrs Blythman, the schoolmistress there, was able to say that her conduct had been most excellent and that she had an aptitude for teaching. To add to her experience she had been a Sunday School teacher for four years. She had the forethought to supply a reference from a surgeon who said that she was never ill and that her general health was very good. When she was concerned that her application had gone astray John Cox wrote on her behalf to the College and commented: ‘It strikes me that she will be found more than ordinarily eligible. She is quick of apprehension, has a fair knowledge of music; is good tempered and pious.’ The annotation on the letter suggests that the matter of her admission had been deferred to the next committee meeting the following month.

In 1851 Mary Jane, aged 22, was living next door to Mary Robjohns and lodging with Ann Potter, a widow, and her daughter Sophia in Union Street, Amersham. Her occupation is given fully as ‘schoolmistress at the British School’. Ten years later nothing had changed. She had the same job, the same landlady and the same address. Perhaps she and her landlady sometimes compared notes about Mary’s upbringing in Hackney and Mrs Potter’s in the city of London.

It seems that the hopes John Cox and others had for her were realised. The Annual Report for 1856 contained a real tribute ‘Of the girls’ school it is needless to say more than that it maintains the high standard it long since reached’ and in 1859 ‘It is scarcely necessary for them to repeat the assurance of their confidence in Miss Greenfield’s management, now that she has filled the post of mistress for almost eleven years.’ This suggests that she arrived in 1847/8 fresh from training and took over from Miss Robjohns.

The Cocks family also seem to have thought highly of her and to have valued her influence on their daughter Jemima who also became a teacher and moved to a school in Bourton. John Cocks wrote to George and Hephzibah Youatt in London on 10 Dec 1849: ‘We heard from Jemima last week, she seems to succeed in the school they numbered 40 when she went and now they have 81 she improves in writing and diction. The instruction she received from Miss Greenfield was of great service to her and I don’t doubt but she will become an efficient teacher.’ See https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/19th-century/john-cocks/

By 1871 Mary Jane had moved back into London and rejoined her family. Most probably it was the closure of the Amersham school to which she had given many years of service which prompted the move. She went to live at Johns Cottage, Oakfield Road, Hackney, with her brother, father, sister-in-law and nephew. One reason for this may lie in her younger brother Philip’s job. He, too, is a teacher and may have helped to find her a post.

She is still part of his household in 1881, in Avenue Road, Hackney, but her job description has changed to ‘governess’. In 1891 little has changed, except that her brother has died. The 1901 census throws up some anomalies. Philip H Greenfield has an aunt Mary living in his household at 12 Barclay Place Terrace, Lea Valley Road, Leyton, West Ham, and she is working as a governess. Her second initial was written as ‘M’ not ‘J’ and her age given as 65, rather than 72. Many other governesses at this time, if still in need of a job, would knock years off their real age to increase their chances of employment.

The rapid advances in the education of girls after 1870, something for which both Miss Robjohns and Miss Greenfield had helped to lay the foundations, may have made it harder for them to find work in their last years, as girls’ schools started to benefit from the increasing availability of women graduates. They both had the benefit a formal training plus experience of teaching in schools, and evidently found jobs at a time when many elderly governesses, who lacked any qualifications, were struggling to find work.

A probable death is recorded in 1907 for a Mary Jane Greenfield in the Registration District of Rochford, aged 79. She had remained single and worked into old age, still managing to find work as a governess rather than continuing in her first kind of post as a school-teacher. It is clear that she was a mainstay of the Amersham girls’ school and probably its longest-serving teacher, influencing many lives.

SCHOOLMASTERS

Stephen Stedman (1820-1882)

Stephen Stedman is named in local directories as master at the British School in 1847, 1851 and 1857.

It is unlikely that he was the first man appointed as the Annual Report for 1847 notes that ‘the unavoidable change of masters has, of course, been injurious to the boys’ school…..from the diligent and zealous exertions of the present teacher they expect the number of scholars will be greatly increased.’

Stephen Stedman was born on 29 December 1820 and baptised at Limpsfield in Surrey, the son of Susannah and Dan Stedman. His father was a painter. In later life he seems to have preferred the name Stephen Ashton Stedman.

On 19 December 1843 he married Jane Stanford at Croydon, at the Parish Church of St John and at that time was already a schoolmaster. His name does not appear in the Transcript of the List of Male Students at Borough Road College 1810-1916.[1]

Details from the 1851 census show the couple living in the High Street, Amersham. Their first child Sarah, 6, had been born in Uckfield, Sussex, in the third quarter of 1844. This is also Jane’s birthplace and may simply mean that she had returned home for the birth of her first child.

The birth of Fanny Jane in Amersham in the last quarter of 1847 was followed by that of Frederick William in 1853, Allen Bertie in 1854 and Ellen Mary in 1856. Stephen and Jane seem to have been of the Baptist faith as the list of members in the Minute Book notes ‘Stephen A Stedman and Jane dismissed to the church at Lockwood nr Huddersfield June 1857’. Although Stephen himself had been baptised it is likely that he refrained from ‘infant sprinkling’ as the Baptists liked to call it. Frederick William’s baptism was not recorded until 5 November 1876 in Dugshai, Bengal, India, where his date of birth was noted as 16 February 1853. He served with the army and may have been posted to Bengal.

Their next child, Frank Forrester, died as an infant and was buried at Lockwoood Baptist Chapel. Charles Ernest was also born in the Huddersfield area in 1860. Annie Phillis completed the family in 1862 after a further move to Walsingham in Norfolk. She died aged 20.

In 1861 and 1871 Stephen and Jane can be found at separate addresses. In 1861 he was a visitor staying in a house right next to the Baptist Chapel on Buxton Road in Lockwood, while Jane and the six surviving children were at Cartworth, Hinchliff Hill, Holmfirth.

In 1871 they were both in Wymondham, but while Stephen was staying in an inn in Chandlers Hill (presumably in company with another schoolmaster Thomas Bradbury who is listed there), Jane was at home with her children Bertie, Annie, Ellen and Charles. Ann Bradbury, 48, and Mary, 23, were also with them, so perhaps the men were staying at the inn to ease overcrowding.

An entry in Kelly’s Norfolk Directory for 1879 lists Stephen at the Grammar School in New Walsingham and he was also on the electoral rolls for Heath, Fakenham, as the occupier of a house and garden. Aged 60 he was still working and at the same address, according to the census. As well as Jane, Bertie, Phillis and a grandson called Edwin were enumerated there.

On 2 December 1882, however, the Lowestoft Journal carried the announcement of his death at Fakenham on 27 November, describing him as ‘late of Heathersett and Wymondham’.

Henry Ainsworth (1800-1859)

No trace of Henry Ainsworth had been found in directory entries, newspapers or the census linking him to the British School. It is only because he was, most unusually, mentioned in two consecutive Annual Reports that his story could be pieced together.

Stephen Stedman had left in June 1857. The 1859 Report makes clear that ‘when the committee learned of the serious nature of Mr Ainsworth’s illness they engaged a qualified teacher from the Normal School’. The following year they recalled that the boys’ school ‘had laboured under considerable disadvantages, arising from the failing health of Mr Ainsworth, and the unavoidable change of masters that followed his death’. Thus he was probably in post for a little under two years in between the appointments of Mr Stedman and Mr Kirby.

It was by no means certain that Mr Ainsworth would have remained in the Amersham area up to the moment of his death, but investigations started with a possible death recorded in the Amersham Registration District for a Henry Ainsworth aged 58 in the first quarter of 1859 and a further check showed that a Henry Ainsworth applied to enter the Borough Road College in 1844.

The 1841 census shows Henry Ainsworth living with his wife Mary in the High Street. His profession was given as ‘schoolmaster’. In the house were three boys whose ages were rounded down to 10 and a brother and sister aged 4 and 6, so it looks very much as though the couple are running their own school and these are pupils who are boarding. Henry could not have been teaching at the boys’ British School, which would not open for another five months.

This couple are very likely to have been the Henry Ainsworth and Mary Stratford already mentioned as the first people ever to be married in the Lower Baptist Chapel. There is a probable death entry for Mary in 1849. The Minute book implies strongly that burials were still taking place in the Baptist burial ground, but the records of interments after 1840 have never been located. No children were born between 1837 and 1849 to Ainsworth/Stratford parents, which might have conclusively identified this couple as the ones who got married in 1837.

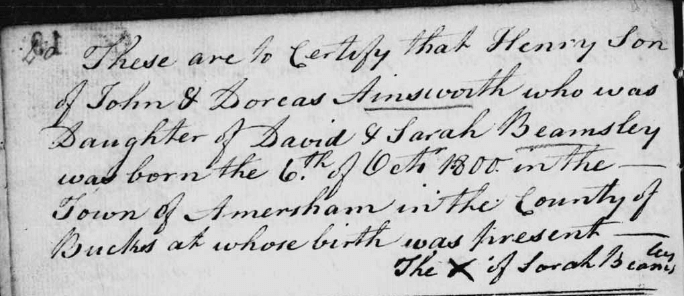

In 1851 Henry, born in Amersham, was staying with a family called Pridmore in Easton, Northamptonshire. The Pridmores have no apparent link with Amersham. His age is given as 40, rather than 50, and he is a ‘Professor of English Language.’ Once his birth was linked to Amersham one birth entry stood out amongst the records of the Lower Baptist Chapel:

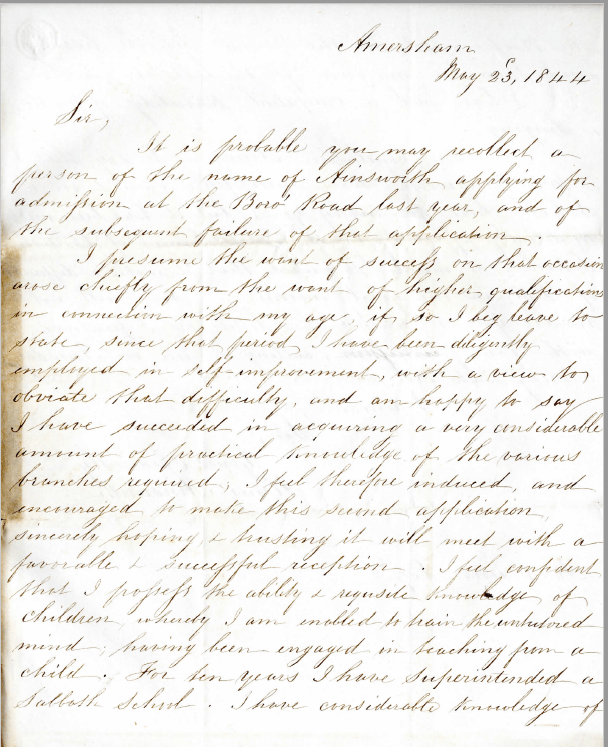

The few clues gathered were stitched together, with added detail from the letters written by Henry’s referees when he applied to Borough Road College. He applied twice, having been turned down the first time on the grounds of age, as he was then 40.

From his own letters of application (dated 30 June 1843 and 23 May 1844) and from his referees emerges a picture of a man who is largely self-taught. Now a member of the Wesleyan congregation, he has instructed in Sunday Schools for over 20 years and taught in a boarding and day school kept by his wife for the past six years. They have no children. In the first letter he writes:

‘With respect to attainments I trust I may be allowed to say that my knowledge is not superficial, it having cost me much labour to acquire it, as I am nearly self-taught. I am perfect in the first four rules of arithmetic and have some acquaintance with the others in advance. I have also to a certain extent some knowledge of Grammar, Geography, History, &c, &c.

I beg leave to say that I shall not be able to devote more than six months to study.’

This was a realistic time-frame, as at that time the College’s junior and senior classes ran for three months each and many students completed only the first class.[2] One of the headmasters under whom FH Spencer worked, George Webb of Woolwich, had had three months’ training at Borough Road ‘sometime in the 1840s’.[3]

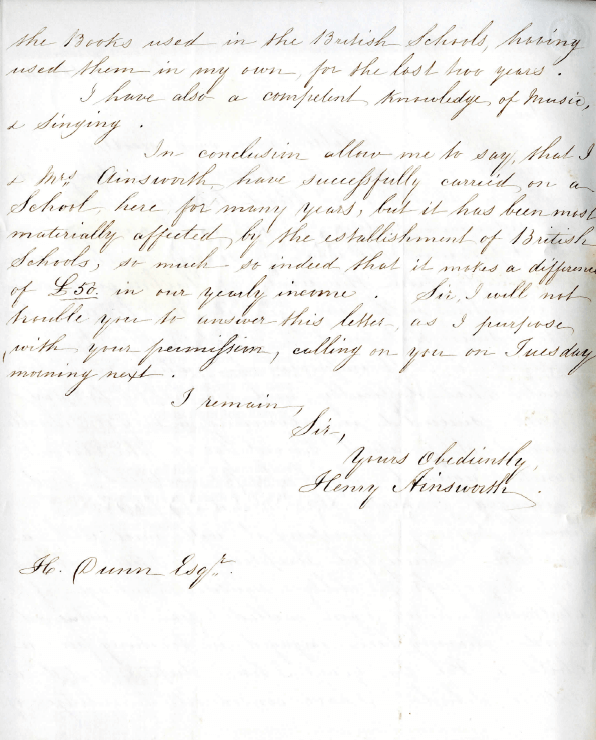

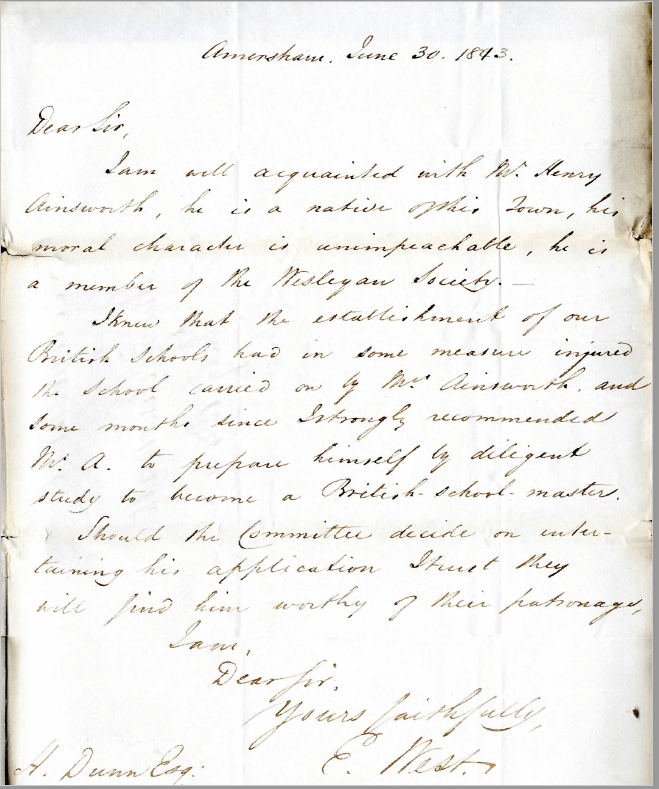

While very willing to update his qualifications it is clear that, for financial reasons, he can only undertake to do this for a limited time. Support came from John Coates, a Wesleyan Minister, and from Thomas Nathaniel Gray, a local surgeon, who mentioned his ‘activity and energy’ and stated that his health was ‘unexceptionally good’. A key supporter must have been Ebenezer West, urging both Ainsworth to apply to the College and Henry Dunn to accept him.

Ebenezer West wrote to Henry Dunn on 30 June 1843 and 22 May 1844. Knowing that the opening of the British School had meant that it had become much more difficult for the Ainsworths to attract pupils to their school, West had advised him ‘to prepare himself by diligent study to become a British-school-master’ and that advice had been followed in the intervening eleven months.

It is not at all clear what Henry Ainsworth did following his training at the Borough Road College in 1844. His wife’s death took place in Amersham in 1849 and in 1851 he was with a family in Northamptonshire, whether in connection with a job or not we cannot tell.

He must have been appointed to the British School in Amersham after Stephen Stedman’s departure in June 1857 and continued in post until 1859. The Annual Reports refer to a new master being appointed only after his death.

The job was an exacting one for a man in full health and he must have struggled to cope. The normal school hours were 9 to12 and 2 to 4 or 4.30. During this time, as the sole adult, he would have had to control 50 or so boys aged around 4 to 13, and manage lessons of all standards, all taking place within one room. While monitors or pupil teachers may have been doing a proportion of the teaching, Mr Ainsworth would still have been responsible for briefing them, supervising them and checking on how well the lesson had been absorbed. If pupil teachers were under training, it was customary for them to have secondary-level instruction from as early as 7 in the morning and once again different levels of attainment might have to be catered for. In many places the teacher would also hold evening classes for those who had not had the chance of an elementary education, and even take part in the Sunday School as well.

As a young man of 24 [therefore in about 1896] WH Spencer found his work-load a heavy one:

‘besides teaching a little French, and some elementary mathematics to the top VIIth and Ex.VIIth class, which, as I was supposed to be the “young intellectual” of the staff, was mine more often than not, I taught everything to them and to lower classes during my short service in the middle of the school. This meant arithmetic and English (grammar, composition, reading, dictation, spelling — all still regarded as separate subjects), geography and history, drill (still the only form of physical education, though it developed into barrack-yard physical jerks of a long-discarded type), science, with experiments which by no means always succeeded, and drawing (done in my later years at this school with coloured chalks on sheets of brown paper), Scripture, singing (though I never really attained facility with tonic sol-fa, which was the accomplishment of most of my colleagues) — everything, in fact. It was gruelling work in the middle school, with fifty to sixty boys of all ranges of ability.’[4]

Mr Ainsworth’s labours came to an end on 27 March 1859 and the Bucks Chronicle carried a death notice on 13 April 1859, p 3. He died at his home in the High Street, attended by Sarah Syrett of Church Alley. He had been suffering from pneumonia for 14 days and had heart disease which had been brought on by contracting rheumatic fever two years earlier. This must have been what had affected his general health and energy and left him struggling to run the school. It was a sad end to the endeavours of a determined man.

Henry Thomas Kirby (1835-1917)

Henry is virtually certain to have been Mr Ainsworth’s successor. Immediately after mentioning Ainsworth’s death, the annual report goes on to say ‘Under Mr Kirby, good order is maintained, and the teaching is conducted with due energy: the progress of the boys is creditable to him and to them: the improvement is especially marked in their writing.’ He was apparently appointed from or at least obtained via a ‘Normal School’. This was a common title for a teacher training college. A Henry Kirby did apply to Borough Road College in 1838 from Benson in Oxfordshire, but this cannot be the same person, so it appears that Henry Thomas Kirby had obtained his training elsewhere.

Like Henry Ainsworth he was a local man. Born on 5 May 1835 he was baptised at Chalfont St Giles on 8 May 1836, the son of Ann and Joseph Kirby of Frog Hall, a brickmaker. In the 1851 census Henry was listed as a brickmaker aged 15. His father employed 8 men and an older brother Edward was already following in father’s footsteps.

In 1861 Henry was still living with his parents at Frog Hall, near Chalfont St Giles, but has changed his job and is now a schoolmaster. As he took over from Mr Ainsworth, this implies that he is at the British School. He does not appear to have trained at the Borough Road College but it is clear that he was very successful in this job and was highly regarded, so it is a surprise to find that by 1871 he had left teaching and was the local postmaster in Chalfont St Giles.

Other circumstances had also changed. He was a widower with three sons — Herbert Henry, born 1867, Frederic Charles (1869) and Arthur Lorne, who was less than a month old. This suggests that the child’s mother died in or soon after childbirth. The mother’s surname, recorded when the births were registered, was Goodman. Ann Goodman and Henry married in the second quarter of 1865. Her age on death was 31 which allows her to be identified as the daughter of William and Elizabeth Goodman. Her father was a grocer who was also farming 72 acres at Chalfont St Giles in 1861 and employed 8 men and 5 boys.

As Benjamin Witty was listed as master of the British School in the 1864 Directory, Henry Kirby must have left that teaching post before he got married, rather than as a result of doing so.

With three small boys to look after and their living to earn, it is not surprising that Henry married again quite soon, in the third quarter of 1872. His second bride was Emma Susanna Potts née Teesdale. The couple went on to have other children. By 1881 the family is still in Chalfont St Giles where they have a grocery store. With them are Frederic Teesdale Kirby aged 3 and Henry George, 1. An older daughter Lilian Frances, 7, is staying with relatives in London as is her older half-brother, Arthur Lorne Kirby, now 10. Another son of the first marriage, Frederic Charles, died aged 4.

Soon after this the family must have taken the decision to emigrate. They sailed from Liverpool aboard the 2,386-ton SS Wisconsin and landed in New York on 11 December 1883. They took with them three pieces of luggage containing whatever they had chosen with which to start their new life. It is remarkable that Henry managed to include mementoes of his time at the British School, including the mounted sketch by Master J Line which was eventually returned to Amersham by one of his descendants (https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/19th-century/the-line-family/). Henry appears on the passenger manifest as a farmer, which may show what his intentions were for the new phase of his life. At this point the parents were aged 48 and 45 and had with them Herbert Henry, 16, Arthur, 11, Lilian, 9, Frederic, 6, and Harry, 4 (New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957, M237/472). When another census was taken at Junction City, Kansas, on 1 March 1885, Henry’s occupation had changed again to carpenter.

By 1910 the children had all left home and Henry was a book-keeper. He died on 21 Jan 1917 and a short obituary was published in the Junction City Republic on 25 January, p 1, column 2 which fills in some of the gaps for us:

‘HT Kirby was born in Buckinghamshire, England, in June, 1835, and lived there until coming to Kansas, working first with his father, who operated large brick yards, later teaching in a private school, and taking over a country store, which he ran for some years. He was twice married, his second wife and five children accompanying him to America, reaching Junction City in December 1883. Up until the time that failing health forced his retirement, he was employed in the collection department of the Central National Bank for over twenty years, always faithful, always at his desk, he had become one of the features in the business of the city.’

Emma died later the same year, their shared gravestone in Junction City’s Highland Cemetery giving her dates as 18 Oct 1837 – 27 June 1917.[5]

A highly successful teacher, he showed great versatility in pursuing so many other occupations.

Benjamin Witty (c1835-1875)

Benjamin Witty is the last known schoolmaster to have served the Amersham British School. He is listed in a Directory for 1864 and probably took over from Henry Kirby. He is unusual in being a second-generation master in a British School.

When he was a child his father, Matthew Cape Witty, who had been born in Cottingham, Yorkshire, was master at the British School in Stratford, Essex. By 1851 the family had moved to 22 Chapel Street, West Ham, and Benjamin, aged 15, was already a pupil teacher. Unlike his father Matthew, Benjamin did not attend the Borough Road College, but he was clearly beginning the training which would lead him into a similar career.

He married in the first quarter of 1855 Alice Brown in the West Ham Registration District, but by 1861 they had moved to New Road, Battersea, Wandsworth. They are living at St George’s School and Benjamin has become a National schoolmaster. They already have three children – Alice Elizabeth (b 1855), Benjamin (b c1857) and Eliza (Elizabeth Hephzibah b 1859). Benjamin’s birthplace is noted as Stanford, Essex, and Eliza’s as Battersea, so presumably the family’s move took place between 1857 and 1859. Living in the same house are Charles Brown, an engineer born c1789, and Elizabeth, 59, who may be his wife and Alice’s mother. She is working as a housekeeper.

In 1861 Benjamin was 27. He had a wife, three children and a steady job. It may have seemed as though the course of his life was fairly well mapped out, but the following year his wife Alice died, aged only 26.

Benjamin next appeared in 1864 as the British schoolmaster in Amersham. In the first quarter of the year he married Elizabeth Statham who was four years his senior and in 1865 they had a son born in Amersham and named Ebenezer John Statham Witty. Statham is a name closely associated with Amersham,[6] yet the 1871 census showed Elizabeth to have been born in Stepney.

An Elizabeth Statham, daughter of Mary Ann and Joseph Statham, a butcher, was baptised at St Dunstan’s, Stepney, on 15 July 1832. By 1841 the large family had moved back to Amersham and Joseph was working as a baker in the High Street, as he was ten years later. By 1861, he had been widowed, had become a corn dealer living in the Market Square and his large household had been winnowed down to three — himself, his daughter Elizabeth, then working as a dressmaker, and the youngest child Alfred, 8, who was still at school. If Alfred went to the British School, that might have constituted the link between Benjamin and Elizabeth, but they could have met easily enough in a town the size of Amersham.

Although the name of their child at first glance might echo that of Ebenezer West, it seems that Benjamin Witty arrived in Amersham only after West had left it. He did have a sibling, Ebenezer Matthew Witty, who was born when he was about five and died a year later, so the name may have been chosen to commemorate him.

It is not certain when or why Benjamin Witty decided to move on, or whether his move helped to precipitate the school’s closure, but John Toovey’s desperate plea for a replacement teacher was dated 3 May 1866. The 1868 Post Office Directory for Warwickshire (p 1104) finds a Benjamin Witty at the Pestalalozzian Day School for Boys and Girls in Little Church Street, Rugby, which implies that he was probably there by 1867.

By 1871 he had returned to his father’s county of birth and was living in the School House at Bracewell near Skipton. In this census he is described as schoolmaster and professor of music. His wife was continuing to make dresses and Ebenezer was six. The children of his previous marriage seem to have remained in London. His talent for music may have been transmitted to his son Benjamin who declared his occupation as ‘musician’ when he married Mary Enderby in 1894 but seems to have earned his living later as a painter’s mate, probably working for a railway company.

In 1875, aged only 39, Benjamin Witty died.

His widow, with their son, moved to Bradford, and lived on until 1921, dying at the age of 89. John Statham Witty (having dropped his first name Ebenezer) became a teacher and composer of music and died in 1927.

These brief biographical details of the six known teachers at the Amersham British Schools bring to light some differences and some similarities. They were typical in being the sons and daughters of self-employed skilled tradesmen. Henry Robjohns was a miller, William Greenfield a plasterer, Dan Stedman a painter and Joseph Kirby a brick-maker. Only Benjamin Witty descended from a school-teacher while, at the other end of the scale, Henry Ainsworth’s education seems to have depended on his own efforts and to have been acquired later in life.

Three of the teachers (Miss Robjohns, Miss Greenfield and Henry Ainsworth) had been trained at the Borough Road College, the two women having previously served as pupil-teachers.

The same three, plus Stephen Stedman, are mentioned in the records of the Lower Baptist Chapel and probably attended the meetings there even though all of them were baptized in an Anglican Church.

In the 25 or so years of the schools’ history, the girls had only two teachers, the boys at least four, probably five. This may reflect the fact that there were many more employment opportunities for a literate male than for a female of equal ability, so the men were more likely to move on or change their occupation. Schoolmasters also could marry and have children of their own without having to choose between their family and their job. The higher salaries paid to men may reflect both these differences but could occasionally work to the advantage of a woman as she was cheaper to employ. Pamela Horn notes that ‘in 1870, while a certificated female earned, on average, about £58 a year, her male counterpart could expect to receive about £94.’ She also lists the most common, and usually lower-paid, alternatives: domestic service, factory work or dressmaking.[7]

[1] https://www.brunel.ac.uk/about/Archives/BFSS/Transcripts

[2] Stockwell College, BFSS Archives Info Sheet no 3, Feb 2012, p 2

[3] FH Spencer, An Inspector’s Testament, 1938, p166. A George Webb entered the College in 1846. See Transcript of the List of Male Students at Borough Road College 1810-1916 at https://www.brunel.ac.uk/about/Archives/BFSS/Transcripts

[4] FH Spencer, An Inspector’s Testament, 1938, pp191-192

[5] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90457816

[6] See https://amershammuseum.org/history/old-town/high-street-south/baptist-chapel/ for a pen used by a member of the Statham family in the British School in 1853.

[7] Pamela Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 1989, p 167. This disparity in pay was still very evident in 1900 when Emmeline Pankhurst became a member of the Manchester School Board. What she discovered fuelled her determination to increase the influence of women in public life. ‘Men teachers received much higher salaries than the women, although many of the women, in addition to their regular class work, had to teach sewing and domestic science into the bargain…..In spite of this added burden, and in spite of the lower salaries received, I found that the women cared a great deal more about their work, and a great deal more about the children than the men. It was a winter when there was a great deal of poverty and unemployment in Manchester. I found that the women teachers were spending their slender salaries to provide regular dinners for destitute children and were giving up their time to waiting on them and seeing that they were nourished. They said to me, quite simply: “You see, the little things are too badly off to study their lessons. We have to feed them before we can teach them”,’ Emmeline Pankhurst, My Own Story, 2016, p35.