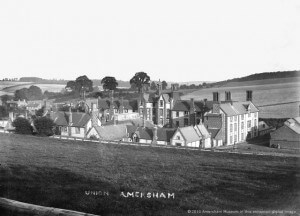

The central flint and brick building designed by George Gilbert Scott was built in 1838 in Tudor style with unknapped (not split to show the dark stone inside) flints and red brick. It was originally the Workhouse for the Amersham Union of Parishes and then became Amersham Hospital. As part of the Hospital Private Finance Initiative, when a new hospital was built recently the old part was converted into private apartments. The building together with the gatehouse and the front boundary wall are all listed grade II. (The photo to the right was taken by George Ward in 1910).

Listen to David Revel talking about the Workhouse – “The Institution”

This article by Dr Michael Brooks was published in the Amersham Society/Amersham Museum newsletter and is reproduced with permission.

Workhouse

Also see Buildings by George Gilbert Scott in the Amersham and Chesham area

Under the terms of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 separate provision for the poor in every parish was abolished. Up to 20 (or occasionally even more) parishes were obliged to join a Union with resources concentrated in the largest or most dominant town in each area. Each union was to be run by a Board of Guardians who would be enabled to raise a poor rate across the union to pay for the scheme. Amersham was chosen as the centre for the local union, to the disgust of Chesham whose population was in fact larger than that of Amersham.

The Amersham Union covered some 111 square miles with a population of just over 18,000 souls. It included the parishes of Amersham, Beaconsfield, Chalfont St Giles, Chalfont St. Peter, Chenies, Chesham Bois, Chesham, Coleshill, Great Missenden, The Lee, Penn and Seer Green. A new Board of Guardians was established and met for the first time on 30th March 1835.

Amersham had had a workhouse or ‘poor house’ from 1617. This had been in four different locations, with overflows in four other houses by the middle of the 18th century. In 1780 the workhouse was at 22-28 Whielden Street at the corner of Whielden Green. In 1783 there were 146 inmates with 24 on outwork relief out of a population of 2,500.

Seven of the other parishes also had workhouses established under the old Elizabethan Poor Laws but by 1835 some were in a wretched condition. In April 1835 the Poor Law Commissioners at Somerset House sent an Inspector to advise on the most suitable building to be developed as the central workhouse for the union. The Inspector reported from the workhouse at Lambeth on 15th April as follows:

Having visited the houses in the Wycombe Union I went to Amersham and waited upon Mr Marshall, the Clerk to the Guardians, and obtained from him the names of the parishes or places included in the Amersham Union and with one or two exceptions the poor are as badly off as in the Wycombe Union, particularly at Penn.

I consider it impossible to describe the misery I saw at Penn and I cannot believe it is known to the neighbourhood that any human beings are in the dreadful state I found them, being almost in a state of desperation – men, women and children occupying and living in the same room and that without flooring, it having been taken away for firing; the only beds I could find were straw, covered over with filthy rags and so infested with vermin that I was obliged to change my clothes as soon as possible. This has also been the case in some parts of the Wycombe Union. It is most disgraceful the poor should be so neglected as it must lead to the very worst of vice.

Amersham House is very clean but it is not calculated to offer advantagesfor good management. Fearing of alterations in conformity with the new laws they keep the contractor as master from week to week. The house is not the property of the parish but rented to T. Drake Esq., at £30 per annum. This amount would keep a workhouse in repair, therefore I don’t consider it advisable to continue the use of it, as other houses in the union, the property of the parish, are better adapted as a workhouse.

The Chesham house is better situated for a workhouse but great alterations would be needed. The present number of inmates is 58.

Chenies. A new house built by the Duke of Bedford – there are 10 children and 1 woman. This little house offers a desirable home for children, having arrangements that would answer well. It sleeps 82 persons and by extending the wings it would offer room for all the pauper children in the union.

Chalfont St Peter. Inmates 21. The house built in 1824 in good repair – but adjoins other-houses…could only sleep 58. Much limited for ground. Badly off for water.

Chalfont St Giles. 31 Inmates managed by a person at a salary of £15 p.a. The house is badly situated and not worth considering~

Penn. 10 inmates. Master out, gone a mile to get 2 pints of beer. This house was built for a workhouse and if no objection to its situation, there can be no objection to its arrangements, for although I’ve before stated the wretchedness to be found at Penn, I beg to call the Board’s attention to the capabilities of the house. The various offices are good but much out of repair, as is the whole building, but strong enough to carry any height that may be wished, and if the wings are carried out a given distance this house would hold all the adult poor of the Union. It is opposite a church, offering an advantage over many houses for spiritual devotion. There are three staircases to this house.

Beaconsfield. Inmates 15. House very much out of repair. In confined situation and of bad construction … not worth considering.

Having surveyed carefully all the houses in the Amersham Union, I am of the opinion that the house at Penn is the most desirable for the adult poor, as I am sure, was a new house to be built, it would not in many respects offer more accommodation or comfort than this, but as I find a deal of feeling amongst the various Guardians to have the house in their respective districts, I respectfully leave which shall be the house with the Board.

The Board of Guardians of the Union duly considered this report and decided that the Penn House (which still exists) would not be suitable. As an interim measure it was decided that all the male paupers should be accommodated in the Amersham Workhouse in Whielden Street, the female paupers to go to the Chesham workhouse and all the children to that at Chenies. This decision was widely resented as married couples and families would be split up. Many of the poor had at that time never moved outside their home parish and it felt as if they are being sent to some foreign country.

The result of the decision was a nasty riot on 23rd May 1835 when ten elderly paupers and a boy were being transferred by cart from the Chesham workhouse to Amersham. An angry mob followed the cart, jeering and throwing stones at Mr. William Lowndes, the luckless official who was responsible for the transfer. As the cart slowed up the hill from Chesham the mob were able to liberate the paupers and they left poor Mr Lowndes in a pool of blood in a ditch near Chesham Common. It was only after a detachment of the then newly-formed Metropolitan Police was summoned from London and had arrested the ring-leaders that the transfer was finally effected some days later.

In view of the increase in the numbers of paupers from the enlarged catchment area, the Board of Guardians found it difficult to supervise the staff in the three separate locations. James McGregor, an ex-Grenadier Guard Sergeant, who had been appointed to supervise the female paupers in the Chesham Workhouse, had to be dismissed on 18th November, 1835, after making one of the inmates pregnant.

The Board therefore decided on 28th February 1837 that a new central workhouse should be built in Amersham. Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake provided 3½ acres of Meeting House Platt in Whielden Street at a cost of £300. Sir George Gilbert Scott designed the building in an ‘Elizabethan’ brick and flint style, the original plans and drawings for which are held in County Records in Aylesbury. Gilbert Scott was a Buckinghamshire man who lived in Latimer as a youth. He worked on many churches and other workhouses in the County. Designed to hold up to 330 inmates it had separate wards for men, women and children, vagrant and tramps’ wards, an infirmary for sick inmates and a luxuriously-furnished board-room.

Work began in 1838 but the original builder, Henry Jacob of Northampton went bankrupt. The work was finally completed by Messrs Page and Stimpson on 28th May 1839. The final cost to build and equip ‘The Union’ came to £7,000. When it opened on 29th September 1839, with Daniel Smith as Master, Whielden Street was re-named Union Street to commemorate the event. Whielden Street and Lane were named after Ralph de Whielden who had acquired land locally after the dissolution of the Monasteries. He at one time owned The Griffin Inn. The street officially resumed its old name after lst April, 1930, when Buckinghamshire County Council took over the workhouse renaming it The Amersham Public Assistance Institution. The 1897 Ordnance Survey map however still called it Whielden Street.

The Board of Guardians controlled the workhouse, meeting every fortnight in the Boardroom which was kept warm in winter by two fires tended by the inmates – in contrast to the cold, miserable spartan conditions in the wards. The Board appointed a Master and Matron who were responsible for day to day running of the establishment under strict rules which now seem very harsh (see the end of this article).

However management must have been very difficult with paupers, some old and sick, imbeciles, children and babies, pregnant women and vagrants all under the same roof. Money was always tight as can be seen from the Account Books preserved in County Archives. Partitions were erected to keep men, women and children separate. (Fuller details of the conditions within The Union may be found in ‘The History of Amersham Hospital’ by Nicholas Salmon, a copy of which is in Amersham Museum.)

The Guardians were responsible for education of the children under their care who were made to attend local schools, where their lives must have been a real misery with incessant teasing because of their origins and their workhouse clothes. Later in the 19th Century schoolteachers were employed to teach in the Union. It should be remembered that at that time children were sent out to work at a very early age and their placement was also a responsibility of the Board.

The provision of outdoor relief had also devolved to the Board of Guardians from the Overseers of the Poor. The Board employed Relieving Officers for this purpose. In 1863 they reported to the Board as follows: “Here is a case of a widow with two children – boys of 11 and 9 years old. The elder in service earns £1 a year, his mother washing and mending for him. The widow and her younger son earn about 2/6d weekly by plaiting straw for the hat trade. The rent of their cottage swallows 1/6d and they receive outdoor relief of 1/- and two loaves of bread. Both boys appear weakly.”

Tramps and vagrants in possession of a pass were entitled to a meal and a night’s lodging in the Tramps’ Ward, but they were expected to do a day’s work before leaving – jobs such as breaking flints for the roads or chopping up railway sleepers for firewood. Women were expected to assist in domestic work and the carrying of fuel and water within the workhouse.

Fit young paupers, especially those with young families, were encouraged to emigrate to Australia. The Amersham Guardians were prepared to find the sum of £10 per head from the Poor Rate. Great Missenden Poor Rate only allowed £8 per head and Chesham a mere £6 per head. The advantage to the Guardians was that these paupers then ceased to be a drain on their funds. Many of the emigrants thrived in Australia. It is interesting to remember that after the end of the 1939-45 War there was a wave of emigration to Australia – an assisted passage costing £10 per head!

The Account Books of the Amersham Workhouse and the Minute Books of the Board of Guardians have survived and give a marvellous, though often chilling, pictureof what life was really like in the workhouse. The Parish Registers of St Mary’s Church, Amersham have also survived and date from 1539 except for those for the years 1542 to 1560. From these and the Account Books of the Overseers of the Poor of Agmondesham (1613-1800) it is possible to determine the names of all the paupers, the work they did, their spartan diet and the cost of their coffins and shrouds.

Fortunately by the end of the 19th Century public opinions began to change. The lot of the ‘deserving poor’ certainly turned for the better. Conditions in the Union became much more tolerable with better diet, greater freedom, nursing services, school for the children, married persons allowed to sleep together, with treats at Christmas and at mid-summer. Beer and tobacco were permitted – a weekly allowance of 1 oz. of tobacco for the old men is recorded in 1892, together with an allowance of tea, milk and sugar for the old women, above the normal ration. The inmates were allowed to go for walks in the town and have visitors freely.

By 1900 the parishes of Ashley Green, Chartridge and Latimer had been added to the other 12 parishes in the Union. Following a significant increase in the numbers of the sick and mentally infirm, a new infirmary was built on the Union site in 1903 to replace the sick ward. The sick poor from the whole area had been admitted there from 1900. There was at that time no hospital service of any sort for the general public. In 1906 another new block was built for accident cases and for contagious diseases, the latter having previously been sent to the Pest House on Gore Hill.

From 1924 the infirmary block became known as St Mary’s Hospital and was increasingly used for the people of Amersham and the surrounding area, though the wealthier members of society still went to High Wycombe, Aylesbury or to the London hospitals.

In 1925 there were 140 inmates in the workhouse, 70 being sick and 50 mentally or physically infirm. Tramps were a great problem as they came in large numbers, as the food was better and the tramps’ wards more comfortable than elsewhere. 10,977 tramps passed through the wards in 1925! The tramps’ wards were not finally to close until 6th June 1939. On 1st April 1930 the administration of the Union Workhouse passed from the Board of Guardians to Buckinghamshire County Council, and the Union was divided into the Amersham Public Assistance Institution and St. Mary’s Hospital.

When war was declared in 1939, parts of the main workhouse and the hospital were commandeered to provide an Emergency Services Hospital for both military and civilians. Prefabricated huts were built on the site by Canadian Forces in 1939/1940. The Local Agricultural Office (important for implementing war-time food production in the area) was also housed in the Union building though callers were forced to wait in the adjoining mortuary. The Public Assistance Institution maintained the nursery and geriatric wards and part of St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington moved in to run the main hospital services, except for an emergency Maternity Hospital which was established in Shardeloes Mansion. In 1945 there were 138 beds in the old Public Assistance Institution and 280 beds in the emergency services hospital huts.

The National Health Service Act of 1946 abolished the old Poor Law system and Amersham General Hospital, which had in effect been established in 1945, was officially acknowledged as such. This was confirmed when the NHS began on 5th July 1948; the hospital was under the control of the Oxford Regional Hospital Board. The Shardeloes Maternity Unit closed on 10th February 1948, by which time 5,200 babies had been born there.

George Gilbert Scott’s workhouse survived for a time as the administration block of Amersham Hospital and it was given Grade 2 listing. This caused problems with later hospital expansion as the block was considered tobe unsuitable and it was decided to sell it off together with other adjoining buildings and land for private development. The old workhouse has been converted to up-market housing and other housing units have been built on the site.

One senior Physician, now living there, has said that his mother had always told him that if he didn’t work harder he would end up in the workhouse and now he has! The sell-off of the land does now seem to have been very short-sighted as there has been major hospital expansion and the shortage of adequate car parking is having a serious impact on the Old Town.

A summary of the Rules for the Amersham Union Workhouse 1838

1. Numbered workhouse uniform to be worn at all times

2. No personal possessions to be allowed.

3. A regular time-table to be strictly adhered to.

4. All meals to be eaten in complete silence.

5. Inmates to be strictly segregated according to sex.

6. Attendance at the Church of England chapel compulsory on Sundays.

7. Rule-breaking to be punished by a cut in rations or a spell in the Refractory Ward.

8. Harsh difficult work to be performed by all fit inmates.

9. No beer or tobacco to be allowed.

10. Sons and daughters wherever possible to be responsible for paying maintenance according to means—the amount to be determined by the Board of Guardians.

Rule 6 caused great resentment as many of the paupers were non-conformists. Rule 9 was relaxed later in the 19th Century. Rule 10 led to many problems with relatives refusing to pay or contesting the amount of the assessment – especially as in the early days of the Union, visiting was not allowed or at least actively discouraged.

A postscript about the Amersham Union in 1835

(report based on the Provincial Medical Association records)

The Poor Law report 1840 has an interesting article about a dispute with local doctors about their charges. When the Amershm Union was formed in 1835, the board of guardians asked local doctors to continue their service, but only offered to pay 2 shillings (10p) for each case of illness and accident, which was rejected as being totally inadequate. The doctors suggested increasing the amounts according to the distance of parishes and the board made a slight increase on their first offer, to 2s.6d. 3s., or 3s.6d. per case, according to the total number attended, but refused any increased rate for distant parishes.

The majority of the surgeons thought it unreasonable but judged it advisable to undertake the contract, but the practitioners in the Chesham district, which contained a population of 6,300, and extended nine miles by seven (consequently involving the longest journeys), declined attending the distant parishes, unless an increased rate per case for so obvious an outlay was agreed.

The board, deaf to arguments, advertised the district, and appointed a youthful candidate from London. Before the formation of the union, the medical salaries amounted to £377 per annum, and the usual extra charges to about £100. At the close of the first year, the total payments to the medical officers were £255, being a reduction of more than £200 per annum. The payments for the distant parishes amounted to less than one-third of the former salaries.

The dissatisfaction of the new medical officer was great, but that of the poor still greater, because did not have the experience to treat their diseases. The guardians then relinquished the payment per case and returned to fixed salaries, but rather than abandon the gentleman whose reply to their advertisement had relieved them from their difficulties, they increased his rate of remuneration for the distant parishes, thus admitting the justice of the principle for which the established practitioners had originally contended.

At the beginning of the second year, the medical officer was taken ill, and consequently unable to attend to his duties. The parish officers were applied to and they requested one of the established practitioners to undertake the care of the sick. This doctor thought it right to obey the call and attended the poor of the district for a week. The board of guardians, in return, refused to pay for his attendance; had the effrontery to suggest that it was usual for practitioners when ill to assist one another gratuitously; and, to crown all, informed their unfortunate medical officer, that if payment were demanded (which they knew it might be legally), they should require him to pay it, as he had undertaken the contract!

Some extracts from the Bucks Herald about the Workhouse

15th July 1848 ‘On Tuesday last, the inmates of this Union held their annual gipsy party, in a meadow belonging to T. T. Drake Esq.. Everything was done to make them comfortable and happy, and if one may judge from their countenances they were indeed so. Old and young joined in the festivities of the day with hearty goodwill.’

26th January 1856 ‘The Workhouse – Two young men, named Edward Penn, aged 22, and Joseph Bedford, aged 18, able-bodied inmates, were committed to the House of Correction, on Friday last, by the Rev J.T. Drake, for a fortnight, for unlawfully wasting and spoiling some of the bread belonging to the establishment. Their conduct while in the lock up was said to be infamous.’

20 January 1877 “DRUNKEN PAUPERS – The master reported that two inmates of the Union had been out and returned drunk. One, a wooden-legged man, had been granted two hours’ leave to get his leg repaired, but stayed away six hours and had returned very drunk and abusive, whilst the other, an old Welsh woman, had some brandy given to her at Amersham and had the greatest difficulty in returning, falling down continually and having to be almost carried into the House… This being the first time the master had reported them, no punishment was inflicted on them, but they were warned that on a repetition of the offence they would be sent before the magistrates.”

13th January 1883 ‘The Discipline of the House – Mr Trebutt, the master, complained of the conduct of some of the female inmates of the House, who were parents of the children there. They had been allowed in the past to visit their children daily, and had been in the habit of taking portions of food to them. This custom had a very baneful influence, and in a great measure checked the discipline of the House, and was altogether most objectionable… It was at once resolved that the parents should be allowed to visit their children once a week only.’

Click for more information about the Amersham Workhouse or to see a list of the workhouse inhabitants in 1881.