This page was written by John Clutterbuck with help from Julia Wise, Historic Environment Records Officer, Buckingham County Council and Edward Copisarow, of Shardeloes. Extensive reference has been made to A History of Amersham by Julian Hunt and to the Victoria History of the Counties of England (VHCE)

Shardeloes before the arrival of the Drake Family in the Seventeenth Century

The Misbourne Valley has yielded evidence of occupation during thousands of years. Finds have included flints from various periods of the Stone Age. In the 1980s, there were Iron Age and Roman finds from the construction of the Amersham by-pass and from an archaeological excavation at Mantles Green. Field walking has also yielded Roman coins, bricks and tiles, pottery, bronze bowls and ornaments.

In a letter dated 30 September 1753, J Collins wrote to the Rev Dr Stukely, Queen Square, London: “A great number of that emperor’s [Carausius] coins was found near that place [Amersham] about 2 years ago, as Mr Drake was making a large sheet of water which covers 40 acres, but most of ‘em are in the hands of the lord of the manor. The workmen, as they were digging, laid open a curious burial field, in the form of a minced pye, built with flints, several bodys found therein, some with ear-rings, all dropt to dust soon after they were exposed to the air. Near to that place I discovered a Roman pavement, & took up several bricks, about an inch square out of the margin of the pavement, of divers colours. Mr Drake has been acquainted with it, & said he durst not open it till a proper opportunity, for fear the workmen’s shovels damage it, & nothing has been done since.”

The work described by Mr Collins was part of mid eighteenth century activity surrounding the construction of the present Shardeloes House and the renovation of the Shardeloes estate, including the lake. (Carausius was a rebel, a self-styled emperor of Britain and Gaul. During his short reign at the end of the third century, he issued coins of unusual purity.)

The Mantles Green site seems to have been an outbuilding, with facilities for iron making. It would be expected to have been complementary to a larger villa nearby. The presence of the latter would have been implied by Mr Collins’ reference to a tiled “pavement of divers colours”, i.e. a mosaic floor. The main villa has never been found. During a period of drought in 1992, P Struth, an Oxford student, conducted field walking of the dried up Shardeloes lake-bed but found no pottery, bricks or tiles that might be associated with a villa. It is perhaps unsurprising that no trace of Roman material was found on the lake bed in the 1990s. The lake had been drained in WWll, the parkland ploughed up, and silt from the lake had been spread over surrounding land.

Julian Hunt states in A History of Amersham that, by the time of the Domesday Book (1086), Geoffery de Mandeville had become the predominant land holder in Amersham. There is nothing in the Domesday Book which can be unequivocally related to Shardeloes, but Hunt suggests that Castrupps Close, mentioned in a seventeenth century lease, might have been the hitherto unidentified land and mill at Cattesropp, and that the mill pond at Cattesropp might have eventually have formed part of the ornamental lake at Shardeloes.

Whether or not the property at Castrupps/Cattesropp contained one of the three Amersham water corn mills mentioned in the Domesday book to have been eventually incorporated into an ornamental lake at Shardeloes, the first mention of the name Shardeloes (in this context) occurred in 1308, when part of the Amersham estate owned by Lawrence de Broc was granted to Adam de Shardeloes. The Victoria History of the Counties of England states that it was from Adam de Shardeloes that the estate “took its distinctive name of Shardeloes Manor”. The land reverted to the de Broc family, who transferred it to Simon de Brereford.

De Brereford was on the wrong side of a dynastic struggle between a young Edward lll on the one side, and his mother Queen Isabella and her consort Roger Mortimer on the other. Edward lll prevailed. Mortimer was executed and his ally Simon de Brereford forfeited Shardeloes to the king. A lease was granted in favour of William Latimer in 1331, and John Latimer received a further grant in 1334.

By the early fifteenth century, Shardeloes was in the possession of Henry Brudenell, and remained with the Brudenell family until the mid fifteenth century, when it passed through the marriage of Elizabeth Brudenell to Thomas Cheyne. Shardeloes was alienated from the Cheyne family to Henry Fleetwood in 1590, who in turn alienated it to William Tothill in 1595. Julian Hunt states “William Tothill added to his Buckinghamshire estate in 1595 by buying two small properties, adjoining Wycombe Heath, called Woodrow and Shardeloes. These estates had substantial houses on the hillside above Amersham, both of which could be let to wealthy tenants, but the real value was the unstinting grazing on Wycombe Heath … on the south-west boundary of Amersham … and the potential for enclosing more land from the common.”

The early Drake Family – 17th century to late 18th century

From the early seventeenth to the mid twentieth century, Amersham was dominated by the Drake family of Shardeloes. In his introductory note on the Drakes, Julian Hunt states that they “increased their family fortune by securing valuable sinecures and marrying wealthy heiresses”.

The Drakes came from Ashe in Devon, via Esher in Surrey, and some have wrongly claimed that they were related to Sir Francis Drake. Julian Hunt states in A History of Amersham, “the most creative genealogists have been unable to establish a direct connection with the Elizabethan mariner.” Much of what follows on the Drake family is based on Julian Hunt’s book.

The Drake family inherited the manor of Shardeloes from the Tothill family through the marriage of Joan Tothill, co-heir of William Tothill, to Francis Drake of Esher. Julian Hunt states that “Frances Drake was a godson of his more famous namesake”. The first Drake to live at Shardeloes was William, later Sir William (Bt.), who inherited Shardeloes as the grandson of William Tothill. This particular William Drake (1606-69) purchased the Borough of Amersham from the Earl of Bedford in 1637, and built the alms houses in Amersham High Street in 1657. Confusingly, a number of other prominent Drakes were also called William.

William Drake was a Royalist, playing no active part in the civil war. Nevertheless, in 1645 Parliamentary forces attacked Shardeloes, burnt barns, stables and outbuildings, and caused some damage to the house. William Drake subsequently spent some time out of country, returning after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The VHCE states that a chapel was attached to Shardeloes “as being remote from the village church”. In 1668, a fellow of St John’s Oxford was appointed curate.

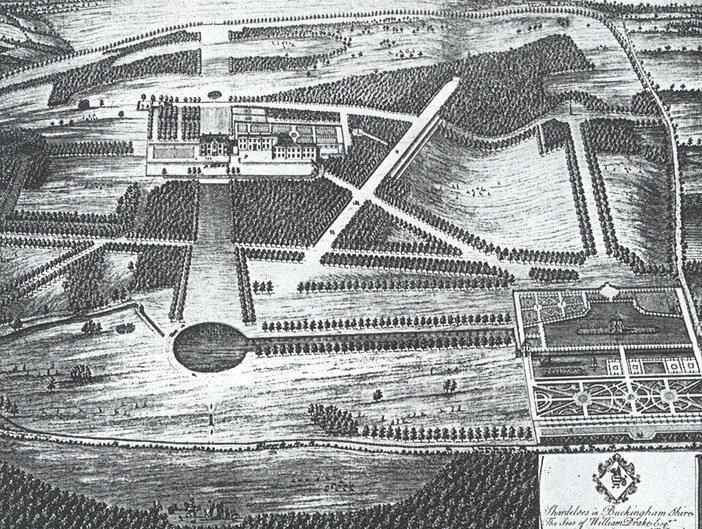

When Sir William Drake died in 1669, his nephew, also William Drake (Kt.) (1651-90), inherited the estate. He married an heiress, and was responsible for the building of the Market Hall in 1682. Montague Garrard Drake (1692-1728) did his duty by marrying an heiress, but had a lavish lifestyle. He started the process of renovating Shardeloes by building a range of offices and stables, to the west of the main building, and had the road to Aylesbury moved to the north of the lake. He died of gout in Bath aged 36, leaving loans and mortgages for his successors to pay off.

Montague Garrard Drake was succeeded in 1728 by his young son, William Drake (1723-96). Julian Hunt states that “William Drake was returned as MP for Amersham in 1746. He held the seat until his death in 1796, but there is no record of his ever having made a speech in the House of Commons.” His eldest son, William Drake (1747-95), sat in Parliament from 1768 until his death and spoke frequently, “generally advocating caution in public expenditure.” …. William Drake the younger married two heiresses. … The Gentleman’s Magazine reported that “He has left an immense property partly acquired by marriage, and partly by some collateral branches. Had he lived to inherit that of his father, he would have been one of the richest men in the country.”

Construction of the present house under William Drake

This section on the construction of the present Shardeloes House and the renovation of the grounds of the estate is based on a presentation in the Amersham Museum by Edward Copisarow of Shardeloes House, and on further research by him.

This section on the construction of the present Shardeloes House and the renovation of the grounds of the estate is based on a presentation in the Amersham Museum by Edward Copisarow of Shardeloes House, and on further research by him.

Most of the work to rebuild Shardeloes took place under William Drake (1723-96), who went on the Grand Tour from 1742-46. In 1747, he married Elizabeth Raworth, an heiress. The injection of funds enabled William Drake to rebuild Shardeloes between 1758 and 1766 at a cost of £19,000.

Stiff Leadbetter of Eton was initially appointed to rebuild Shardeloes House. He was associated with some 20 country houses, including what is now the administration block of Bath University, Nuneham Courtney and Langley Park.

A young Robert Adam provided designs for the interior including chimney pieces, woodwork and plasterwork at Shardeloes. When Leadbetter died in 1766, Adam persuaded William Drake to remodel the exterior. Robert Adam designed a large portico on the north side, as part of the first country house commission on which he was engaged to work both inside and out. Adam provided designs for the portico, the north east and south east elevations of the house and the present outbuildings.

By 1775, William Drake had found the climate at Shardeloes injurious to his health and had moved to live in Twickenham, handing Shardeloes over to his son (also William, who predeceased him in 1795). William Drake the elder died in 1796, leaving his estate to his second son Thomas Drake Tyrwhitt-Drake, who in 1775 employed James Wyatt, another giant of the neo-classical age, to help him squeeze more books into the library. There are records of Samuel and Lewis Wyatt working at Shardeloes until after 1800.

John Linnell was a top London furniture maker of the latter part of the eighteenth century. He frequently worked alongside Robert Adam. Linnell took on the job of fitting out Shardeloes, partly executing designs by Adam, mostly making furniture to his own designs. He also supplied upholstery, curtains and carpets. Linnell supplied a set of faux bamboo chairs 10 in 1767, perhaps for the large parlour. Eight burnished gold elbow chairs and two sofas to match were supplied for the drawing room and remained at the house until 1947, when they were sold and subsequently presented to Princess Elizabeth as a wedding present in her new home at Clarence House.

The landscaping of the grounds of the Shardeloes estate in the seventeenth century was principally attributable to three men. The first was Charles Bridgeman, who laid out Hyde Park and who probably advised William Drake’s father on moving the Aylesbury road to the far side of the Misbourne. The second, Nathaniel Richmond, had been a foreman of Capability Brown. Richmond may have been responsible for the design of the enlarged the lake. He was responsible for the pleasure ground immediately surrounding the House and is often cited as the inspiration behind Humphrey Repton. Finally, Humphrey Repton himself. Repton surveyed the estate in 1792 and 1793. The Museum has a copy of the Red Book which was presented to William Drake junior in 1794 by Repton. His designs were only for the north park, and perhaps due to the death of William Drake junior in 1795, little if any of his design was executed.

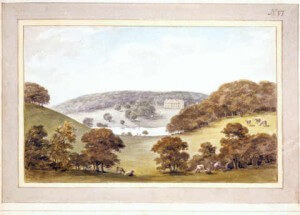

In 1753, J Collins was writing about work being under way to enlarge the lake to 40 acres. Prior to that, and before the present Shardeloes was built, the lake comprised a straight canal and a circular feature, as shown in a 1729 picture by Badesdale and Rocque. A 1762 picture by James Rocque, based on a survey of 1762, shows a much larger lake, consistent with the report from J Collins. There was a downpour in the winter of 1774 which fell on frozen ground, leading to flooding in Amersham. The surface area of the lake may subsequently have been reduced. The profile of the lake shown in the first draft Ordnance Survey, dated around 1790, appears smaller than in the James Rocque outline. The modern lake may be similar in extent to that in the mid-eighteenth century lake.

The Tyrwhitt-Drakes – late eighteenth century to 1939

When William Drake the elder died in 1796, he was succeeded by Thomas Drake Tyrwhitt-Drake (1749-1810), who inherited Tyrwhitt property in Lincolnshire and elsewhere when the male line in that family died out. To acknowledge the inheritance, he incorporated the name Tyrwhitt within his own. Thomas Drake Tyrwhitt-Drake and his brother John Drake married two sisters who were co-heirs of the Rev. William Wickham of Garsington in Oxfordshire.

The family fortunes changed in the early nineteenth century when the Drakes encountered fox hunting, described by Julian Hunt as “a costly pastime which diverted the Drakes from the care of their estates, and which led to their being attracted to women who were good riders rather than wealthy heiresses.” The downturn in Drake family fortunes may also have been influenced by the agricultural depression and the low value of land after the Napoleonic Wars.

Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake (1783-1852) inherited the Shardeloes estate from his father in 1810. He extended Shardeloes Park by incorporating Wycombe Heath land allocated to him under an Enclosure Act. He also received land from the enclosure of Amersham Common. According to Julian Hunt, he was the first of his family to be obsessed with fox hunting, a pastime which was followed at Shardeloes by most succeeding Tyrwhitt-Drakes.

Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake was said to have stopped George Stephenson and Son from building the London to Birmingham Railway along the Misbourne valley in the 1830s due to concern over the view from Shardeloes. He may also have had qualms over the railway’s possible effect on fox hunting.

Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake was MP for Amersham from 1805 until the Reform Act of 1832, but rarely attended Parliament. Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake was succeeded by his son and namesake, Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake (1818-88), in 1852. The latter sold land in Amersham Common to the Metropolitan Railway Company, a prelude to the building of the line from Marylebone to Aylesbury. The station at Amersham was opened in 1892. The line to Aylesbury from Amersham is mostly hidden from Shardeloes House in a cutting on the north side of the Misbourne Valley. Although the Drake family intended to develop land near the railway station in the early 20th century, there was little development before World War l.

In the late 19th century, a racecourse was established on the east side of Shardeloes Park. Races were held on Easter Mondays, but not run on Jockey Club rules. The event ceased when a jockey was killed in a fall. Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake was succeeded by Thomas William Tyrwhitt-Drake (1849-1900), William Wykeham Tyrwhitt-Drake (1850-1919) and Edward Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake (1887-1933). In 1928, the Griffin, Crown and Swann Inns, and many Drake properties in Amersham High Street were sold. Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake (1893-1956), who inherited in 1933, was the last of the Drake family to live at Shardeloes. Thomas Tyrwhitt-Drake moved to Little Shardeloes in Amersham High Street where he died in 1956.

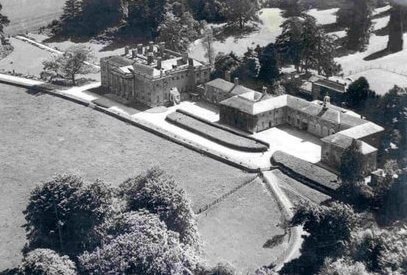

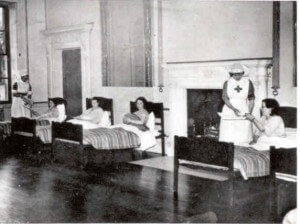

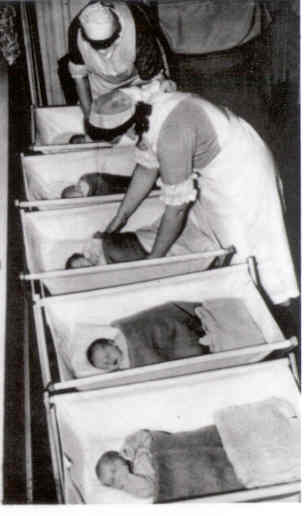

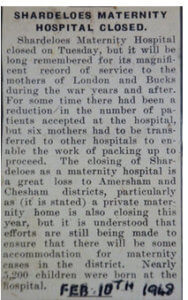

In 1939, Shardeloes became a maternity home for expectant mothers from London. About 5,000 children were born there during WWll, including Sir Tim Rice, lyricist and author. There is a separate page telling the stories of some of the babies in their own words.

Shardeloes since World War 2

Shardeloes continued to be used for a while as maternity home after the War, but was later empty and was threatened with demolition. In the 1950s, an average of one stately home was being demolished each week and Shardeloes was earmarked for demolition in 1957. Developers had planned to re-use the bricks to build many new homes on the site. The newly formed Amersham Society campaigned to save the house, and succeeded in having it Grade I listed. By 1961 it and the nearby outbuildings had been converted into apartments.

Shardeloes continued to be used for a while as maternity home after the War, but was later empty and was threatened with demolition. In the 1950s, an average of one stately home was being demolished each week and Shardeloes was earmarked for demolition in 1957. Developers had planned to re-use the bricks to build many new homes on the site. The newly formed Amersham Society campaigned to save the house, and succeeded in having it Grade I listed. By 1961 it and the nearby outbuildings had been converted into apartments.

See also an article about the Drake family. An account by someone who know the house when the Tyrwhitt-Drake family lived there can be seen here. Read also about the Shardeloes ghost.

Click on any of the photographs below to enlarge it and to see the description. Then click on forward or back arrows at the foot of each photograph. To close the pictures, just click on one.