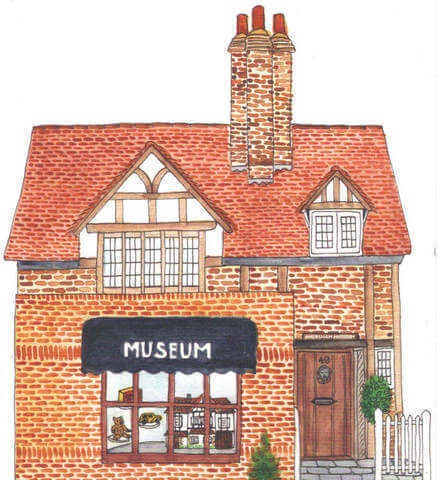

The Museum building is part of a late 15th century hall-house, probably built for a merchant around 1480. Much of the original timber structure of the roof above the central hall, the carved arch-braced truss, and part of the solar wing can still be seen. The upper half of the original hall window also remains at the rear of the house. A detailed cut-away model on display shows the likely structure of the house in about 1500.

The Museum building is part of a late 15th century hall-house, probably built for a merchant around 1480. Much of the original timber structure of the roof above the central hall, the carved arch-braced truss, and part of the solar wing can still be seen. The upper half of the original hall window also remains at the rear of the house. A detailed cut-away model on display shows the likely structure of the house in about 1500.

Archaeological investigation of the floor of the hall revealed a central hearth. This would have been used to heat the house before the chimney stack and fireplaces were added in about 1580. The construction of the hearth and surrounding tiles can be viewed through a glass panel in the floor of the museum. There are some interesting “witch marks” carved in the roof timbers. (See the explanation at the foot of this page.)

When the chimney was built in about 1580, a first floor room with a fireplace was created within the hall and following this a gable window was added to this room. Later alterations to the house included brick infill between the structural timbers, remodelling the ground floor fireplace, the addition of a staircase and doorways cut through the structure to connect the first floor rooms.

The hall-house was sub-divided between members of the Hunt family, who were Maltsters in the early 17th century. By 1851 the tenant was Henry Toovey, a furniture broker, and The Times in 1928 reported that Herbert Frederick Toovey, a 30 year old antiques dealer, while cleaning a piece of mahogany ran a splinter into his finger and died of tetanus. The house remained in the Toovey family until the death of Ronald Frank Toovey, who had built an antiques shop at the front. (He died in 1980 without leaving a will and his estate was eventually split between 30 heirs, most of whom were found via an heir hunter, Mr Birchwood.)

The hall-house was sub-divided between members of the Hunt family, who were Maltsters in the early 17th century. By 1851 the tenant was Henry Toovey, a furniture broker, and The Times in 1928 reported that Herbert Frederick Toovey, a 30 year old antiques dealer, while cleaning a piece of mahogany ran a splinter into his finger and died of tetanus. The house remained in the Toovey family until the death of Ronald Frank Toovey, who had built an antiques shop at the front. (He died in 1980 without leaving a will and his estate was eventually split between 30 heirs, most of whom were found via an heir hunter, Mr Birchwood.)  It was then bought in a dilapidated condition for £64,000 to create the Museum. The original house is currently divided between the museum and the adjacent property, although part of the solar wing was demolished in the 19th century.

It was then bought in a dilapidated condition for £64,000 to create the Museum. The original house is currently divided between the museum and the adjacent property, although part of the solar wing was demolished in the 19th century.

Click for a short video about the Museum as seen through the eyes of some visitors. See also some of the plants in the herb garden.

The privy

The privy at the bottom of the garden has been restored. When No. 49 became the home of Amersham Museum, the brick and tiled privy at the end of the garden was in a very poor state. The seat was worm-ridden and the rest of the space was dirty and full of rubbish. The privy was cleared out and the rotten wood was burned and for the next few years it was used as a garden shed, as was its semi-detached neighbour at the end of the garden of No.51. When it was discussed by the Museum team it was generally assumed to be a two holer with the second hole, smaller and lower, presumably for a child. Privies with more than one hole were not uncommon. Six-holers are known and the Roman legions on Hadrian’s Wall had multiple seated facilities.

After many years of neglect a privy resuscitation plan was devised. The building was cleared and it was established that it must have been a single hole provision – there was not enough room for anyone else. Another idea was also corrected. It had been assumed that the privy emptied into the River Misbourne which flows immediately behind the back wall but this wall shows no sign of any vent. There is no irregularity in the brick work and, as most Amersham people know, the river is not reliable. Sometimes the bed is dry for months at a time so it would be useless as a disposal system. Walking along the river behind the High Street houses, many have bridges and the remains of similar privies. There must have been a system of “Night soil men” who crossed the river and emptied the buckets under each hole at regular intervals. This manure, mixed with wood ash by the householders, was passed onto farmers and large scale gardeners as fertiliser, a system still used in rural parts of Asia. Some house-holders would have composted the waste for use in their own gardens.

Once the privy building was clear and an old photo was found (see Buckinghamshire Privies by M Andrew, 1998) reconstruction was started in the winter 2009-2010. Suitable old timber planks and red floor tiles were found in a reclamation centre near Stokenchurch. A skilled carpenter and his mate rebuilt the seating and a bucket was installed plus another bucket with ash and a shovel for covering the waste. An old style rag rug, based on a genuine potato sack, was pegged and placed on the floor. And on a nail in the wall a torn up copy of a pre-war Daily Telegraph was hung on a piece of string. Across the doorway an information board provides a brief history of privies and a huge selection of euphemisms for what we call the privy – some are rude, some scatological and some distinctly political. And for the formal opening the well known historian, Lady Lucinda Lambton cut the ribbon to reveal the new and varnished seat, the rug, the scouring powder and scrubbing brush and essential fly paper hanging from the roof.

Witch Marks

You might miss these unusual marks on your first visit to Amersham Museum. They are carved on to the upper parts of the timber frame of the fifteenth century hall house. The marks are situated directly above the central hearth. They are known as witch marks or apotropaeic marks and were designed to prevent evil from entering the house through the smoke hole.

You might miss these unusual marks on your first visit to Amersham Museum. They are carved on to the upper parts of the timber frame of the fifteenth century hall house. The marks are situated directly above the central hearth. They are known as witch marks or apotropaeic marks and were designed to prevent evil from entering the house through the smoke hole.

Witch marks are often made in the form of letters M, V or W, thought to refer to the Virgin Mary. Sometimes they are circular with petal shapes.

Witch marks are often made in the form of letters M, V or W, thought to refer to the Virgin Mary. Sometimes they are circular with petal shapes.

Click on any of the photographs below to enlarge it and to see the description. Then click on forward or back arrows at the foot of each photograph. To close the pictures, just click on one.