The hidden community in the Maltings

updated by Alison Bailey April 2021

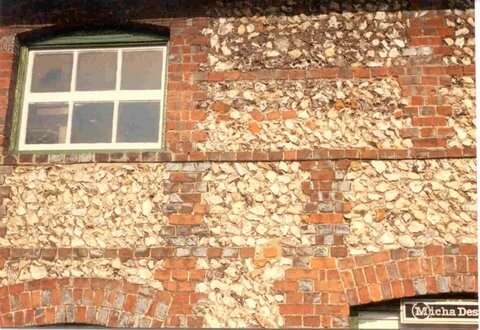

There is a great deal of speculation as to what the future holds for the Grade II listed maltings in Old Amersham as this historic site is currently on the market. Bordered on 2 sides by Barn Meadow, the buildings are clearly recognisable as they still retain characteristic malting features such as the distinctive kiln hoods and long elevations with regularly spaced windows. Few external alterations have been made since the closure of the Weller Brewery in 1929 which adds to the site’s significance, particularly as Historic England believe that only 10 to 15% of identifiable maltings survive.

A sympathetic development would enable these maltings to be better appreciated within the town, but it is vital that any conversion retains the identifying features so that there is more than just a name to indicate the building’s former use.

Maltings Yard

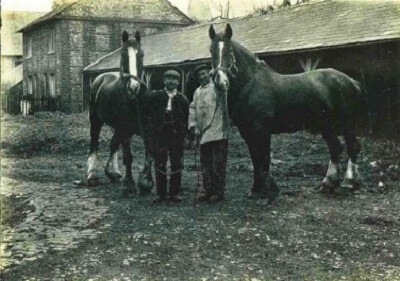

It is not widely known that the Maltings also provided homes for many generations of Amersham families. When the brewery was sold to Benskins, drayman William Hance had been living there for over 20 years, the Bryants and the Greens for over 30 years, and night watchman George North and his wife Sarah (née Green) for 14 years. Before that many other families lived on the site. There were cottages for the maltsters who needed to be close to their kilns and for the draymen who stabled their enormous dray horses in the complex.

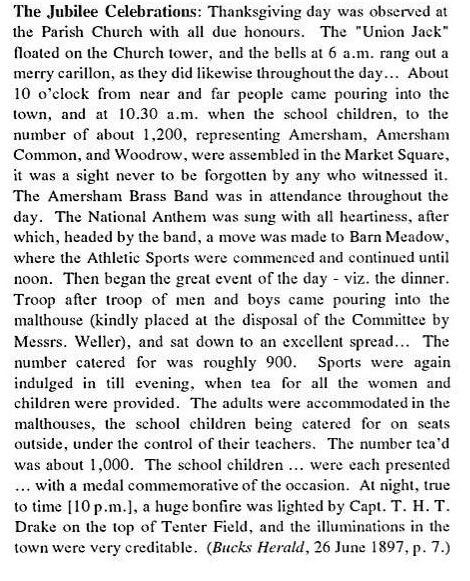

Ann Gomm lived there for nearly 70 years when her husband, Ephraim and her son and grandson, both called Fred, worked for the brewery. After Ephraim’s death she lived in one of the widows’ cottages for another 30 years working as a seamstress. The site was also used for community events. Each year the Sprat Supper was hosted by Wellers when all the townsfolk were invited into the Maltings to eat fish fried on the steel malt shovels.

A Major Investment

Malt is a prime ingredient in the brewing process. It is artificially germinated grain, usually barley, with germination arrested at the critical point by kilning and has been produced in Amersham for 100s of years. There was an early maltings in the market square, now shops, with a kiln at the back. Town Mill was also used until the Weller brothers, John and William, decided to invest in larger-scale floor maltings.

Listen to Jean Archer talking in 1991 about The Maltings

In 1829, they built the new complex on Barn Meadow, possibly on the site of an earlier malthouse, to a specific design for the purpose of making malt. The structures on top of the building were the ventilators for the kilns. They built one-roomed cottages for the widows of the Wellers’ staff, just on the left inside the first entrance to the Maltings. The Wellers gave an annual Sprat Supper inviting all the townspeople to the Maltings where they fried sprats on shining steel malt shovels.

In 1837 The Times reported a major fire: “The malthouse was completely gutted. In its storerooms were about 1,500 quarters of malt, a very great proportion of which has been rendered useless. The premises and stock were insured at £1,500 and the loss to Messrs Weller, by close calculation, will amount to at least £5,000.”

Barn Meadow

Listen to Reg Mason talking about the lake in Pondwicks in 1909

The location next to the river was vital, first to drive the water wheel to power the machinery used to clean the harvested grain, and then to steep the barley. Steeping required vast quantities of water to start the germination process so the river water would have been diverted into the steeping tanks when this was needed and then out into the river again. The maltsters wore wooden clogs to keep their feet out of the water which was always sloshing around the site!

After resting (couching) the barley, it was spread on the growing floor to a depth of 4 to 8 inches. The largest building in the complex contained the main growing floor and shows the scale of the operation. The regularly spaced windows along the long elevation would have had wooden louvres to ventilate the growing floor and maintain an even temperature. The maltsters had to regularly turn the growing barley with a broad shovel to ensure it didn’t mat and to reduce heat build-up. This was hard physical work. Once sprouting the barley, known as green malt, was heated in the kiln for many hours, even days, to halt germination. In the 19th century, kilning was skilled work as this gave the beer its unique colour and flavour. Wellers were rightly proud of their malting process and advertised their beer as “clear to the last drop”.

A community within a community

The kiln fire was central to the life of the community. The many children (the Gomm family had 7!) would gather round to listen to the maltster’s stories or join in a singalong with the draymen, known for their comradeship and cheerful manners. Fred Gomm was a popular singer and always ready to perform for a crowd. 15 draymen were employed at the height of the brewery’s success and some of the horses and drays were housed within the Maltings. The cobblestone stable yards still survive today. No stable hands were employed, so each drayman had at least 2 horses to feed and groom daily which meant that a cottage on site would have been highly desirable.

After the brewery

In 1930 Benskins auctioned the buildings. James Long, a boot manufacturer and property speculator who lived at Top O’ Th’ Hill (now Our Lady’s School) in Chesham Bois bought the Church Street premises and the Maltings with the idea of creating a glamorous country club and leisure centre. William Matthews, a successful builder from Chesham Bois invested in the club. An indoor swimming pool was built, and planning permission for badminton courts applied for. The storey above the growing floor was removed and a viewing gallery created above an enormous maple dancefloor, but the project was never completed. Matthews died tragically on the railway in 1934 and Long decided to concentrate on converting the brewery buildings which did indeed become badminton courts and then a hotel.

It was then bought by Mr McLatchie for fabric printing business, Amersham Prints. They converted the dancehall into a textile factory. In the war it was used for making nearly 7,000 convoy or kite balloons, similar to barrage balloons but smaller, as well as fins for larger barrage balloons, inflatable dinghies for aircraft and lifebelts.

Listen to two women who worked in The Maltings during World War II

Violet Winsor R1_0020

Daisy Caton R1_0019

More recently the complex was rented out as offices, light industrial units, and a gallery. Nevertheless, I imagine that any future development will at least be partly residential. I hope that children will again play in Maltings Yard, and that they will be told stories of the Weller draymen in their red tasselled hats, and will be able to imagine the sounds of the maltsters’ clogs and the dray horses’ hooves, ringing on the old cobblestones.