(including Hodgemoor, Piper’s Wood and the other temporary housing camps)

By Alison Bailey, Elizabeth Barry and David James.

During WWII a number of army camps were established in the woods around Amersham as temporary barracks for troops in training or in transit. According to Bill Wright (listen to his memories here) the town was “alive with army”. Nicolas Salmon and Clive Birch’s ‘Yesterday’s Town: Amersham’ states “Northamptonshire Territorials camped locally and in July 1940, soldiers of the 51st Highland Division, the Gloucesters, the Middlesex Regiment and the Oxon and Bucks Light Infantry were housed in temporary camps built in Rectory and Pipers Woods. The US forces took over Piper’s Wood, which ultimately served as a reception centre for returning PoWs”. There was also a combined services camp based up in the woods behind Latimer House and camps in Chalfont St Giles (Vache Camp), Little Chalfont and Penn Street.

After the war these army camps often became temporary housing camps. The Hodgemoor camp, just off the A355 Amersham to Beaconsfield road became a reception and billeting camp for Polish soldiers and their families. After spending the War in refugee camps in English colonies in India and Africa many Polish soldiers’ wives and children were reunited with their husbands and fathers after sailing to England on the Carnarvon Castle in 1948. Zosia Biegus has collected their stories in her book Polish Resettlement Camps in England and Wales 1946 and 1969 and her website. Hodgemoor provided a safe home to over 150 Polish families after the war in temporary buildings, barracks and Nissen huts. The Polish servicemen were mainly from the Third Carpathian Division in Italy.

Conditions in the camp were basic but it was a proper community, a Polish village with a Church, with its own priest, Father Josef Madeja, an infant school with Blanca Potocka as the teacher, a post office, a shop and an entertainment hall. This hall was used for dances, plays, meetings, National Day Celebrations, weddings and parties. There was a thriving community of Brownies, Guides and Scouts in the camp, a football team and children were taught Polish customs and dances.

According to Zosia there was “a lot of resentment of the Poles at the time even though the Polish Army was the third largest armed force fighting in the West under British command and had been Britain’s only ally from the first to the last day of the war. The Poles were unable to return to their country because their homes had been annexed by Russia under the political settlement at the end of the war. The Poles lost more than their homes, they lost their country!” The camp was eventually demolished in 1962, and apart from a commemorative plaque in Hodgemoor Woods, and the Polish Club in Raans Road there is little to remind us of this extraordinary period of local history.

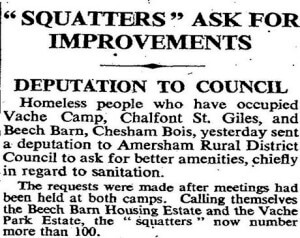

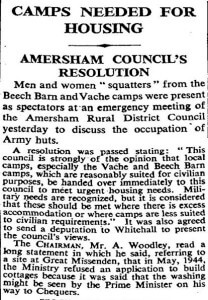

Other camps in the area were soon taken over by ‘squatters’. After the war there was a real housing shortage with many displaced families desperately seeking somewhere to live. The population in the Amersham area had increased dramatically during the war with an influx of refugees, evacuees and families made homeless by German bombers. During the war many were able to stay with relatives or had been billeted in the area often in very overcrowded conditions. However afterwards, families were desperate to find a home of their own.

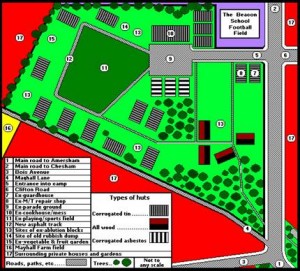

Beech Barn Camp was the name of the army camp situated on the main Amersham to Chesham road just past Bois Avenue. There was a top camp (nearest to Amersham where the Leys is today) with at least 25 huts, then a school playing field and the Beacon Boys School and then the bottom camp with about 7 huts.

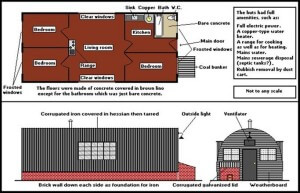

There were corrugated tin Nissen huts, some corrugated asbestos Nissen-type huts, and a few wooden huts in one corner of the top camp. Most of the huts only had a concrete floor with a pot-bellied stove in the middle. There were ablution blocks, water towers, a parade ground, a cookhouse, an officer’s mess and even a dance hall (now the Beacon School dining room). The main Amersham to Chesham road bordered the front of the camp, the playing field and school grounds bordered the right hand side, the backs of gardens in Oakway Road bordered the far side, and Mayhall Lane bordered the left hand side coming back to the road. There was a fence or hedge all around the camp except on the Mayhall Lane side.

Elizabeth Barry, who lived in Beech Barn camp and now lives in Australia, explains in her memoirs how she came to live in the camp: “One day while on a visit to a friend, the conversation came up about ‘Squatters’. We had three local army camps and it was rumoured people in the town were taking over any army huts that were vacant and squatting in them. As my friend and I got further into the conversation, ideas were forming in my mind. What one could do, so could another.

Accommodation was very hard to get just after WW2, much worse if one was alone with children. There were very few people in the position to help and so many in the same ‘homeless’ situation. My friend agreed to ask her husband if he could find out any further news of the ‘squatters’ story, seeing he worked in the Town Centre. She promised to let me know next morning. True to her words, she was over first thing, and told me one of her husband’s workmates had moved his family into a vacant hut in the camp called ‘Beech Barn’. As there were already six families living in the camp, they formed a four-member committee.

My friend advised me to get up to the camp as soon as I could. The word was getting around fast, and others would be following in that direction. Beech Barn and Pipers Wood camps were occupied by repatriated Polish soldiers and other personnel. There were thousands of homeless people in our own country that were still living rough, in air raid shelters, underground stations, even in the ruins of their bombed out houses. Many with just the clothes they stood up in, roaming the street during the day, wondering what tomorrow would bring, with no job, food, or a place to put their heads down, a place to call ‘Home’ It was only natural that we were resentful and disapproved of the occupancy of these camps, it had nothing to do with the Polish people personally.

I took my friend’s advice, although it was a couple of miles up the road, I was soon on my way with the children in the pram. The nearer I approached the camp the more my heart leapt with anticipation. After chatting with one of the committee members, I was told I would have to go on the waiting list. If there was even a slim chance of getting a place of my own, I was willing to wait as long as it took. In the morning my friend rushed over shouting “quick get your things together, there’s a place for you at Beech Barn camp”. Evidently her husband had mentioned to his friend about me as soon as he got to work, and seeing I had two children they would find space for me somewhere. I could hardly believe my good fortune.

I only had the children’s cots, an army canvas’ fold-up’ single bed, and an old chest of drawers, which had been given to me by my friend that morning. I also collected a couple of orange boxes from the general store round the corner. With the children in the pram, surrounded by the last of our belongings, I set forth into another chapter of our lives.

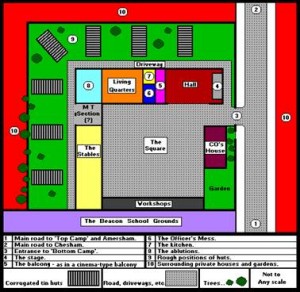

When I arrived at the camp I was met by Margaret Hartley, a member of the Committee, who was to show us where to go. The estate was divided into two camps. ‘Top camp’ and ‘Bottom camp’. We were assigned to the latter. On the way Margaret explained there were no huts available but ‘to get one’s foot in the door’ as the saying goes, we were given the dance hall. I had imagined a moderate social room, so I was not prepared for the spacious dwelling we would be occupying.

For a fraction of a second my thought flashed forward–What ever will I do with all the space? How will I keep my children warm during the cold winter nights? But I would cross that bridge when I got to it, and would solve the problem as I always did, one way or another. My attitude of ‘positive thinking’ generally paid off. As we entered the hall, we were faced with a large stage away at the far end of the hall, to the left was a large recess with seats either side, and between the seats stood a open fireplace with a log fire blazing merrily away, as if bidding us welcome. This was to become the focus point of the living area. The children loved to sit on the seats and listen to stories and would generally fall asleep with the warmth of the fire. The stage became the children’s bedroom, and when I think back now, I have a giggle to myself with the vision of two cots standing in the vast space, as if waiting for the actors to come on stage. In the middle of the hall stood a lonely canvas bed with the chest of drawers beside it. The orange boxes became our food cupboard. The hall became ——-OUR OWN DOMAIN AT LAST!

Later that day we were given the royal welcome by some of the other squatters, who brought a pot of tea, sandwiches and cakes, even bowls of hot soup, which we were very grateful for. This became the regular habit to other families that joined us later. Within a few days I had adjusted to the communal toilets and washing facilities. It was as if we had always been there. The other women were very friendly and soon, a chair, the odd blanket, and other small gifts appeared on the doorstep, which was very much appreciated. The hall being so spacious soon became the children’s playground on rainy days. It seemed every child on the block loved to come to ‘our house’ to play.

I was really blessed with the wide open fire-place during the following winter, although I had to go into the woods daily to find wood, it was well worth venturing out into the cold wind, rain or snow, as I watched my children play happily on two old sacks, that acted as ‘hearth rugs’ in the evenings. Most of us residents paid 12 shillings weekly to the committee, which was deposited into a savings account, with our details for future reference and hopes of the council eventually taking over the estate.”

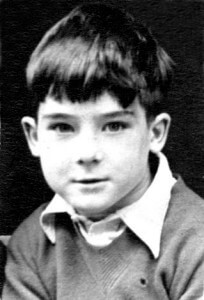

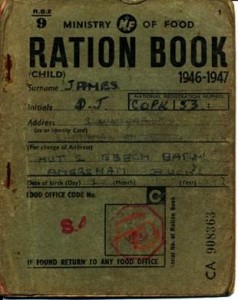

David James, Elizabeth’s son who now also lives in Australia has written in great depth about living with his mom and little sister in the Beech Barn camp on his website and describes those first weeks in the dance hall:

“It was weird sleeping on that stage after sleeping in small rooms (the family had recently been living in a small caravan) there was a real cold feeling of openness. Every noise had an echo and sounded very loud, even the slightest sniffing or scratching of the rats that came out at night could be heard easily.

Those Polish soldiers knew how to put on a good dance and party. Many nights I sat up in my bed on the stage watching the good fun and listening to the singing until I’d fall asleep. The song I seem to remember the most was one called `Lilli Marlene’, it is a lovely song and everyone used to join in, including myself after I’d learned most of the words. They were never rowdy and none of them ever failed to come up on the stage to give Val and I a sweet, or play a game with us if we were awake. I had a very happy fourth birthday while we lived on that stage.”

Getting hold of an empty hut was a real challenge as Elizabeth explains: “The Polish Officers had commanded guards patrol round to see no-one went into any huts that looked vacant, so all the moving had to be done between the ‘guard duty’ rounds, which made things a little daring and exciting, not to mention the crafty side of it. We really got very devious, chatting to the guards and offering hot cups of tea, with homemade cake, made with any ingredients that they had given us on the side. That was enough for them to turn a blind eye.

Sometime during the next few months my brother and his family moved into one of the long wooden huts in the Top camp. By this time we noticed the army personnel were gradually reducing in numbers. In our estimation there would be more huts becoming available. One of the male neighbours, whose name was Walter, came to me early one evening and told me to put a chair on my pram and follow him. We never seem to question any statement made like that. I was soon on the road with him to the Top camp where my brother had found an empty hut. ‘Quickness’ was the rule of the day and one had to get a piece of furniture, which in my case was a chair, into the hut before you could claim ‘Squatters Rights’ as we called it.

The neighbour went back with the pram to collect more of my things, while I sat quietly on the chair in the middle of the hut. Suddenly the door burst open and in walked a Polish officer with two of his men. Within minutes I found myself being picked up, still in the chair, and deposited outside in the road. They really had no right to do that, but once I was put outside, there wasn’t much I could do about it either. My luck wasn’t in that night.

I was visiting Frank a few weeks later, when we decided to take a quiet walk around, which was generally done late at night, to see if any other huts looked deserted. I had seen one previously next to his, which I thought looked a little deserted, so we investigated that first. There was only one bed in there, so we took the mattress to the furnace and put the iron bed outside, nailed up the windows, and locked the door. The next day I moved in.”

David tells the story of how another family, the Ramages, joined the camp: “A couple of days later Uncle Frank discovered another empty wooden hut. Baby-sitters were found and he picked the lock, moved some beds out and Auntie Joyce and Mum sat on some boxes behind the door to stop anyone else coming in. Uncle Frank hopped on his bike and rode down to their room in Old Amersham only to find that they were at the Regent Cinema in Amersham watching a film. Uncle Frank rode back up to the cinema and asked Mr. Carr, the manager, to flash a message on the screen. Mr. Carr said he could only do that in an emergency but when Uncle Frank explained the situation and he knowing the hard times some people were having just after the war, he agreed. The message was put up on the screen, Phyllis and Bob came out and things began to move quickly. They borrowed a van, loaded it up with all of their furniture and they were moved in the hut by midnight that same night.”

Elizabeth describes how tough that first winter was living in the wooden hut in the top camp with blankets for walls: “During one winter there was thick ice on the inside of the windows, but I still had to get the children up and take them to work with me, walking a couple of miles in the deep snow to earn enough money for milk, bread, and potatoes. I would carry Valerie as far as I could. David would come strolling leisurely behind, with me nagging him to ‘get a move on, or I would be late for work’. It seemed a long way to go just for two hours work for three shillings, but the journey was soon forgotten when we were settled back home, with a hot meal on the table. On the way home I would pick up wood from the hedgerows, although it was hard to find in the deep snow. On such days, not only did we have a meal – we also had warmth from the fire.

When the snow was very deep, we would take a spade to dig down below the snow, sometimes having to use our hands, which would be numb with cold. By the time we reach home the children would be crying with frozen hands and feet. They were good kids and always helped, and soon had smiles on their faces once more. While I was sawing the wood, they stacked it by the fireplace, then when we had the fire going and a hot meal on the table, all was well with the world once more.

On the odd occasion when I could afford a bag of coal or coke, I had to push the pram a couple of miles down to Chestnut Lane to collect it. This was quite a hassle with two small children hanging onto each side of the pram, or wanting to ride on top of the coal. I was never so happy to see the end of that first winter, but there were many more to come, and much worse, but through making a game of any situation, and being together, we survived. Being a deserted wife, it wasn’t easy bringing up two children on my own. At that stage there were no pensions or parent’s allowance, one had to work hard, otherwise starve. Although there was ‘The Relief’ one could go to, as a last resort, where we would be given a food voucher.”

David James’ memories of these awful winters show what an amazing job his mom did: “We spent a lot of time indoors due to the bad weather and there was always a lot of good things to do. Mum could tinkle a dozen tunes on an old piano we’d acquired from somewhere and she was good at reading books to us. We could also keep ourselves amused. For a long time I had a cocoa tin full of dried broad beans that I’d play with for hours. It was amazing what those beans could be or do. One game that Val and I loved was when Mum would hide some of the beans and the two of us would hunt until we’d found them all with Mum cheering for each one found. We used to play Hunt the Thimble. Mum would hide her thimble (it had to be the real thing) and then tell us if we were hot or cold, depending on how near or far away from the thimble we were in our search. The games were always played amid much laughter and squeals of delight. The winters always went as fast as the busy summers.”

The Beech Barn camp occupants became politicised and were part of a national campaign to get local councils and the government to take their plight seriously and solve the housing crisis. Jennifer Abeledo was told by her mother, Margaret Hartley that Margaret and John Hartley demonstrated on August 1946 with Jennifer in a pram when she was only 2 weeks old. A picture of the family at the protest made the front page of the national press and subsequently they were one of the first families to occupy a Nissen hut at the camp. Amersham Council eventually took over the organisation and renovation of the camp and the James family moved to one of the refurbished Nissen huts, now called 16 Beech Barn, Chesham Bois.

As David explains: “Compared to the wooden hut, our new hut was a palace. It had an inside toilet – there’d be no more going across to the ablution block on dark nights. It had a bath, and a copper to heat up the water, and there was a big kitchen range in the living room. It also had real walls, no more blankets hanging on string. Yes, this was luxury!”

David describes how the families furnished their homes with cast-off furniture and auction bargains and helped each other out “If somebody had any items that they couldn’t use, then those items would be given to somebody less fortunate. I saw many examples of other people’s generosity on that camp – a bed being carried over to this hut, an armchair being carried over to that hut, a wardrobe being carried over to another hut, etc. Even so, most of us families were still not up to the ‘bare-essentials’ stage at the time.” And the excitement of their ‘recycling’ the furniture from the empty Piper’s Wood camp “The news spread like wildfire as all the families were gathered and informed about the message. Soon there was a procession of women and children with carts, prams, trollies, pushchairs, and anything else with wheels, heading off towards Piper’s Wood. A few of the families already had enough furniture, but they took off with us to help other families bring something back. As the men arrived home from work and heard the news, they each took off to lend a hand. The Piper’s Wood camp was almost stripped bare of furniture before the night was through.”

The adults obviously worked incredibly hard to create secure homes and provide for their families. Elizabeth worked as an usherette at Amersham’s Regent Cinema as well as a waitress at Darvell’s Café in Amersham and as a cleaner for a local solicitor and a local doctor. Her mom, Annie Challis, was a cleaner at the cinema, her husband Bert was a boilerman at Latimer House and their son James, became a projectionist at the cinema when he left school. Elizabeth’s second husband Zygmunt Kissman, a Polish soldier, worked as a labourer and then a shoe repairer and her brother, Frank, was a woodworker in a furniture factory in Chesham. John Hartley was an electrical engineer and his wife Margaret worked at the telephone exchange as a telephonist – all whilst they lived in the Beech Barn camp.

The camp was supported by a local doctor: “Doctor Howell was our doctor and a wonderful friend to us children on the camp. We adored him and so did our mums. Not only was he a good sport and doctor, he was handsome with it. He owned a big, maroon Standard Vanguard car and, nearly every day he’d be up at the camp for someone or other. He always leaned cheerfully out of the car window to wave to us children if he saw us around. Doctor Howell’s surgery was situated at Oakfield Corner in Amersham, on the corner of Rectory Hill and Chesham Road”.

In addition to the shops in Chesham Bois and Amersham, “I loved the way each shop or counter had its own particular aroma. There would be the rich smell of coffee at the coffee grinder, the soft smell of chocolate at the sweet counter, the cold, thin smell of the meats, the sharp tang of the cheeses, the keen smell of shoe polish, the list could go on and on.” David remembers a mobile shop which came to the camp every week: “This van was loaded with all sorts of groceries and goodies. The driver used to move slowly around the track ringing a large hand bell outside the driver’s window to let his customers know he was there. Upon hearing the bell, we’d rush out and stop him and while Mum and Nan bought the groceries us children would stand looking at the toys and sweets until the van moved on.”

Despite the many hardships David describes an almost idyllic childhood for “an adventurous lad like me” and has many happy memories of those “golden days in the camp”. Alone, or with other children from the camp he would roam free in the local woods, playing cowboys and Indians in the dell in Howlets Wood, making secret camps, picking bluebells for his mom, going to fetes at Chesham sports ground (now the football club), sledging down the hill to Chesham, playing on the Moor, helping with the harvest at Channor’s farm (Mayhall Farm), climbing trees on the common “there probably wasn’t a climbable tree around the common that I didn’t climb”, fishing for newts and tadpoles in the pond, watching owls in the evening, “we used to have wonderful picnics on that common, lounging in the soft, springy grass with a sandwich in one hand and a glass of ‘Tizer’ in the other.”

Some adventures were more dangerous than others especially as there were still signs of the war everywhere: “We were forever finding empty bullet cases around that camp and one day, during that spring, David (a friend from the camp) and I found two rusty old mortar bombs with brass flights in the thick grass near our hut. We spent the next five minutes throwing them up into the air and watching them drop while we made the appropriate exploding noise with our mouths.

One of the camp men coming by said hello to us, then I saw his jaw sag and his eyes nearly pop out of his head as David threw his bomb into the air. Those bombs were heavy and we couldn’t throw them very high, but it was high enough to frighten this man and he dived for the ground taking me with him. I think he almost died anyway when he saw that I too, was clutching a mortar. Looking very pale and shocked, he sent us both home and the police and army were called in to dispose of our two `toys’. I never knew if they were `live’ or not.”

Carol-singing, parties, bonfires and other celebrations were regular occurences in the camp. In August 1952 the Lynton and Lynmouth floods disaster occurred. “We were hearing all about the sad things that the people who lived there were suffering, and Mum decided to try and do something to help. It wasn’t long before a group of us youngsters were dressed up in fancy clothes and knocking on the doors of the posh people’s homes down all the local roads asking for money. Now, all the posh people knew that we were from the camp, that we were relatively poor, and that we were usually the ones they helped by giving us toys and carol-singing money. We could have been using the flood victims’ problems to gain money for ourselves. But not one single person asked us any further questions after we’d quickly explained why we were at their door, and not one single person refused to give us a donation towards our cause. We went to every house down every road locally, and the only houses we missed were the ones where nobody was in. It was so wonderful to see the money piling up and our parents were so proud of the people and us youngsters. Needless to say, every single penny went to the Lynmouth funds, and we all received a nice write-up in the local paper.”

In 1953, Elizabeth, David and Valerie were finally given a council house in Weller Close, Amersham. Over the last couple of years the different occupants of Beech Barn had been scattered to different council houses in the area. The Hartleys were one of the first to move out to the new town of Hemel Hempstead in 1950, with the Challises moving to Bedford Close, Chenies, Uncle Frank to Briery Way, Amersham, the Barretts to Piggotts Orchard, Old Amersham, the Ridgeways to Weller Close and the Jardines to Weller Road. Other families had moved to other estates such as the Quill Hall Estate. The Jameses were one of the last families to leave the top camp which was demolished at the end of the year to make way for its redevelopment as the Leys.

“In the middle of that same week a letter dropped through our letter box and, when Mum opened it she jumped for joy, we’d been allocated a house in that very area where all our friends were. Little did I know of the adventures in store for myself as we prepared to move from the old tin hut at Beech Barn. I’d never see the hut again. I have such wonderfully happy memories of those golden days on the camp but, at that time, I was more interested in the new part of my life to come.”

References:

Elizabeth Barry

Nicolas Salmon and Clive Birch – Yesterday’s Town: Amersham

The Times

Jennifer Abeledo