Mr Kirby does not appear to have stayed very long: Benjamin Witty is the last schoolmaster who can be found in the directories, in 1864. What happened after that is unclear, but on 3 May 1866 JH Morten wrote to the BFSS begging them to send a master and pleading ‘we are absolutely in extremis’. The high turnover of masters may indicate that, with increasing numbers of children attending school in the years just before the 1870 Elementary Education Act, it was difficult to find and retain suitable teachers, especially perhaps for smaller schools which could not offer high salaries. Unlike several of his predecessors Benjamin Witty does not appear in the Meeting House records as a Baptist but had previously taught in a National School in Wandsworth.

The school was no longer listed anywhere in 1869. The Annual Reports peter out after 1860. The rooms, however, were much in use for meetings and concerts.

When and why did the schools close? That the numbers had built up so quickly, to 79 girls and 54 boys by 1843, demonstrates a real demand for the education they were offering. The 1846 report asserted that ‘the reputation of the schools is such, that children are regularly frequenting them from the neighbouring villages and from the town of Chesham.’ In 1860 the committee had a credit balance but was beginning to feel the need for renewed fundraising: ‘The treasurer has a balance of £3 9s 6d [3 pounds 9 shillings and sixpence] in hand. Death has, however, removed three of the original subscribers, among them Mr Weller, who was from the first a generous supporter of these institutions, so calculated to benefit the town, and who ever took a lively interest in their prosperity.’ This presumably refers to William Weller who died on 8 September 1859 leaving an estate valued at under £35,000.

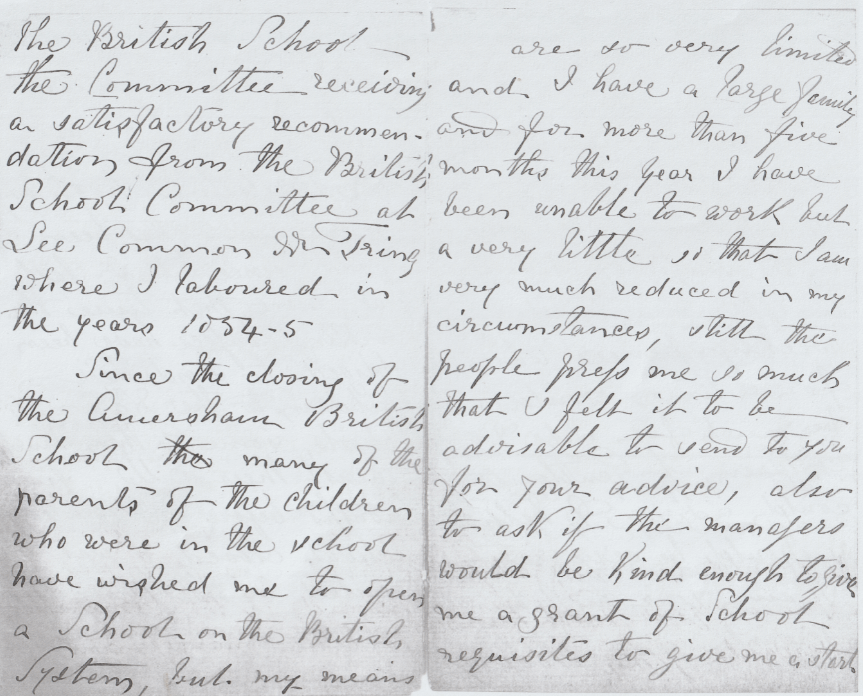

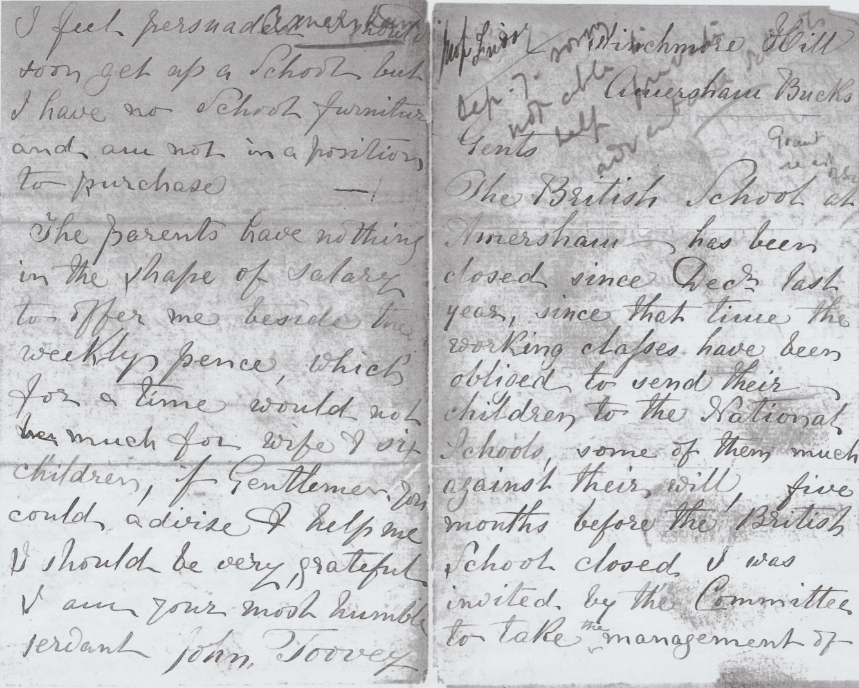

John Toovey (1829-1882) wrote a letter to the BFSS beginning ‘the British School at Amersham has been closed since Decr [December] last’. Infuriatingly the letter is undated and the annotation directing the clerk how to reply is dated only ‘Sep 7’! He relates how members of the working classes were obliged to send their children to the National Schools, ‘some of them much against their will’. Some of them have asked him to re-open the school. He had also been invited, five months before the school closed, to take on its management.

He had apparently been connected with, and could produce references from, the British Schools Committee at Lee Common ‘where I laboured in the years 1854-5’. He is now proposing to set up a new school on the British System, but has no funds to do so. The BFSS evidently turned him down as the letter is annotated ‘sorry not able to help private adventure schools.’ Written from Winchmore Hill the letter also reveals that health problems had prevented Toovey from doing very much to earn his living for over five months that year ‘so that I am very much reduced in my circumstances’. He mentions his wife and six children. While this may not have helped him in his appeal for financial backing, it is a useful clue as the birth of his sixth child, Elizabeth Julia Emma, was registered in the last quarter of 1866 and so the letter must have been written after her arrival.

In 1867 the chapel was closed for several months while alterations were carried out and reopened again in August. It seems logical that this building work would have taken place only after the closing of the school.[1] It might also have made the re-opening of the school in its former premises unlikely or impossible.

Taking one fragment of a clue with another, an argument can be made for the school having closed by December 1866. John Toovey’s attempt to get the BFSS to back him to open a school in different premises would then have been made in late August or early September 1867.

Two other factors may have been influential in the closing of the school. John Toovey’s letter shows that the local Committee had been trying to find someone to take on the management of the schools. No contribution from Amersham had made its way into the Annual Report of the BFSS after 1860. If a reason for this is sought we may recall that it was Ebenezer West who on 11 February 1841 had written the letter to Henry Dunn, Secretary of the BFSS, in the name of the provisional Committee who had just held a meeting at his house. West signed his letter as Secretary, making it seem likely that he would also be the author of the printed undated report which celebrated the opening of the boys’ school in November 1842. The style of certain passages of the printed report and some rhetorical outbursts in the annual reports up to 1860 are very similar, especially when urging education for the poor. Ebenezer West ran an extremely successful school, the Amersham Academy. This was a boarding school and therefore must have been patronised by parents able to afford such fees. It was also a very academic school and searching the British Newspaper Archive for ‘Amersham’ and ‘school’ produces little about Amersham but many entries concerning the awards and entry to universities won by Mr West’s scholars at Amersham Hall School, Caversham. In 1861 the school had moved away from Amersham in search of better premises. It may well be that at this point the Committee lost its efficient administrator and guiding light. Ebenezer West was a fervent advocate of education for all and had long experience of teaching and managing his own school. He was a staunch supporter of the BFSS and the Proceedings of an Educational Conference Held by the British and Foreign School Society on the 14th and 15th March 1844 (p 61) show that he donated £10 to the cause. The National Archives historic currency converter (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter) shows the equivalent in 2017 to be £604.17. With such a sum he could have alternatively bought himself a good cow or paid the wages of a skilled craftsman for 50 days.

If indeed he continued to serve the Committee from 1841 to 1861 as secretary they may well have found it almost impossible to replace him when he left.

The other factor is the change in attitudes to universal education. In 1841 the battles for the education of the poor and for non-denominational schooling were still being fought. The Protestant Dissenting Deputies, who lobbied on behalf of the Presbyterians, Independents [or Congregationalists] and the Baptists, were greatly in favour of education for its own sake. As the industrial revolution gathered pace and the population was also increasing rapidly, workers migrated from agricultural areas to expanding cities where, like other facilities, educational provision was inadequate.[2]

By the mid to late 1860s the balance of opinion had altered, the state had been providing some funding to both National and British schools and many people, including the Deputies, were beginning to doubt whether voluntary schools were capable of satisfying the increasing demands made upon them. It was more a question of when and how educational provision would be widened, with the involvement of the state, than of whether it would happen.

In one sense the British Schools had achieved many of their goals. Many existing schools would be transferred to the new local Boards once they were set up after the passing of the Elementary Education Act of 1870, under which schooling was to be available for all children between the ages of 5 and 12.

Robert Southey, who was by no means an admirer of Joseph Lancaster, suggested as early as 1812 that the achievement of the movement started by him, lay not just in what the BFSS schools accomplished, but in the galvanising effect those schools had on other educational providers, most notably the Church of England. Writing from Keswick to W W Wynn MP on 4 February 1812 he commented:

‘What we are obliged to Lancaster for is, for having been the means of frightening the bishops who (except for the Bishop of Durham, indeed) would never have exerted themselves if they had not been compelled to it.’[3]

The Post Office Directory for 1869 lists only three schools in Amersham — the Free Endowed Latin Grammar, the Free Endowed National School and an Infant School.

The Amersham Baptists may have put their trust in the idea that the state would shortly be organising education for all children, free of any religious bias. The secretary of the BFSS, addressing a meeting in Aylesbury, spoke of the ‘present excitement among the people for unsectarian and religious education of children, who wanted not a national school but a school for the nation’.[4]

A letter dated 27 August 1872 to R Saunders Esq from George Tottle, master of a Board School in High Wycombe, reveals what was being said about the closure: ‘I was informed that the late British School was closed on account of disagreement and a determination to compel a School Board to be formed.’[5]

Resistance to the idea of School Boards was, however, widespread, particularly on the grounds that it was an untried system and that paying for it would cause local rates to rise.[6] Meanwhile a shift in attitudes was taking place. The Deputies and many others, who in the 1840s had put their faith and energy into expanding the voluntary sector, now accepted that the voluntary schools could not provide education for all. In particular such schools would struggle to compete with those which did not charge fees.[7] Parents on tight budgets were doubly disadvantaged by losing their children’s earnings or help at home and by having to pay school fees which typically cost between a penny and twopence per child per week.

What in fact happened, a year after that letter, was that a new school was built in Amersham, large enough to accommodate 254 children with a separate infants’ department for 30. This was not a Board School but a National School, later to be called St Mary’s.[8] As it was a ‘Free Endowed’ school the implication is that fees were not charged.[9]

It may seem that in the end the Baptists had been outmanoeuvred and their hopes for any revival of the British Schools dashed, but for over 25 years they had been able to put their ideals into practice and provide an up to date education, leading to wider opportunities in life, for many of the neighbourhood’s children. This was no small achievement.

[1] Bucks Herald, 31 Aug 1867, p 6

[2] BL Manning, The Protestant Dissenting Deputies, 1952, p334-5.

[3] Selections from the Letters of Robert Southey, edited in four volumes by John Wood Warter, Vol 2, 1856, p250

[4] Bucks Herald 3 December 1870

[5] BFSS/1/7/2/9

[6] Pamela Horn, The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild, 1989, pp16-18

[7] BL Manning, The Protestant Dissenting Deputies, 1952, p349

[8] https://amershammuseum.org/history/old-town/school-lane/

[9] It was not until the Elementary Education Act of 1 May 1891 that the government made elementary schooling free