Madeline Agar (1874-1967)

Madeline Agar ran a horticultural business, Holly Bush Nursery, in Chesham Bois. Originally from London, she published books on garden design based on her travels and the gardens she had designed abroad including a garden in Cairo. She included a model of this in the Mid Bucks Suffrage Society’s exhibition of July 1914. She was probably converted to the suffrage cause when working for Frances Dove as a teacher at Wycombe Abbey.

During the war, the Mid Bucks Suffragists followed Millicent Fawcett’s instruction and stopped actively campaigning for the vote. Instead they put their administrative and fundraising skills to use for the war effort principally funding hospital beds and medical supplies. Many of our local suffragists had hospital beds and even whole wards named after them. The Common Cause of 21 September 1917 lists Catherine and Renée Courtauld as both donating £100 (over £8,000 today) to the Scottish Women’s Hospital Service.

Madeline Agar and the Hollybush Nursery

The founder of Amersham’s Hollybush Nursery, Madeline Agar was a ‘New Woman’, a pioneering, professional, female landscape architect and garden designer. She became a Fellow of the Institute of Landscape Architects, worked for the Metropolitan Parks and Gardens Association, and published several books. During WWI she was one of the founders of the Women’s Land Army and designed the Richardson Evans War Memorial on Wimbledon Common.

At the start of the 20th century, Madeline Agar moved to Amersham when she was in her early 30s and unmarried. She was probably familiar with the area having previously worked at Wycombe Abbey and was looking for a large site close to her work in London where she could establish a plant nursery and her own design practice.

Madeline was one of the first women to receive a formal horticultural training, and needing to earn her own living, she was looking for an opportunity to create an independent lifestyle. In Amersham she soon found a community of likeminded women and social reformers such as the Richardson sisters, the Colensos and Polly England. With Polly England she became a member of Catherine Courtauld’s Mid-Bucks Suffragists campaigning for Votes for Women.

Hollybush Nursery

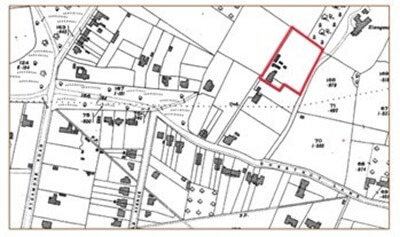

In the early 20th century Amersham was at the start of a housing boom following the arrival of the railway. Fashionable houses where beginning to sprout up around Chesham Bois and Amersham Common in large plots which all needed a suitably fashionable garden. Recognizing the opportunity, in 1906 Madeline purchased a house, then called Hollycroft, with land from Anna Springett Glazebrook, in Hollybush Lane just off Chestnut Lane on Amersham Common. The land was part of a larger field, Hollybush which had been a Manor Farm field and was close to the Elangeni estate and Chestnuts Farm. The site included a cottage for a nurseryman and Madeline appointed Frank Allaway, in his early 20s, who moved into the cottage with his wife Jennie.

Initially Madeline seems to have run the nursery with her friend, Miss G Holmes. This may have been Mary Georgina Holmes (1872-1916) born in Marsh Gibbon, Bucks who died in South Africa but a link has yet to be confirmed.

Advertisements in the local press informed readers that the nursery offered: “Gardens designed and laid out. Bulbs grown in fibre for transference to customers own bowls” and “undertakes special pruning jobs; and grows and supplies the best roses, herbaceous plants and shrubs”. Madeline also offered residential training to female students in horticulture.

Just before the start of WWI nurseryman Albert Henry Hall (1882-1947), from Hampshire, moved into the cottage with his wife Emily (1874-1958) and two young sons Charles Henry and Albert James (Jimmy). Albert took over running the nursery business in 1923 when Madeline moved to Milford-on-Sea, close to her family. He expanded the business into additional premises just off Sycamore Road in Woodside Close (possibly where the carpark is today?) with a florists and grocery store. He also grew flowers in a field beside the first St Michael’s Church where the current St Michael’s was built in 1966. After Albert’s death in 1947 the business was continued by his sons until the 1970s.

The original Hollybush Nursery site was sold to developers in the 1970s and redeveloped in the early 80s as residential housing, now Hollybush Lane.

Early Life

Madeline Agnes Agar was born in Notting Hill into the large prosperous family of Edward and Agnes Agar. Her father was a solicitor and later a manufacturer and had the then radical idea of educating his six daughters to the same level as his three sons. The family moved to Wimbledon where the girls could attend the recently founded Wimbledon High School (WHS) which provided an excellent education.

Although petite, Madeline was sporty like her father who is considered one of the founders of modern hockey. At WHS she played netball and tennis competitively. Her early love of gardening was nurtured at the school where there was a garden society and 15 garden plots for students. She was the librarian of the upper school and secretary of the Art Society. Madeline excelled at art, earning distinctions in her final exams in Drawing and Geology. Her love of Geology led to her being a keen collector of fossils. She was also an active member of the Debating Society which “helped her to develop in to a forthright and articulate woman”, according to academic Leanne Newman, who wrote about Madeline Agar in a 2020 article in the Garden Trust’s Garden History journal.

After leaving school in 1892, Madeline worked for a year as an assistant mistress at York High School, and it looked like she would follow her older sister Winifred to Newnham College Cambridge and become a teacher. Madeline however had other ideas and persuaded her parents to enrol her at Swanley Horticultural College in Kent for a two-year course.

Swanley Horticultural College

When Madeline joined the college in 1894, she was accompanied by another WHS pupil, Lorrie Dunington. There were 20 female students, even though women had only been accepted on the course since 1891, two years after the college was founded. At the time the gardening profession was almost all male and based on an apprentice system of horticultural training. Instead, the college offered scientific, engineering and surveying courses as well as practical classes in horticulture, dairy work and beekeeping. Lorrie Dunington became the first woman to be awarded the Diploma of Proficiency for Bee-keeping by the Bee-keepers’ Association and later became celebrated as a landscape architect in Canada and the USA. In 1893 the Royal Horticultural Society introduced a national qualification in Horticulture with a rigorous examination system. Social reformers insisted that gardening was a suitable career for women and pioneering doctor Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was recruited to Swanley’s council to ensure that the training at Swanley was not detrimental to women’s health. The recruitment campaign was so successful that by 1901 Swanley had become an exclusively female college.

Madeline’s parents were certainly reassured, and their support was vital as the annual cost for tuition, room, and board was £80, around twice the annual salary of a farm labourer at the time. The uniform list was also extensive including a coat and tunic of Swanley tweed, a blazer, blouses, jumper, brown felt hat, a straw hat, a Mackintosh, two pairs of boots, clogs or gumboots and a blue serge apron or a green tunic in summer. The women students lived in separate accommodation with a chaperone and a strict bedtime with lights out at 10.30pm. However, the women were allowed to ride bicycles in the college grounds!

Madeline maintained close contact with WHS and submitted regular letters to the WHS magazine. In one she described a typical day at the college as starting at 6am with watering, potting plants, milking the cows or feeding the chickens. Practical work ranged from “the roughest manual labour to the most delicate budding and grafting”. The female students must have worked extra hard to prove their right to be at the college as they excelled in the final RHS exams. Madeleine’s Swanley colleague, Annie Gulvin, achieved the highest mark in the entire country. Madeleine was also a Gold Medallist and won the prize for best student in Practical Horticulture. That year she was the only student at Swanley to obtain a first in Advanced Theoretical Chemistry.

Wycombe Abbey

After graduating from Swanley in 1896, Madeline found a job at the newly established Wycombe Abbey Girls School led by women’s campaigner, Dame Frances Dove. Here Madeline taught horticulture, gardening and flower arranging but also supervised the grounds and gardens. The school had just moved into Loakes Manor house which had been purchased from Lord Carrington. Madeline had a free hand at designing new beds and terraces with an undergardener to help with the manual labour. Becoming a head gardener at such a young age was an impossible dream for most of Swanley’s female graduates. By 1900 the gardens were well established with rose beds and extensive flower borders. Students had their own plots for planting seeds and growing sweet peas or soft fruit such as strawberries. Madeline’s experience at Wycombe Abbey inspired a later book, A Primer of School Gardening (1909) full of practical advice. The best way to dispatch an unwanted mole was a “blow on the snout” apparently!

Wycombe Abbey also developed Madeline’s interest in social reform as it aimed to provide the girls with a sense of public responsibility and public spirit. The school worked closely with the United Girls’ School Mission to support underprivileged children. Madeline was also clearly influenced by her headmistress’ keen interest in women’s suffrage and women’s rights.

Miss Dove had studied at Girton College Cambridge and in 1875, was one of the first two women to pass the Natural Sciences Tripos. However, it was not until 30 years later that she received her degree from Trinity College Dublin as one of the ‘steamboat ladies’ as Cambridge refused to award degrees to women until 1948. Around 1901 Miss Dove decided to join her former college principal, Emily Davies, in the suffrage campaign. She founded the Wycombe branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies and hosted Buckinghamshire’s first widely attended public suffrage meeting in 1904 at the school.

Landscape Architect

By this time, Madeline had left Wycombe Abbey as she hoped to take up a teaching position at Swanley College in 1903. When this didn’t materialise, she travelled to Dominica in the Caribbean where two of her brothers were working on a family plantation. She also travelled to America where she took courses in landscape architecture as these were not then available in Britain.

On her return to England, she started working on private commissions and established her busy practice in Amersham. In 1911, she published a second book, Garden Design in Theory and Practice which was reprinted many times and used as a text book at horticultural colleges.

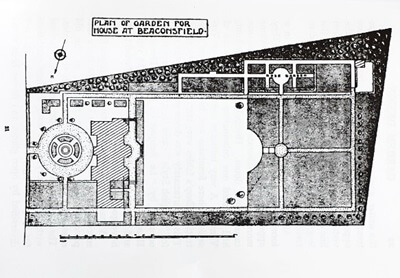

One of her first projects in Buckinghamshire (which featured in the book) was working with Charles Voysey to design a garden at Holly Mount, Knotty Green in 1906. She later worked with Voysey on a public garden in Kensal Town for the philanthropist Emslie John Horniman. Like her famous predecessor Gertrude Jekyll, Madeline worked with several Arts and Crafts architects and undoubtedly worked locally with John Harold Kennard.

Madeline’s style of landscape design was clearly influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and included natural features such as rough-hewn stone walls, sunken rock gardens, wildflower meadows, and water features. She also included formally planted borders and was passionate about roses, both in formal rose gardens and climbing profusely over pergolas. The archive at the Institute of Landscape Architects held at the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading includes Madeline’s handwritten note listing over 150 private landscape design projects. However, she was most proud of her designs for Place House in Fowey, Cornwall, Tusmore Park near Bicester in Oxfordshire and The Gables in Maadi outside Cairo. This project led to a lifetime friendship with the owner, Mary Stout and a jointly written book in 1921, A Book of Gardening for the Sub-tropics. The drawings and plans for the Cairo garden were included with some photos of Madeline’s other gardens in fundraising exhibitions held by the Mid-Bucks Suffragists.

Metropolitan Parks and Garden Association (MPGA)

Whilst Madeline was establishing her new business in Amersham, she was also working for the MPGA to transform disused inner-city churchyards into gardens and recreational spaces for the public and particularly poorer people with little access to green spaces. She started as an assistant to Fanny Wilkinson, considered to be the first professional woman landscape gardener in England, who became the principal at Swanley Horticultural College in 1902. In 1905 Madeline took over the role of principal landscape architect for the MPGA and designed over 40 gardens for them. These included gardens designed specifically for women at the St Pancras School for Mothers and St George’s Fields, Bayswater Road. Recognised as an expert in her field as an arboriculturist, Madeline advised local authorities on tree and shrub planting as part of town planning schemes, attended a parliamentary committee on the subject, lectured on the dangers of smoke pollution and ran training courses for local authority employees.

The Women’s Land Army

In addition to her suffrage activities, Madeline became an active member of the Women’s Horticultural International Union (later the Women’s Farm and Garden Union, WFGU) founded by Fanny Wilkinson. During WWI with many male agricultural workers away fighting and food shortages a problem, it was recognised that women were needed to take on key jobs in food production. After several failed attempts to get a co-ordinated approach off the ground, the WFCU met with Lord Selbourne, President of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries. They persuaded him to give them a grant of £150 to organise training for women farm workers. Under the new name, the National Land Service Corps, they launched an experimental 12-week course and by September 800 women had completed the training. Madeline became Honorary Treasurer and raised money to pay accommodation expenses for women attending training courses on farms in Essex and Northamptonshire.

In March 1917, Meriel Talbot a prominent figure in the WFGU announced that the National Land Service Corps was now the Women’s Land Army (WLA). Paid women officers were established in every county and a shorter four-week course was designed for volunteers who were registered, trained and placed in farms, market gardens and forestry estates. By the end of the war 18 months later, around 29,000 women had volunteered as ‘Land Girls’ to help with food production. Although this was a tiny percentage of the estimated 300,000 women who actually worked in food production throughout the war it was incredibly successful as a weapon in the propaganda war and vitally important in WWII when the WLA was reformed in 1938.

After the War

In 1918, Madeline finally took on a part-time lecturer role, teaching surveying and plan drawing, at Swanley Horticultural College. However, she left after two years, with several other teachers, over a dispute with the new principal. She continued to provide private lessons to some of the Swanley students, including Brenda Colvin, who became a nationally important landscape designer and was one of the co-founders of the professional body the Institute of Landscape Architects in 1929 and its first female president. Another of Madeline’s pupils, Sylvia Crowe served as President of the ILA from 1957-59.

Brenda Colvin also worked as her assistant when Madeline was commissioned to create a War Memorial whilst working for the Conservators of Wimbledon Common. The memorial, today Grade II listed, was unveiled in 1921 and includes the inscription ‘Nature provides the best memorial’. Madeline’s ambitious design centres around a tall granite cross, which she designed on a plinth inscribed with names of the fallen, set within an octagonal base of flowerbeds. Five rings of forest trees circle out from the cross intersected by wide paths in a five-acre circle of common land, now called the Richardson Evans Memorial Playing Fields, named for the benefactor who was instrumental in securing the land for the public. She also designed grounds for the Broadstone War Memorial in Dorset.

In 1923, Madeline moved away from Amersham to live close to her extended family in Milton-on-Sea. She served on the council of the newly founded Institute of Landscape Architects from 1931, becoming a Fellow in 1933 and continued to work for the MPGA, and on private commissions into the 1950s. In 1967, after a long, rich, fulfilling life and career Madeline Agar died in a nursing home in Milton-on-Sea at the grand age of 93.

Sources

Madeline Agar (1874-1967) From Lady Gardener to Landscape Architect published Gardens Trust publication/ journal Garden History Volume 48:2, 2020, Leanne Newman

An Almost Impossible Thing, the radical lives of Britain’s pioneering women gardeners, Fiona Davison

Burning to Get the Vote, the women’s suffrage movement in central Buckinghamshire, 1904-1914, Colin Cartwright

Garden Design in Theory and Practice (1911), Madeline Agar

Kelly Jones, Archivist Wimbledon High School

The archive of the Institute of Landscape Architects, Museum of English Rural Life

Remarkable women booklet (hextable-heritage.co.uk)

British Newspaper Archive

Ancestry