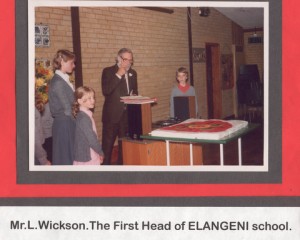

This article was written by Nick Gammage and is reproduced here with his permission. Most of the photos have been provided by Elangeni School.

The year of 2003 marked the 30th anniversary of the opening of Elangeni Middle School in Amersham. Elangeni holds a central place in the life of the town. Yet little is known locally of the remarkable family which built the house they called Elangeni on the plot where the school now stands, and from which it took its name.

With the help of documentary evidence, including the family’s copious correspondence held at Oxford University, it is possible to piece together that strange history. It is a story shot through with tragedy, controversy and heroism. The colourful cast of characters woven in to Elangeni’s history include an Anglican Bishop ex-communicated for heresy; an eminent Victorian scientist who camped out on the summit of Mont Blanc; a brilliant English lawyer who acted for the Zulu King Cetawayo; a dashing Prince killed by Zulus; a young Amersham engineer killed in a shooting accident in Russia; and a toddler killed in her crib by a bomb which exploded over Amersham during World War Two.

The Colenso family, which built Elangeni, moved on a world stage and unwittingly carved a permanent place in ecclesiastical and colonial history. Yet, with their house set back at the end of a long drive among woods and high hedges, much of this remained unknown to those living around them.

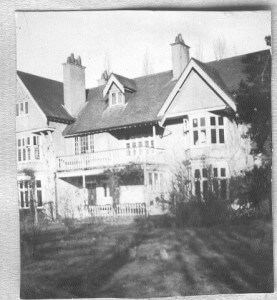

The house which came to be named Elangeni was built by London actuary Francis Colenso (known in the family as Frank) and his wife Sophie between 1901 and 1902. In 1900 Francis had bought two parcels of land, together amounting to around seven acres. One plot was bought from local farmer John Morten and the other from the trustees of Harry Scott (Harry and Sophie Belch, and Fanny Evans). The land was farmland on the edge of Chesham Bois common, stretching north from Chestnut Lane towards Blackwell Stubbs with stunning views over the Chess Valley. The Colensos were comfortably off, living in a large property in Cavendish Road West, St John’s Wood with a number of domestic servants. They bought the land at Amersham with the purpose of building a second home in the country.

They decided to call the house Elangeni – a Zulu word (and also the name of a Zulu tribe) meaning “where the sun shines through“. The choice of a Zulu word had a clear logic given the family history. Frank was the elder son of Bishop John Colenso, first Bishop of Natal and although born in Norwich, Frank spent much of his childhood at Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. The Bishop was a tireless supporter of the Zulu against what he saw as British colonial injustice towards native South Africans, His children all followed in his footsteps. They became close friends to the powerful Zulu King Cetawayo.

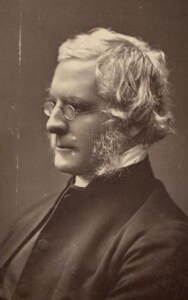

The Bishopric of Natal, a remote sparsely populated area of newly colonised South Africa, must have seemed to the Anglican leadership an unremarkable and almost anonymous see in the back of beyond. However Bishop Colenso, who went to South Africa in a missionary role to convert the natives, became one of the most controversial clergymen in the history of the Anglican Church.

Frank’s wife Sophie came from an equally well-known family. Her father was Sir Edward Frankland, one of the most notable characters of the 19th century who carried out pioneering work on valency. He was ambitious, tough, gifted and adventurous. In August 1859 he spent a night on the summit of Mont Blanc carrying out a scientific experiment. Frankland was knighted for his contribution to science, which included working as an advisor to the Government on the quality of drinking water in urban areas. He was one of the first examples of a professional scientist, and made a fortune.

Frank and Sophie’s courtship was, according to her sister Margaret’s diaries, very stormy. They had met at the Franklands’ London home; Frank was back in London from Natal studying for his law examinations. They became engaged in 1876, but after passing his exams he returned to Natal without Sophie. The distance put an inevitable strain on the relationship and she broke off the engagement in 1879. Frank was distraught. He came back to London and began pursuing her, turning up at her home and at her church but being rebutted by both Sophie and her angry father. Eventually, in May 1880 Frank got a job back in London. In May they were re-engaged and in November they married. Sir Edward Frankland died in 1899, leaving £140,000 in his will, distributed between the children of his two marriages in a way which split the family. It was the equivalent of many millions today. Sophie’s share was around £30,000. It is possible that some of the money used to buy the land on which Elangeni was built was from her father’s legacy.

Much of Frank and Sophie Colenso’s efforts were devoted to supporting the Zulu cause, and carrying on the Bishop’s work. In South Africa Bishop John Colenso is now thought of as a hero for his struggles on behalf of oppressed blacks. But back at England and in the eyes of the other South African Bishops, his unorthodox approach to missionary work wasn’t so well regarded. It reached the point where he was actually excommunicated from the Anglican Church. His story is extraordinary.

John Colenso was born in St Austell Cornwall in 1814. The Colensos could trace their Cornish roots back to the 16th century (when the name was probably Collynsowe). His mother died young and he grew up in poverty. He was, however, a brilliant mathematician and despite the family’s hardship he won a place at St John’s College, Cambridge. After graduating in 1836 with a good degree he took a place as a maths tutor at Harrow School.

The young schoolteacher borrowed money to buy a house, but tragedy struck when the house burned down. With debts of around £5,000 – a huge sum in those days – he was completely in the hands of his creditors. He went back to Cambridge where he could earn more through tutoring, and to earn extra began writing a series of algebra and arithmetic textbooks. These books became bestsellers in their day, and staple mathematics text books of the age. He sold the rights to his publishers, Longmans, and with the money paid off his debts. He was now free to choose his career.

In 1844 he was offered the position of rector at Forncett St Mary, in Norfolk, which was a living in the gift of his old Cambridge college. Two years later he married Sarah Bunyon, whom he had met at Cambridge where her brother was studying. Four of their five children were born at Forncett St Mary: Frances, Harriette, Frank, and Robert. The youngest, Agnes, was born in South Africa.

Colenso had been interested in becoming a missionary since hearing a sermon by Samuel Wilberforce. In 1853 he accepted the position of first Bishop of Natal – a remote, sparsely populated and dangerous province in South Africa. It was this appointment which was to change his life and make him a household name, but in the most unexpected way. When he arrived in South Africa, and began the task of converting the native Zulus, Colenso quickly came to the conclusion that he could not oppose the Zulu’s polygamy. He felt it would be inhumane to expect a Zulu warrior to desert all but one of his wives after conversion to Christianity, leaving the other wives and children without a husband and father. This stance caused uproar at home. But worse (in the eyes of the conservative church leaders) was to come.

Colenso, who was a brilliant academic, quickly mastered the Zulu language, produced the first Zulu-English dictionary and won the trust of the natives. He lived at Bishopstowe near Pietermaritzburg and worked closely with the Zulus, to convert and educate them. He was troubled by the questions they asked about the literal truth of the Old Testament – particularly the first five Books – for which he didn’t have answers. (How, they asked, could Noah have possibly fitted two of each animal into the ark?). Colenso concluded it was unsustainable to defend the literal truth of the Bible and said so in a series of hugely controversial books: “The Pentateuch and the book of Joshua Critically Examined.” The books sent the Church into a fury. He was put on trial for his views, and required to recant. He refused and appealed, arguing the South African bishops had acted beyond their authority. The appeal was upheld, but he was ex-communicated in 1866 by the South African Bishops. However he refused to accept the judgement, and despite being deprived of any financial support, continued to minister in Natal.

It must have been a remarkable upbringing for the Colenso children. Natal was an idyllic place to grow up, but supporting the native Zulus against the white colonialists made the family outcasts in certain quarters of white society, and must have brought hatred and suspicion on to their heads.

In 1862 at the height of the controversy the Colensos returned to England for three years. During this time the children were educated at a school in Lancashire run by a family friend. They returned to South Africa in 1865, Frank then went to Cambridge, entering his father’s college, St John’s, in 1869. He graduated in 1872.

After graduating from Cambridge, Frank Colenso returned to Natal. After passing his law exams in 1876 and becoming a barrister, he practised as an attorney in the Supreme Court of Natal from 1877-80, acting as chief legal advisor to King Cetawayo of the Zulus in numerous boundary disputes with the British Colonial rulers. The Zulu ways, and their language, were in the Colenso blood.

Frank Colenso’s influence over the powerful Zulu warrior King Cetawayo is well illustrated by a little known postscript to a notorious incident in the Zulu War of 1879, shortly after the humiliating British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwhana. This concerned the death of the Prince Imperial, son of the late Emperor Napoleon III of France who had fled to Britain in exile with his mother Princess Eugenie, under the protection of Queen Victoria. The Prince enlisted In the British Army and was shipped out to South Africa. He was killed when his scouting party was surprised by a group of Zulu warriors and he stumbled while trying to mount his horse to flee. His death was horrific: there were reports of his body being speared more than twenty times, including one stab through the eye as he tried to defend himself. Britain was in shock and his mother went out to see the scene of his death. In a letter to H H Clifford of July 1879, Bishop Colenso describes how his son Frank intervened on behalf of the family to inform King Cetawavo that this ambush victim was a European prince and request the return of his sword. Cetawayo duly returned the sword to Frank, who presented it to the Empress Eugenie.

Back in England in 1880, with his new wife Sophie, Frank took a job in Norwich as an actuary for Norwich Union Life Office, where he worked as Assistant Secretary and Assistant Actuary until 1886. His mother’s brother Charles Bunyon also worked for the company. Charles was editor of “Law of Life Insurance”. Frank became co-editor and then editor when his uncle died in 1892. In 1886 he moved to the English and Scottish Law Life Assurance Association in London. He then worked as an actuary at Eagle Life Assurance Company from 1899 until his death in 1910.

He was a distinguished actuary, an intellectual with the mathematical flair of his father. He wrote a number of learned articles for the Journal of the Institute of Actuaries (for example, the arcane-sounding: “On the application of Makeham’s modification of Gompertz’s expression for the law of mortality to the practical calculation of the values of survivorship benefits “). He served on the Institute of Actuaries Council from 1890 until his death in 1910, serving as Vice President from 1908.

In 1886, the family moved from Lower Close, Norwich to 21 Cavendish Road West, near St John’s Wood. The name of the road was changed in the 1930s to Cavendish Close. Frank and Sophie’s five children were all born during the 1880s. The first three were born while they were at Norwich (Esmond in 1881, Eothen in 1883, Irma in 1885). Sylvia was born in Marylebone in 1887 as was the youngest, Nigel, born in 1889. The oldest, Esmond, died within his first year at Reigate (the home of Sophie Colenso’s father, Sir Edward Frankland). Irma and the only-surviving son Nigel will make important re-appearances later in the story.

Bishop John Colenso died in Durban in June 1883; by then Frank was working for Norwich Union in Norwich. On 23rd June, in an article about the reaction to his death, the Times’ South African correspondent wrote (with typical Victorian understatement): “The comments of the Press are marked by a full appreciation of the personal and intellectual qualities of the deceased, coupled with becoming reserve upon the subject of his political action.” The town of Colenso, scene of a famous Boer War battle, was named after him.

Sophie’s father Sir Edward Frankland died on a salmon fishing holiday to Norway in 1899. The Colenso family correspondence in Rhodes House Library, Oxford, shows that Frank Colenso wrote thousands of letters to his wife Sophie during their marriage. They spent considerable periods apart: Sophie tended to spend the summer months with her children at Aldeburgh in Suffolk – not unusual at the time. She also made regular visits back to Germany (her father had studied under Bunsen at Marburg, and married a German wife) to see her mother’s family.

There is a moving, unmistakeable intimacy in that correspondence. It also gives us a fascinating insight into the planning and building of Elangeni. Trees and plants feature heavily in the plans for the new home. In August 1900 Frank writes: “We must have a nice group of shrubs, eventually a wood in the North East corner of our favourite field.” And later that month, as he sends her the plans, he writes: “Here are the plans again. The ‘House at Amersham’ certainly looks palatial, but then we have insisted on getting everything in.”

By April 1901 building work is well underway. He writes: “I expect the tiles will actually be on before the end of a fortnight as the carpentering of the roof is progressing urgently.” By now he is making regular visits. In May 1901 he writes to his wife, who is on a tour in the Rhineland: “I made a most propitious trip to Elangeni. I got to Rickmansworth at about 1 and enjoyed an excellent dinner there among the wallflowers. I turned up at the Glazebrooks [The Misses Glazebrooks lived in cottages on Chestnut Lane] at about 3. I got both the ladies to accompany me. The lawn is in excellent condition. The strawberries and canes show flower. There are two ladies in the village, the Misses Coles, who take in paying guests. £2.2.0d per week inclusive”.

There is then, in a letter of July 1901 to his wife at Aldeburgh, a moment which typifies the tone of the whole correspondence, and illustrates that this must have been a very close relationship between husband and wife. Frank writes from Elangeni: “The beauty of my surroundings is in every detail eloquent of you, sweet wife. The most gorgeous oleander blossoms are out. ”

Elangeni is being lived in by the Autumn of 1901. Sophie’s sister Margaret records happy visits to the new home in diary notes of September and October 1901. Workmen are still busy and the grounds are being planned. Her entry for 23 October 1901 is more evidence of the importance of music and trees at the home: “We walked to Elangeni (from the station) where we sat on the sunny verandah for some time, then had dinner in the dining room. In the afternoon I rested a little then we had tea and music in the drawing room. Sophie and I had planned out places for some young trees to be planted in.”

Elangeni is very much the second home of a prosperous London family. The Colensos retained their main home in St John’s Wood, and there is little evidence of them interacting with the local community. During that first decade of the 20th century Frank and Sophie Colenso continued to take a close interest in Zulu affairs. Frank published a number of articles in legal journals about what he saw as the injustices of court proceedings against prominent Zulus. His intimate knowledge of Zulu affairs proved invaluable to the government. Mrs Colenso and their daughter Sylvia joined with other campaigners in receiving delegations of native South Africans in London, and raising their areas of concern in Parliament.

Frank Colenso’s busy workload began to take its toll. In 1908, his health began to fail, and he died very suddenly in 1910 at the age of just 58. He was certified dead at Elangeni on 30th June by Dr. J. Gardner who recorded the cause of death as “pernicious anaemia, exhaustion and cardiac arrest.” There was a long obituary in The Times, on July 11, concentrating on his work supporting the Zulus. A notice in the Times on 6 July reported: “The Body of F. E. Colenso was cremated yesterday at Golders Green Crematorium. The Rev. R. J. Campbell officiated. The casket containing the ashes will be buried tomorrow at Reigate.” It may seem strange that he was cremated at Golders Green; however there is a simple explanation. Cremation was in its infancy in Britain, the first crematorium having opened just 20 years before. Golders Green was the second crematorium to open, in 1902. It was the nearest to Amersham. Reigate, where he was buried, was the location of the family home of his father in law, Sir Edward Frankland.

The obituary in the Bucks Examiner of 9 July reported: “Mr Colenso had been failing in health for some two years but it was only during recent weeks that serious symptoms developed.” The following year Sophie Colenso sold their home in St John’s Wood, redeemed the original mortgage of Elangeni for £1,500 and took out a new mortgage for £2,100 from the Public Trustees.

Two years later she was to suffer a further tragedy. Their only remaining son Nigel Colenso, born in 1889, was educated privately at Aldenham School, Elstree, from 1903 to 1907. He was an outstanding footballer and shot. He read Mechanics and Applied Sciences at Trinity College Cambridge and then worked as an engineering manager for the firm of Berwick Moreing and Co. at Ekaterinodar, South Russia. On April 11th 1913 he was killed by what his school magazine recorded as “accidental gunshot wound” at Apsheronskaya in Kuban Province. It was very unusual at that time for there to be an official notification and record of a death overseas. However his employers reported his death to the British consul at Batoum, and there is an official death certificate at the Public Records Office. He was just 23.

Sophie Colenso had now lost a husband and both sons, all prematurely, leaving three daughters: Eothen then aged 30 who had married Doctor Henry Young Cameron Taylor in 1911; Irma aged 28 and Sylvia 25. Sophie Colenso continued to live at Elangeni. Eothen’s husband died in the First World War in 1917, there were no children and she didn’t remarry. Sylvia and lrma married late: lrma married architect Angelo Crovo in Amersham in 1933. There were no children. Sylvia was an accomplished pianist, and accompanied the first recording of Nkosi Sikelel I Afrika (now the South African national anthem) in 1923. In 1938 she married socialist and pacifist Bertram Lloyd in Cardigan. Again there were no children.

Sophie Colenso died at Elangeni in 1937, aged 81. The death was certified by local GP Dr John Rolt who gave the cause of death as “lobar pneumonia”. There was a memorial service at Elangeni on the Sunday after she died, conducted by an old family friend, the Rev. Frank Dardis. The nature of Sophie Colenso is captured by a long and glowing front page obituary In the Bucks Examiner on 30th April, which calls Elangeni “the House in the Sun”. It records that “the cause that lay nearest to her heart was that of Peace”, that she had been a member of a number of Peace Societies, and that she was “an ardent lover of music”. It went on: “In the fields where the Colensos built their home they ‘composed’ in the true sense of the word a garden with the feeling of true artists.”

Art, as we’ll see, continued to be part of the essential spirit of Elangeni. The house, together with Holly Bush Cottage occupied by a William Fletcher, passed to her daughter Irma and Irma’s husband Angelo Crovo. In November 1938 the mortgage was paid off . Apart from these transactions, little has been known of life at Elangeni from 1938 until the house was sold. The big house was set well back from Chestnut Lane at the end of a long drive. The grounds were richly wooded, and the plot was surrounded by thick hedges. As a result, the house could not be seen either from Chestnut Lane, or from the cul-de-sac, Woodside Avenue, which ended at the Western perimeter of the grounds.

However an important insight into the nature of the Crovos and life at Elangeni can be gained from the account of Angela Hanbury-Sparrow. She lived briefly at Elangeni in the 1940s as a toddler with her adoptive parents, Lt. Col. Alan Hanbury-Sparrow and his German-born wife, Amelie, and was a regular visitor there when her adoptive parents returned to Amersham from Germany in the 1950s, buying a house in Hollybush Lane.

Lt. Col. Hanbury-Sparrow and his wife were living in Chestnut Lane on the night in April 1944 when a flying bomb exploded over Amersham near the Junction of Chestnut Lane and Hollybush Lane. Mrs. Hanbury-Sparrow was in the kitchen. When she checked on their 18 month old daughter Cristina, who was in her crib, she discovered that the little girl had been killed by the blast. The present owner of Springfields in Chestnut Lane, Tony Simpson, still has remnants of that bomb which landed in the garden and have been passed from owner to owner. The Crovos took the grieving family in, to live at Elangeni. Amelie Hanbury-Sparrow also lost a 19 year old daughter Gisela in the Dresden fire bombings. The Hanbury-Sparrows attended SL Leonard’s Church in Chesham Bois. They bought a tenor bell for the church and dedicated it to both daughters.

Lt Col Hanbury-Sparrow had been decorated for bravery in the First World War. He came from an old Shropshire family and served in the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He also lost a young daughter from his first marriage who fell victim to a hit and run driver. Following these tragic losses, the Hanbury-Sparrows decided to adopt. They adopted Angela and her twin brother (born in November 1944) in 1945 while the adoptive parents were still living at Elangeni.

Lt. Col. Hanbury-Sparrow was posted to Dusseldorf in charge of Agriculture at the British High Commission. His wife and their young adopted children joined him the following year. They returned to Amersham six years later, where they bought ‘Mansfield’ in Hollybush Lane. Angela remembers her adoptive father writing a play for a local theatre group, in which they all acted. They remained close friends of the Crovos, and regularly visited Elangeni. Angela Hanburv-Sparrow, who emigrated to Australia in 1967, remembers the Crovos as kind, “spiritual” people. “I remember the trees in the garden. There was a very large Quince tree. We used to sit under it in Summer. The house was always full of children but I remember my mother telling me that never had children of their own. There was always music from the old gramophone, and singing and laughter. It was a warm house with lots of love, kindness, compassion and healing from the Crovos.”

In their “spirituality” the Crovos had an affinity with the Hanbury-Sparrows who were Anthroposophists – members of the spiritual movement founded by Rudolf Steiner in the 1920s. She recalls Mr Angelo Crovo as being a kindly artistic man. “There was a smell of oil painting and I remember open doors, brushes and easels.” She recalls visiting the house as a young girl, and Mr. Crovo making her cashew nut sandwiches with cashew nut butter, honey and vanilla essence. She also remembers the vegetable garden, where the Crovos grew their own spices and herbs. In 1956 the Crovos sold four plots of land with a 240 ft. frontage on Chestnut Lane to Harrow builder, George Cox, for the building of four bungalows. Irma died in 1959, and in 1967 Angelo Crovo sold the house and land to Buckinghamshire County Council. Angelo retired to St Peter Port, Guernsey.

In April 1972 work began on demolishing the house and in September 1973 Elangeni School opened. The opening was delayed for two weeks into to the Autumn term as a result of late-running building works. Many of the trees at Elangeni were lost when the house was demolished, but a number survive.

In April 1972 work began on demolishing the house and in September 1973 Elangeni School opened. The opening was delayed for two weeks into to the Autumn term as a result of late-running building works. Many of the trees at Elangeni were lost when the house was demolished, but a number survive.

It is easy to imagine that a family which espoused the cause of supporting native Zulus against the British may not have been too popular, or considered socially acceptable in late Victorian and Edwardian England. However, it is clear from the personal accounts and other evidence that the Colensos, and the Crovos after them, had very special natures and were highly respected by those who knew them. That reputation for high standards and integrity has been carried on by the school which now carries the name of that remarkable house – Elangeni.

Elangeni – “Where the Sun shines through”